The environment deserves legal rights.

On April 26, 2021, a wetland, two marshes, and two creeks sued a property developer in Orange County, Florida. The lawsuit, which sounds like the opening line of a bad joke, has significant import in the fight against climate change: It is the first ever test of the Rights of Nature legal doctrine. If upheld, the doctrine could set a major precedent for future environmental conservation lawsuits and greatly impact environmentalists’ fight against climate change.

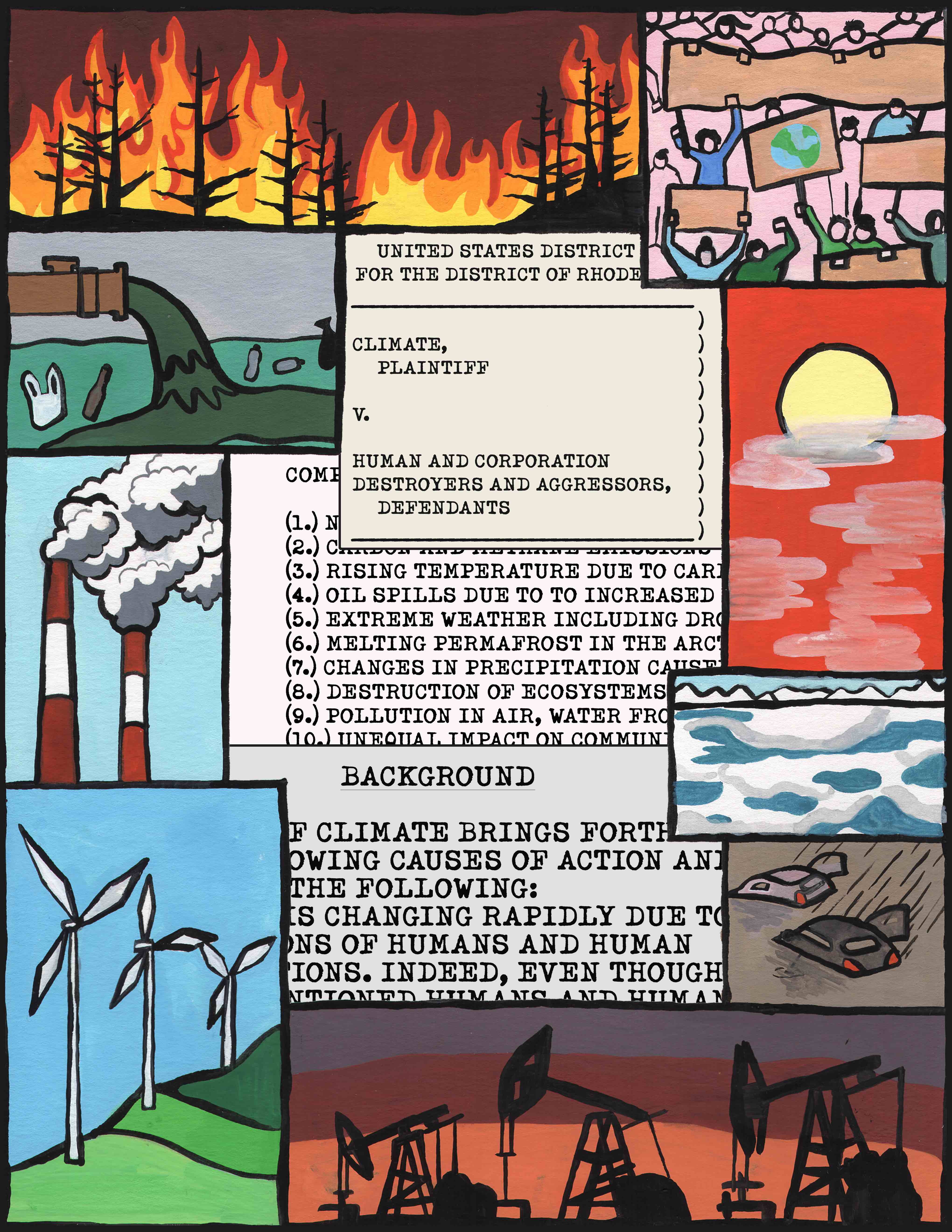

The doctrine seeks to bestow legal status of personhood upon the environment. It establishes that fixtures of nature—rivers, streams, and the like—are not objects to be owned but living beings with an innate right to survive and flourish. The Rights of Nature movement stands to shift the way society thinks about climate change: In lieu of a human injury being necessary for nature to be protected under the law, the doctrine provides a legal avenue for nature to protect itself.

The challenge inhibiting many environmental lawsuits is that of legal standing. Standing requires the individual or entity bringing the lawsuit to demonstrate that they have been directly harmed by the defendant and that the court has the ability to provide remedy for that harm. Since the harms caused by environmental degradation are typically difficult to ascribe to a single person or community, lawsuits seeking to protect nature from damages are often thrown out due to lack of standing. That is, those bringing the lawsuit are frequently unable to prove that they were personally and directly injured by the environmental harm.

Perhaps the most notable environmental case involving a question of standing was Sierra Club v. Morton, a 1972 lawsuit brought by an environmental advocacy nonprofit against Rogers C. B. Morton, the US Secretary of the Interior. The Sierra Club sued to stop a bid by Walt Disney Productions to build a ski resort on undeveloped land in California’s Sequoia National Forest. The case went to the Supreme Court, where, rather than rule on the merits of the case, the Court took up the question of standing, opening up debate over whether the Sierra Club would be directly harmed by the development of the ski resort. In a four to three decision, the Court sided with Morton, finding that the Sierra Club did not have the right to bring the suit. In their decision, the Court set the precedent that simply holding general interest in a problem does not constitute sufficient grounds to sue. This decision posed a major setback for environmentalists seeking to protect nature in court.

The Sierra Club’s lawsuit has attained status as a preeminent example of the legal system’s failure to serve environmental interests. Since then, proving standing in an environmental conservation lawsuit has repeatedly been an obstacle to legal protection. Often, it is the environmental fixture that would be damaged, not any specific human. And, while the loss of nature’s intrinsic value is devastating, the Court’s decision means there is rarely legal recourse for those looking to protect the environment. The Rights of Nature doctrine could fix that.

In his seminal 1972 writing, “Should Trees Have Standing? Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects,” Christopher D. Stone introduced the idea that the Rights of Nature doctrine would endow nature with legal personhood. Through the doctrine, fixtures of nature would gain rights typically conferred exclusively to humans. While it may seem outlandish, the theory has a decades-long legal history, having been referenced by Justice William Douglas in his dissenting opinion in Sierra Club, wherein he argued for granting legal personhood to nature.

The legal theory is premised on the idea that if environmental fixtures have a right to personhood, they cannot be owned or damaged. It combats an inherently Western notion of land proprietorship that allows an individual to acquire and subsequently destroy the aesthetics of nature. The view forwarded by the Rights of Nature doctrine—that nature is an individual with rights—has long been championed by Indigenous communities. Although the concept seems implausible, several nations and US counties have enacted similar provisions. The first community to grant nature the right to protection was Tamaqua Borough, Pennsylvania in an effort to prevent water quality damage from toxic waste. Bolivia, Ecuador, New Zealand, and India, as well as Toledo, Ohio, are among the other places that have bestowed personhood upon various parts of nature.

The aforementioned 2021 case against the Orange County developer serves as a bellwether for the doctrine’s legal viability. The lawsuit brought by the waterways alleges that if the developer dredges and fills 115 acres of wetlands, they would be in violation of a voter-approved charter amendment that grants waterways the right to “exist, flow, be protected against pollution and maintain a healthy ecosystem.” The charter received nearly 90 percent of votes from Orange County residents, an astounding win for a relatively untested concept. If upheld in court, the law could put an end to the Meridian Parks Remainder Project, which proposes a 1900-acre mixed-use development on an existing wetland marsh. However, despite its broad popularity, the Rights of Nature doctrine faces a significant uphill battle in court.

Yet the doctrine’s concepts are not entirely novel: Its treatment of natural fixtures is actually quite similar to the current status of business corporations in federal courts. In 2010, the Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United v. FEC that regarding political donations, corporations constitute legal persons, guaranteeing businesses full First Amendment rights. The impetus behind corporate personhood was, in part, to bestow legal privileges to a business that could outlast the lifespan of any one person—a quality that likewise applies to nature. The legal history of corporate personhood may provide both a roadmap and justification for Rights of Nature, despite the conflicting intentions of the two movements. Why should industry have undue influence within the legal system when the very land exploited under capitalism has none?

The Rights of Nature doctrine is certainly not free from criticism. For one, it threatens to create a liability for farmers and those dependent on agriculture who cannot guarantee zero fertilizer runoff. It also establishes a murky delineation between legal and illicit human activity, begetting criticism that the theory opens the door for a host of tenuous lawsuits. Furthermore, Indigenous communities have long championed a conceptualization of nature as a living being with rights, and the Rights of Nature doctrine risks casting that Indigenous belief of nature into a capitalist mold. Despite these vulnerabilities, granting nature standing to sue is the best legal method currently available to promote environmental conservation.

As climate change accelerates and leaves behind irreparable damage, it is imperative that we explore every avenue of protection. Although thus far untested in American courts, the presence of the Rights of Nature doctrine in legal discourse and its undeniable parallels to corporate personhood demonstrate the doctrine’s potential for success. The Rights of Nature doctrine offers a robust solution to the problems of climate change, one that will transform the legal system into a tool for positive progress and allow conservationists to fight for long-term protections for society’s most precious resources.