Just nine days after surviving domestic abuse so severe that she went into premature labor, Marissa Alexander was arrested and sentenced to 20 years in prison. Her offense? Firing a single warning shot into the ceiling during a confrontation with her abusive husband, against whom Alexander had an active restraining order. No one was injured by her shot, and Alexander herself had no criminal record. Despite her claim that she was in compliance with Florida’s “Stand-Your-Ground” laws, which allow for the use of lethal force in cases of self-defense, it took only minutes for a jury to convict her of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.

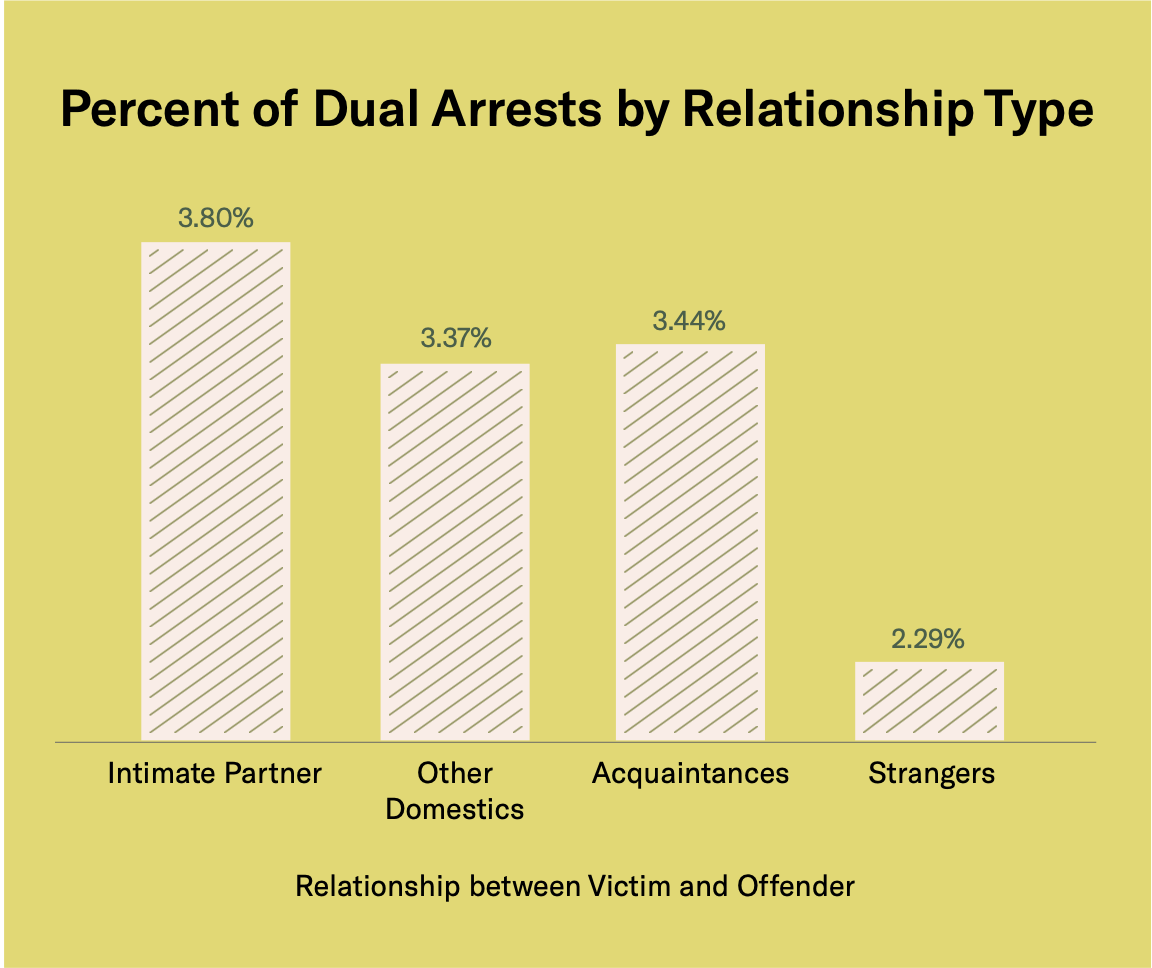

Alexander, like 7 percent of all domestic violence survivors, was the target of a dual arrest, a deleterious practice in which both the victim and the abuser are arrested. Dual arrests force women to choose between personal safety and a potential arrest, a major problem given the severity of the domestic violence epidemic. To put Alexander’s story into perspective, one in four American women will be the victim of domestic violence during her life. On any given day, more than 20,000 calls are made to domestic violence hotlines. Yet, only around 54 percent of domestic violence cases are reported. Although the reasons for choosing not to report domestic violence vary, dual arrest laws have a deterrent effect on women reporting domestic abuse. While laws that mandate the arrest of the primary abuser serve as an important and effective stopgap measure to address the prevalence of dual arrests, greater institutional reforms are needed to ensure that women can safely report domestic violence without personal repercussions.

The practice of arresting domestic violence victims is the direct result of 1970s-era mandatory arrest laws, which require police officers to arrest anyone suspected of perpetrating physical violence. These laws gave rise to dual arrests, as police officers were granted a legal basis to arrest women for physically defending themselves against intimate partner violence. By requiring that domestic violence cases be adjudicated in a legal system that has systematically disadvantaged poor and minority women, mandatory arrest laws, which purported to increase female safety, ultimately reinforced a system that disempowers many of society’s most vulnerable.

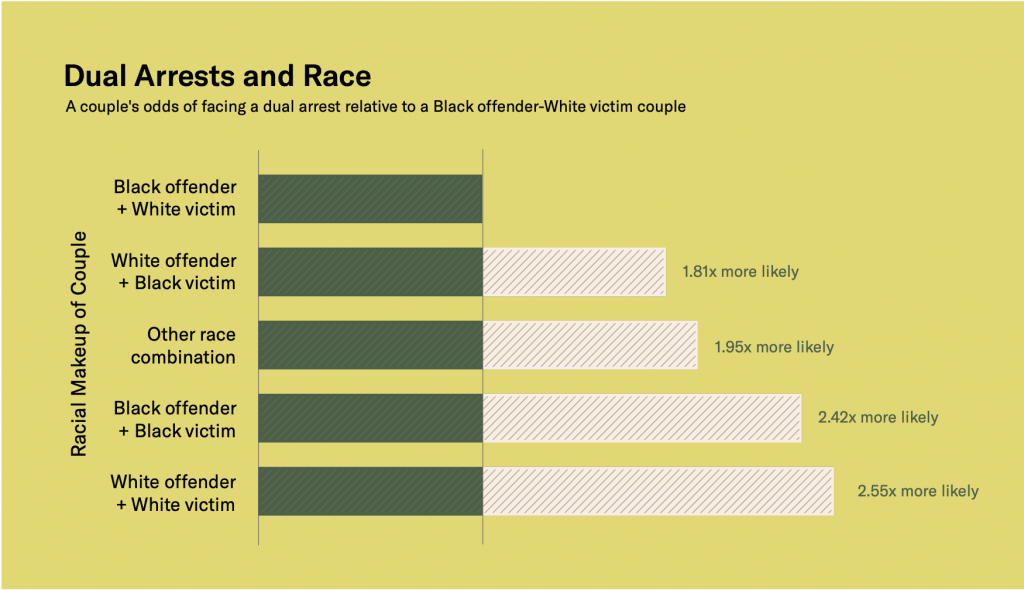

In the United States, BIPOC women often do not receive the same treatment as white women when they report domestic violence. Racist tropes that conflate skin color with aggression reinforce biases among police officers, causing Black women to be arrested alongside their abuser far more frequently than white women. Once arrested, Black women are also convicted at much higher rates than white women, often by juries that lack adequate racial representation. Dual arrests must be considered both a gender and racial justice issue, given their disproportionate impact on minority women.

Moreover, dual arrests often lead to financial penalties, eviction, and loss of parental custody, which have profound impacts on women and their families. These problems are even more dire for undocumented residents of the United States, for whom a family violence arrest record can lead to immediate deportation. These consequences only exacerbate the heartbreaking physical and mental health outcomes domestic abuse victims already face, including increased rates of HIV, depression, and suicide. Enduring domestic violence also increases the likelihood that a victim will face a host of chronic diseases, infertility, and drug and alcohol addiction, all of which in turn increase the likelihood of a future arrest.

Dominant aggressor laws have served as one effective solution to decrease rates of dual arrests. Also known as primary aggressor laws, these policies require responding officers to arrest the person who is deemed to pose the most serious threat in a violent encounter. Currently, 27 states have dominant aggressor laws. Considering the fact that dual arrests are twice as likely to occur in states without dominant aggressor laws, all states must move to adopt these policies. After Connecticut adopted dominant aggressor laws in 2019, the state’s dual arrest rate fell by between 7 and 11 percentage points from a staggering rate of over 20 percent. Yet, despite the efficacy of these laws in preventing dual arrests, they must be seen as a temporary measure in the struggle to prevent domestic violence. Many additional reforms, ranging from more stringent gun control laws to funding for emergency shelters and crisis hotlines, are also necessary to protect women from domestic violence and to promote reporting when abuse does occur.

The deep connection between police officers themselves and the perpetration of intimate partner violence only further complicates the fight to end domestic violence. Although data on officer-involved domestic violence is hard to acquire, studies have found that 40 percent of police families have dealt with domestic violence. This number stands in stark contrast to the 10 percent of non-police families that report domestic violence. Although national campaigns to send social workers and mental health professionals—rather than police—to domestic abuse calls seem promising, the solution is not nearly that simple. Domestic violence reports are the single most lethal call to which a police officer responds, due to the prevalence of armed and indiscriminately aggressive abusers. Until the United States reckons with the scourge of gun violence, replacing police officers with social workers will undoubtedly lead to civilian deaths.

Domestic violence is an extremely complex and personal issue that requires tactful and victim-centered policy solutions. Policymakers must prioritize putting an end to the practice of arresting domestic violence victims alongside their abusers. Dual arrests threaten women’s safety by discouraging reporting and placing marginalized groups at a heightened risk of interacting with a racist criminal justice system. While dominant aggressor laws serve as a critical stopgap measure for preventing dual arrests, larger institutional reforms are needed to increase reporting and promote women’s health, safety, and security.

After dealing with abuse and threats I called the police because I was being threatened. My abuser told the police I slapped him and I was arrested. Facing my job loss, now a record and the loss of my kids I can’t call the police. The DA did not prosecute my case. The abuse has worsened and I am threatened with jail again. I can’t make the abuse stop

The police can’t help me

Hey! This is a great article, but it would be more useful for research / advocacy purposes if you included citations. I can’t use this information to advocate for domestic violence victims without it.