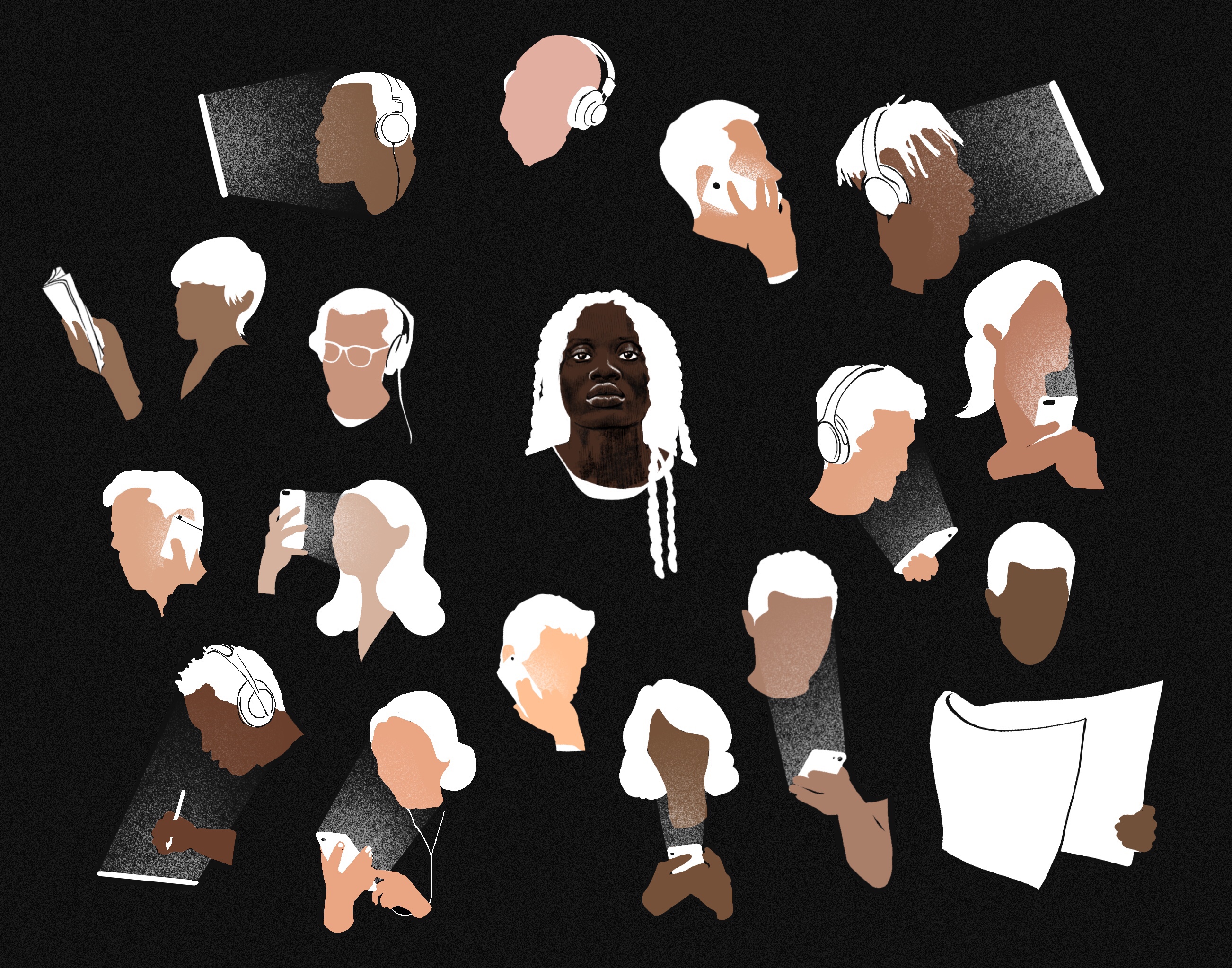

When you open your phone to send a GIF, what image surfaces in your mind? What media best encapsulates your feelings? For many people, the answer involves images of Black people. GIFs such as sipping with Wendy, the Nick Young Reaction, the Think About It Reaction, or the ‘Angry New York GIF’ are all extremely popular ways for non-Black people to share their emotions.

The idea that Black people are inherently more “animated” or expressive relates back to the minstrel shows of the 19th century, as white actors in blackface performed over-exaggerated reenactments of Black people. This minstrelsy resurfaces as ‘digital blackface’ in the current day, a term popularized by Lauren Michele Jackson, an assistant professor of English at Northwestern University and a contributing writer at The New Yorker.

Jackson writes about GIFs that feature black people being used by white people as a form of ‘digital blackface.’ Just as minstrel shows dehumanized Black Americans in the era of slavery, so too do these widely circulated images of Black reactions flatten Black people into two-dimensional characters in the modern day. Perceiving Black people as a vehicle for white emotion has dangerous real-world consequences. It decreases white people’s capacity for outrage and emotion in the cases of violence against Black people and in particular, Black women.

Social media and the advent of Black images to represent white emotion has desensitized white Americans to violence against Black women. According to Giphy, out of the 10 most popularly used GIFs of 2021, 5 of them were of people, and 3 of those 5 people were Black. The most popular GIF of 2021 was of Stanley from The Office, a Black man. The more that Black people are used as reactions by non-Black people, the faster those people move on from stories of Black people suffering. Consequently, violence against Black women does not spark white outrage to the same degree as does violence against white women.

On December 13, 2021, 23-year-old Lauren Smith-Fields was found dead in her Connecticut apartment, the day after going on a Bumble date with an older white man. Her death was initially ruled an accident by the Bridgeport Police Department, and the 37-year-old Bumble date—the last person to see her before she died—was not arrested. The lack of initial outrage from the local community following Ms. Smith-Fields’s death demonstrates how the dehumanization of Black women through online images and portrayals leads to the normalization of violence against them.

On the same day, also in Bridgeport, Connecticut, 53-year-old Brenda Lee Rawls was found dead in an acquaintance’s apartment, although her family was never officially notified of her death by the police. There was no criminal investigation opened into Lee Rawls’s death, nor was her story covered by local news until a month after her death.

Looking at these two cases of Black women’s deaths that were largely ignored by local police and media, the lack of publicity evokes not only “missing white woman syndrome” but also the dangers of white people overusing online images and reactions of Black women.

Missing white woman syndrome, a term coined by journalist Gwen Ifill, is the phenomenon of kidnapped or missing white women receiving extensive media coverage and police attention while similar cases for women of color receive a marked lack of coverage. Missing white woman syndrome prioritizes young, attractive white women, which means that women of color, especially older women of color such as Rawls, face a unique blend of racism, sexism, and ageism in having their cases underreported in the media.

This prejudice has real-world consequences for women of color: In 2015, researchers Clara Simmons and Joshua Woods found that, despite accounting for 35 percent of the National Crime Information Center’s cases, African-American missing children made up a shockingly low 7 percent of media references. By privileging missing white women while largely ignoring the thousands of Black girls and women who went missing in the United States this past year, we as a society strip Black women of humanity.

Black women can be found easily on the internet: GIFs and reaction videos of ‘sassy’ or ‘angry’ Black women dominate Twitter, and Black-created songs and sounds can be found all over TikTok. However, when violence is perpetrated against Black women, that emotion disappears. Limited media coverage, minimal police attention, and white mainstream social media channels’ evasion of discussing racial violence all contribute to the lack of white outrage over and acknowledgement of Black women’s deaths.

The idea that Black women are somehow less human, less worthy of media attention or outrage is not new. Black women have long been the victims of “misogynoir,” a unique blend of racism and sexism. Harmful stereotypes in media and film such as the hypersexual Jezebel, the sassy and impertinent Sapphire, the lazy modern day Gold Digger, or the Angry Black Woman, all contribute to people’s negative conceptions of Black women.

There is an expectation held by white people, fed by both left- and right-wing media, that Black women will fulfill one of the detrimental and reductive stereotypes so often depicted on screen. These racist stereotypes facilitate the hypersexualization of Black girls and the justification of violence against Black women. The media portrays Black women through the combined lenses of racism and sexism, engendering these misconceptions and categorizations in people’s minds so that when Black women are assaulted or killed, violence against them will not warrant the same outrage that is reserved for white women. Therefore, everyone has an individual responsibility to evaluate the media that they share and consume.

In the aftermath of Smith-Fields and Rawls’s deaths, it is incredibly important to reevaluate how the media that we share and consume in casual interactions impacts our perceptions of race. Taking individual responsibility for the GIFs that you share and the stories that you choose to read is crucial, because as long as ‘digital blackface’ continues to shape white perceptions of Black people, violence against Black women will continue to be swept under the rug.

The backlash and outrage that has ensued has largely come from Black-centered media. Black Tiktok creators raised significant awareness through videos made on the app about Ms. Smith-Fields’s case, utilizing an unconventional news source in order to tell stories that do not make it into mainstream media. Black artists such as Cardi B and rapper BIA have raised awareness through their platforms, reinforcing the media’s tendency to ignore missing Black women unless there is significant societal pressure, almost always led by Black creators and noisemakers.

Which images do you reach for when you react to a message? Whose stories are being told by the news outlet that you open every morning? For every story about an assault on a white woman, there are guaranteed to be more on queer, trans, women of color. Picking GIFs of Black people to tell a white story reinforces the racist minstrel stereotype of Black people as more animated and less real.

Allowing microaggressions to persist usually feeds another, more dangerous form of racism. Making thoughtful choices about the media that you project onto the world is just as crucial as broadening the media that you consume. So the responsibility rests upon non-Black people to think before they share and respond with equal outrage to cases with Black women as they do to cases with white women, until there is no more violence against women.