President Biden’s recent move to pardon federal marijuana offenders has drawn attention to the punitive nature of the American criminal justice system. Due to excessively harsh sentences, the criminal justice system makes it more likely that delinquents will re-offend in the future. Juveniles especially suffer from this punitive system and would benefit greatly from a more rehabilitative approach. Many young offenders who are currently imprisoned already suffer from mental health or substance abuse issues and are in need of rehabilitative treatment rather than punishment.

In the 20th century, the Supreme Court decision In re Gault recognized that children should not be treated like adults in the criminal justice system. Instead, they should be “rehabilitated” according to “clinical”—rather than punitive—approaches. However, the non-punitive approach in juvenile courts has changed dramatically in recent decades. In response to the drug epidemic of the 1980s and rise in violent juvenile crime, legislators took a harsh approach to youth incarceration. “Tough-on-crime” stances taken by public officials and propagated by the media gave rise to anxiety and fear. Prominent social scientist John DiIulio made dire predictions on youth violence and coined the term ‘superpredator.’ By describing delinquent juveniles as “radically impulsive” and “brutally remorseless,” and by using racialized language, criminologists like DiIulio induced the public to treat juvenile offenders as out-of-control criminals who deserved to be punished and separated from the rest of the population. Despite declining rates of youth crime in the 1990s, government programs provided billions of dollars in funding for youth prison construction and renovation. As a result, record numbers of juveniles were incarcerated in adult-style correctional facilities. In addition, young people were increasingly tried in adult criminal court and, in extreme cases, sentenced to life without the possibility of parole. Although juvenile crime rates have fallen since the 1990s, the harsh policies remain largely intact.

Importantly, the majority of juveniles behind bars have not actually committed a violent offense. According to an independent report, only 26 percent of youths were committed for one of the four classes of serious violent offenses in 2007: homicide, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault. Instead, many juveniles are incarcerated for repeated violations and disrespecting authorities. For example, 12 percent of youth have been placed in custody for technical violations. Oftentimes, these individuals end up behind bars at the sole discretion of the probation officer. Additionally, many of them serve long sentences in correctional institutions, despite evidence that longer stays in confinement have no impact, or a negative impact, on future offending.

It is evident that youth prisons fail to protect young people and provide them with strong prospects for the future. The facilities exacerbate many of the factors that brought juveniles in contact with the criminal justice system in the first place. Neuroscience research shows that teenagers are particularly prone to risk-taking, including criminal activity. During this stage of their lives, some teens lack the judgment to exercise self-control and fully consider the consequences of their behavior. Juveniles engaged in criminal activity, therefore, could benefit greatly from learning opportunities that address impulse control and judgment. The punitive approach of adult-model incarceration provides none of these crucial experiences.

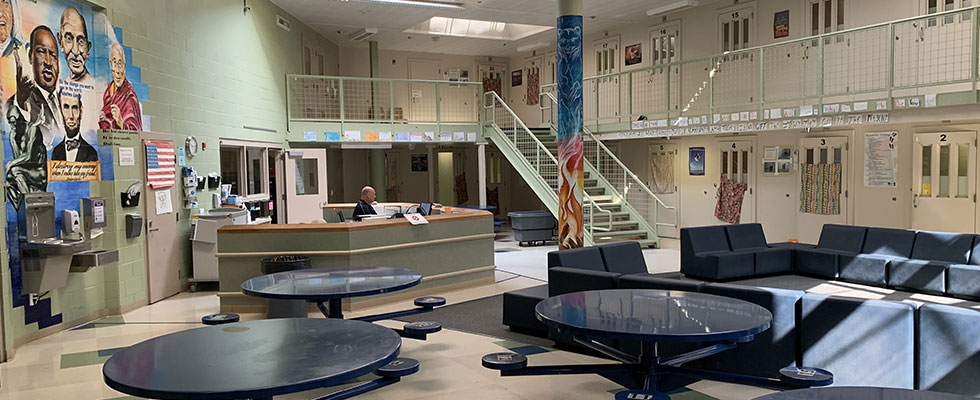

Instead, the conditions in youth prisons—often harsh, sterile environments where threats of violence and long periods of isolation are common—induce trauma and anger in their inhabitants.

These conditions inflict mental health challenges on an already at-risk population. A 2010 study found that more than 60 percent of detained youth suffered anger management problems, 50 percent exhibited signs of anxiety or depression, and over two-thirds reported substance abuse problems. Moreover, 30 percent of juveniles detained in a correctional facility stated they had attempted suicide, 70 percent had seen someone severely injured or killed, and 72 percent reported “they had something very bad or terrible happen to [them]” in the past. In addition, juveniles confined in a youth facility score four years below their grade level on average, and most have been suspended from school or had to repeat at least one grade. This suggests that incarceration exacerbates mental health, behavioral, substance abuse, and academic problems, and that the juveniles serving time in need of greater support.

However, many adolescents do not receive treatment for mental health and substance abuse issues: 42 percent of youth who reported substance abuse do not receive any treatment, and more than half of incarcerated juveniles are detained in youth prisons that do not conduct mental health assessments for all of their residents. In addition, just 45 percent of juveniles diagnosed with a learning disability receive special education services. These data suggest that the criminal justice system does not adequately address the needs of youth inmates and may not be an effective way to help them turn their lives around.

Furthermore, in many youth prisons, severe safety and abuse problems have been reported. The majority of juveniles feel they are treated unfairly in prison (55 percent), and 42 percent are afraid of being physically attacked. In addition, juvenile correctional facilities rely excessively on restraints and isolation. 45 percent of juveniles stated that “staff used force when they didn’t need to,” and 30 percent said that staff placed them in isolation as discipline. There have also been frequent reports of unchecked youth-on-youth violence and violence against staff. For example, in 2006, the Evins Regional Juvenile Center in Texas documented an average of three assaults every day. These inhumane conditions demonstrate that youth prisons in the United States usually do not meet their stated purpose of rehabilitation. Even when these facilities do provide educational and treatment opportunities, it is difficult to imagine that juveniles will be able to make the most of them while living in an environment permeated by fear and violence. The power dynamic between the young prisoners and guards further exacerbates juveniles’ feelings of submission and control within the facilities. This guard-versus-prisoner relationship is found in adult prisons, but it is heightened by the power differential that already exists between children and adults. As a result, juveniles lack exposure to positive relationships with adults, guidance, and role-modeling.

As the high recidivism rate for adolescents indicates, youth prisons do not effectively discourage young people from committing crimes. Seventy to 80 percent of youth are rearrested within two to three years of being released, and 45 to 72 percent of youth released from juvenile correctional facilities are found guilty of a new offense within three years. Though imprisonment is supposed to serve as a deterrent to breaking the law again, it may increase the chance of recidivism by diminishing a young person’s chance of good future prospects. Many juveniles in confinement grow up in high-poverty neighborhoods, suffer from learning and mental disabilities, and underperform academically already, so incarceration adds yet another barrier to success. Furthermore, youths can accumulate “criminal capital” in prisons. This means that prisons may serve as “schools of crime” that teach juveniles how to evade police capture and increase earnings from crime, which, in turn, leads to further offenses and criminal activity after confinement. Contact with other criminals in juvenile prisons may even require confined youths to behave in an aggressive manner to avoid attacks by others—behavior that may continue after incarceration.

The juvenile justice system must be radically reformed. Beyond limiting the eligibility for incarceration and decreasing the length of incarceration, non-violent and low-level offenders should not end up behind bars, and no juvenile should spend their entire life in prison. Research has shown that longer stays in prison do not reduce the chance of reoffending—though they take a considerable toll on state budgets and juveniles’ prospects for the future. Closing some youth prisons would enable increased investment in facilities and living conditions for the detention centers that remained, as well as improved social welfare and educational programs.

Furthermore, alternatives to confinement should be expanded, particularly community-based and family-centered programs. This would give judges more flexibility in matching youth offenders with effective programs. Multisystemic Therapy (MST) and Functional Family Therapy (FFT) show promise, for example. MST involves a three- to five-month long intervention process led by therapists who visit the family’s home several times a week. FFT conducts an average of twelve counseling sessions designed to support meaningful behavioral changes that address the underlying causes of delinquent behavior. These programs have shown 25 to 70 percent lower rearrest rates compared to incarceration without access to similar services.

Juvenile correctional facilities themselves should also be reformed. In Missouri, over thirty years ago, youth prisons were replaced with small, community-based juvenile correctional facilities that created a more hospitable environment and offered treatment-oriented programs. These facilities are located closer to the young people’s families and communities and provide rigorous vocational training programs, cognitive-behavioral skills training, intensive mentoring programs, and specialized mental health and substance treatment models. As a result of this individualized and extensive approach, young people are encouraged to make behavioral changes that will help them manage better in regard to jobs and relationships. Moreover, corrections staff receive high quality training on adolescent development, so they can deliver trauma-informed care to the youth they supervise. These close relationships between caring, motivated, and extensively trained adults and young people foster trust, compliance and safety. This rehabilitative approach seems to be very successful: Missouri reports that only 6.6 percent of youth return to the juvenile or adult prison systems within three years of release.

At the moment, the American juvenile justice system is much too punitive, as juveniles are incarcerated for minor offenses and must endure long stays in adult-like correctional facilities (or even actual adult prisons) that foster an environment of fear and violence. Small, community-based juvenile correctional facilities and various rehabilitative programs have proven to be much more effective in reducing recidivism—not to mention the much more humane conditions. As the juvenile crime rate continues to drop, states can invest more in alternatives such as rehabilitative programming, education, job training, child welfare, and mental health systems. This will allow states to finally address and mitigate the sources of juvenile delinquency.