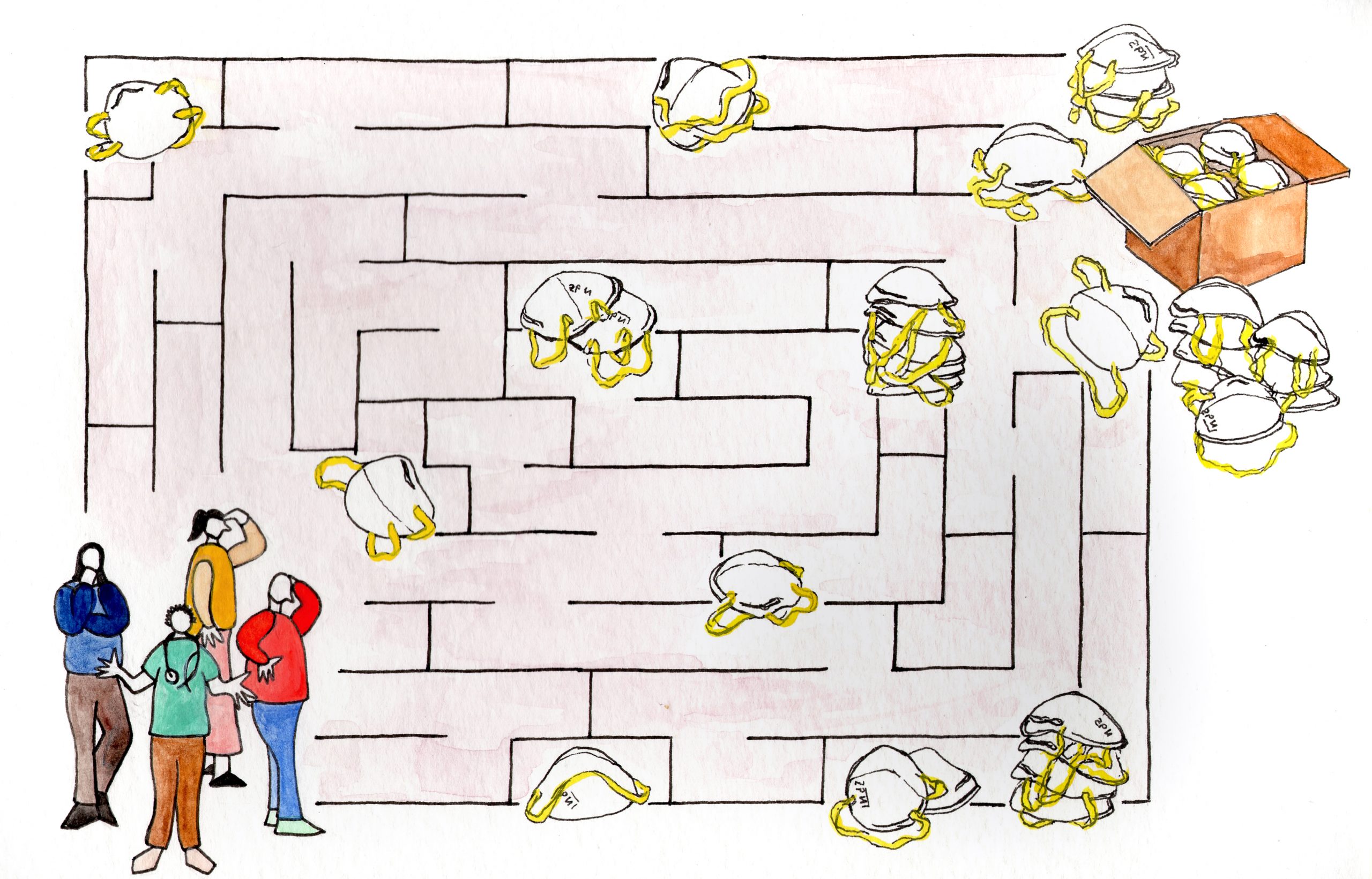

N95s, highly-protective masks that filter out at least 95 percent of airborne viral particles, are some of the most coveted products in the world. One year into the global COVID-19 pandemic, their allocation has been bungled in nearly every way possible.

As the months have gone by, the number of available N95s has soared, and yet the US government has neither publicized the new mask companies nor directed the increasing supplies to where they are most needed. A lack of knowledge and trust in these companies has led hospitals to severely ration their workers’ N95s rather than purchase additional supplies. The private market is no better: Facebook, Amazon, and Google are largely blocking domestic N95 manufacturers from advertising and selling their products. At the same time, most consumers feel obliged to use less-protective cloth or surgical masks due to continuing CDC guidance to reserve N95s for hospitals that will not even accept them. The CDC defends this policy by pointing to the relative efficacy of cloth masks and citing “reasons supported by science, comfort, costs, and practicality,” though these reasons seem increasingly outdated. So, the pandemic continues, millions of Americans live in fear of getting sick, and all the while tens of millions of life-saving products are sitting unused in storage facilities. The N95 shortage is an illusion, and as the virus and its variants continue to spread, more must be done to disseminate the essential products throughout the population.

The panic over N95 mask shortages was justified in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. In April 2020, Premier, a company that supplies thousands of US hospitals with medical equipment, reported that its member hospitals with active COVID-19 patients had an average of just three days’ worth of N95s in storage. To rectify this shortage, the US originally sought to import masks from abroad. Between March and September 2020, the number of imported shipping containers filled with N95s rose from six to nearly 3,000. However, US officials were wary of relying to such an extent on foreign countries, so the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) approved 19 domestic manufacturers to begin to produce N95s. In the subsequent months, these companies invested millions of dollars to expand their staff and equipment, until their combined capacity swelled to about 100 million N95 masks per month.

Incomprehensibly, the expansion of supply was not followed by increased use of the better masks, as NIOSH failed both to promote the manufacturers to the public and to disseminate information about how the masks were to be allocated. Internal emails unearthed by the Associated Press revealed that various high ranking officials, including Dr. John Howard, the head of NIOSH, were aware of the problem. According to the AP, Howard vaguely cited “the perception of inequitable treatment” and “the dynamic production landscape” as reasons for NIOSH’s choice not to publicize the new mask producers. At the same time, Howard referred to a published list of the domestic N95 manufacturers as a potential solution to buyers’ lack of awareness — but as the AP found, the list only “shows up on page 3 of an obscure newsletter published by a University of Cincinnati toxicologist, after a satirical column on ‘chin warmers,’ or improperly worn surgical masks.”

Further hurdles exist for hospitals attempting to purchase N95 masks. Given that many N95 mask manufacturers are new to the market, some hospitals are reluctant to place their trust in them — and the federal government has done little to verify their reputability. Additionally, from a financial standpoint, many federally-approved domestic mask manufacturers charge more for their masks than do international companies, so hospitals reject them on those grounds. Even a company like United States Mask, which sells N95s at just a few cents more than China, has had difficulty finding buyers in the health care sector. Finally, adding new brands of masks to hospitals’ inventories requires that all employees are fit-tested, a time-consuming process that dissuades many hospitals from signing with a new manufacturer. So, the root of the problem is not the unavailability of N95s, but rather the plethora of poor decisions that have kept the respirators out of the hands of those who need them most.

NIOSH has promised it will work to rectify the N95 supply problem by collaborating with federal agencies, as well as with Amazon. But Amazon, along with Facebook and Google, have made it very difficult for mask manufacturers to advertise or sell N95s on their platforms. Amazon not only periodically prevents customers from buying N95s, particularly those from smaller companies, but it also buries N95 products beneath dozens of less-effective KN95 masks for seemingly no logical reason. Facebook and Google simply block advertisements for medical-grade masks altogether. The platforms explain their policies by citing CDC guidelines about prioritizing health care workers, but as mentioned, many hospitals are not even willing to accept these manufacturers’ N95s. This creates a baffling scenario in which, in the middle of a global pandemic, dozens of mask companies are physically unable to sell their N95s. Having spent huge amounts of money to import or produce these products, the companies are now facing exorbitant losses. Protective Health Gear, for example, has 500,000 unsold masks sitting in storage. DemeTech, a family-run business in Miami, has 30 million.

Facebook, Google, and Amazon’s policies also spring from an effort to prevent the sale of counterfeit masks. This explanation holds some ground, as counterfeiters have been fairly prevalent in the mask market. But the presence of counterfeiters is no reason to restrict the sale of the masks writ large; rather, these companies and the government should dedicate resources to identifying and eliminating the fake products while aggressively promoting the real ones. One possible tactic involves the legal system; 3M and Amazon have collaborated on a lawsuit against a series of counterfeiters, and 3M also has a website detailing methods to combat respirator fraud. Rather than ignoring this resource and limiting the sale of N95s, Big Tech companies and the government must work to incorporate this information into a public education campaign to better inform people about how to buy legitimate products. Restricting the sale of supplies that could very well save consumers’ lives is not just illogical, but immoral — particularly given the fact that these platforms do nothing to prevent companies from selling nonmedical-grade supplies like bandannas and neck gaiters that actually make the spread of COVID-19 more likely. Unfortunately, according to The New York Times, “Facebook, Google and Amazon said they had no immediate plans to revise their policies.”

Despite the percentage of vaccinated people in the United States growing daily, the threat of COVID-19 persists, particularly with the spread of more-infectious variants. The US government, along with influential companies like Amazon and Google, must fix its broken dissemination process and initiate widespread efforts to get medical-grade masks to as many people as possible. President Biden recently invoked the Defense Protection Act to speed up the supply of vaccines and N95 masks, but there is still more to be done to relieve perceived mask shortages in hospitals, as well as to allow the general public to more easily access the respirators. Some have proposed a National Hi-Fi Mask Initiative in which every month, medical grade masks are mailed to each US household. This program was already implemented in South Korea, a country heralded as a COVID-19 success story, in the beginning stages of the pandemic. Furthermore, it is likely that the cost of the initiative would be negligible relative to the damage the virus has and will continue to inflict on the economy as the pandemic goes on. Overall, a program like this would not only enhance the safety of workspaces where employees are not yet vaccinated, but it would also help prepare the country for a future crisis of this nature.

As of now, we are falling victim to entirely avoidable problems, sprung from bureaucratic mismanagement and Big Tech monopolies. When the world shut down in March 2020, an extraordinarily successful effort commenced to expand N95 production capabilities in the United States. But it failed at its most crucial point, and after one year of turmoil, uncertainty, and loss, fixing the broken dissemination process for these life-saving supplies must be a top priority.

Photo: Original Illustration by Naya Lee Chang