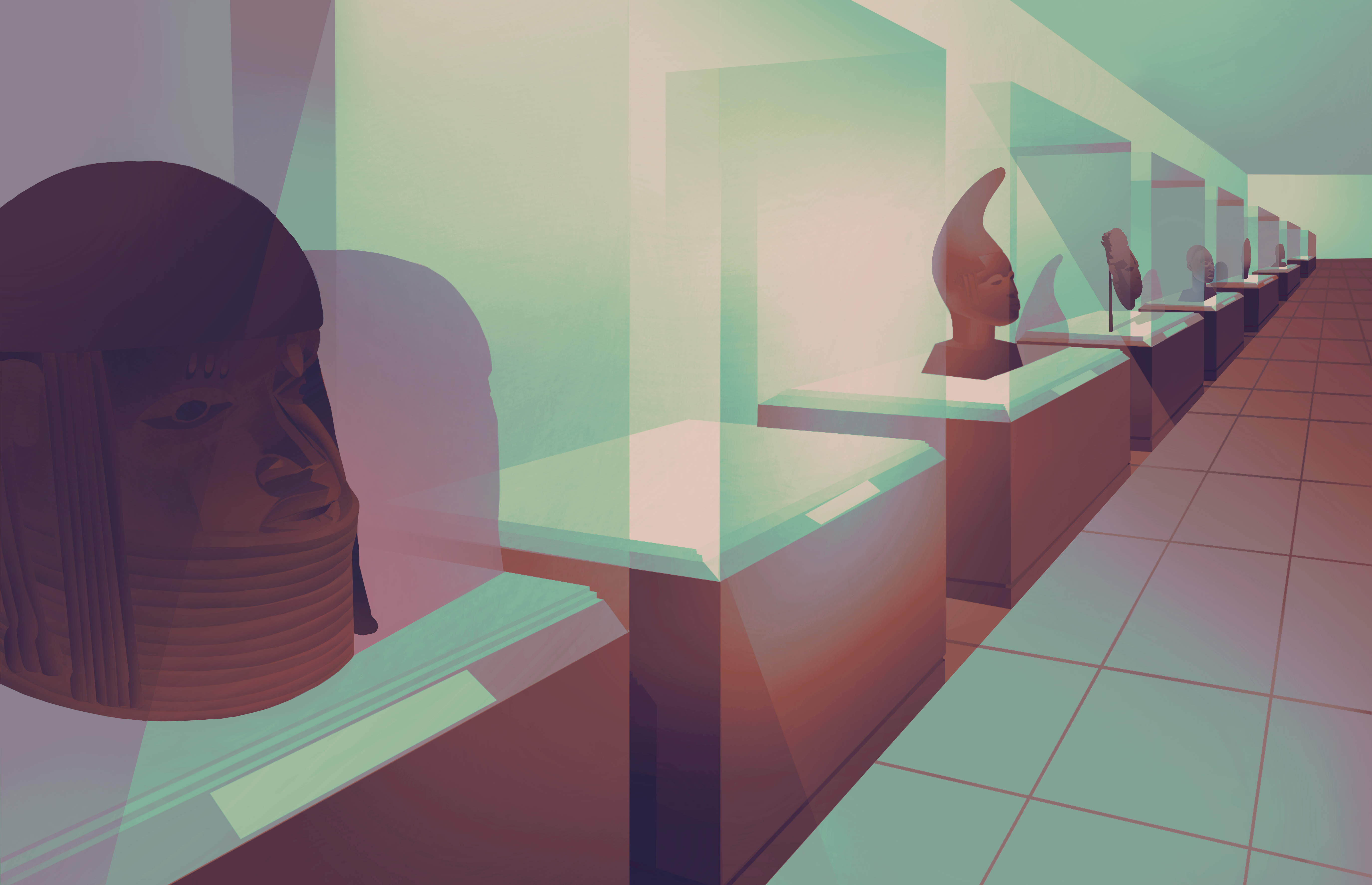

On October 11, 2022, The Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum returned its long-contested Benin Bronze Heads to Nigeria. The RISD Museum is one of many museums around the world that have begun to repatriate bronzes from the Benin Kingdom that British colonizers looted during the Benin Punitive Expedition. The museum had also been in discussion with the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments—a government organization dedicated to the restitution of goods and artifacts to museums in Nigeria—since 2018, and, after four years, the bronzes finally made their way home with little fanfare.

This is not the first case—and certainly not the last—of private universities housing unethically sourced collections or grave goods. In 2021, the Harvard Peabody Museum was reported to have at least 19 enslaved remains in its collection and “thousands” of Indigenous remains, according to an unfinalized report released by the school newspaper, The Crimson. The Peabody Museum Director, John Pickering, formally apologized for its role in the nonconsensual collection of human remains, stating the museum’s intended to “prioritize the urgent work of understanding and illuminating our history and to begin to make amends.” In spite of The Peabody Museum’s recognition that it had been slow to act in accordance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), it did not lay out an action plan to repatriate the thousands of Indigenous individuals in their archives. The framework of NAGPRA, though not faultless, provides a critical basis for a new piece of legislation: an act to protect the grave goods and cultural heritage of African descendants.

NAGPRA, passed in 1990, dictates that all federally funded institutions on federal or tribal lands must return “possession or control of Native American cultural items to lineal descendants” that are “culturally affiliated” with a federally recognized tribe or Native Hawaiian organization. As such, any museum or collection that receives federal funding after November 16, 1990, was expected to comply fully and expeditiously. With so much time and such clear direction, why are universities and museums lagging behind on restitution?

This question is indicative of a larger attitude towards repatriation in the United States. In 1970, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) hosted a convention aimed at ending the illegal antiquities trade of cultural property as a response to former colonies gaining independence. The convention resulted in three core principles, one of which stated that nations are responsible at the national level to take “appropriate measures to seize and return” cultural property. It wasn’t until September of 1983 that the United States accepted the Convention, and it has yet to ratify it.

Even upon accepting the Convention, the United States emphasized its ability to “determine the extent of regulation” in accordance with the US Constitution instead of any international law or agreement. The apparent apathy of the US government towards meaningful repatriation of cultural property is passed down to the public and private institutions that populate the world of academia and museology, resulting in collectors who twiddle their thumbs as communities demand their material heritage back. This negligence is exemplified in the case of African-descendant remains: In April of 2021, the remains of two Black girls (Tree and Delisha Africa) were found at the University of Pennsylvania and Princeton University having been used for scientific research without the consent or knowledge of their families. These two girls were victims of the 1985 MOVE bombing, in which the Phildelphia Police Department decimated an entire city block and killed 11 people. Even in death, Black Americans continue to be disrespected by powerful and wealthy institutions; even in death, Black bodies continue to be brutalized under the approval of white supremacy.

There have been efforts by legislators to federally protect African American cemeteries through the National Park Service. In February of 2019, Representative Alma Adams (D-NC) introduced the African American Burial Grounds Network Act, only for it to fade out of relevance upon reaching the House of Representatives that May. As recently as February 2022, Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) introduced the bipartisan African American Burial Grounds Preservation Act, which hopes to combine tribal and federal efforts to research, document, and preserve African American cemeteries. However, the bill was placed on hold after being introduced to the House, and no news has been heard thus far. Still, these pieces of legislation do not grapple with the legacy of slavery in university and museum collections, nor does it provide substantive requirements for repatriation. Without legislation similar to NAGPRA (though with a stronger enforcement mechanism), the bodies and funerary goods of enslaved Africans and their descendants remain at the mercy of the institutions that unethically house them.

So what legislative actions should Congress take to protect and return African-descendant remains and material culture, and what provisions should make up this act? Using NAGPRA as a base, I propose an African-Descendant Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (ADGPRA): I purposefully use the terminology “African-descendant” to emphasize that the repatriation of goods should not be limited to descendants of enslaved Africans, but rather be expanded to include all goods stolen from African or African American communities, at home and abroad. ADGPRA has three main principles: prioritizing noninvasive identification of remains for the purposes of reporting and repatriation; ceasing urban development projects upon the discovery of African American gravesites, followed by the preservation of these gravesites; and active participation of descendant communities in deciding what happens to remains after they are recovered.

NAGPRA similarly emphasizes the identification of human remains and associated or unassociated funerary goods for the purpose of both inventory and restitution. However, NAGPRA’s requirement for the remains or artifacts to be “reasonably culturally affiliated” to a federally recognized tribe does not allow unrecognized tribes to make claim to their ancestors or cultural property. Without operating through tribal nations, African-descendant communities circumvent this problem while simultaneously arriving at another one. What do we do with the remains of individuals that we cannot identify? Writers at Nature recommend that biological data and DNA analysis should be used with informed consent from descendant communities in order to approximate the heritage of the deceased individual. However, ADGPRA would advocate for genealogical histories to be constructed from archival and community-based research that aims to preserve the remains as they were originally found, when possible. If remains continue to be unidentifiable, instead of remaining in the institution’s collection they should be buried at a national cemetery for once-known ancestors, similar to the African Burial Ground Monument in New York.

Furthermore, newly discovered burial grounds of African-descendant communities, free or enslaved, must be protected. Many cemeteries of the formerly enslaved are discovered in the process of urban development, such as the one that NPS turned into the African Burial Ground National Monument, where 20,000 African remains were buried from 1630s to 1795. Construction on top of these sites disturb the archaeological context of these burials—which can tell us much about Black culture and society in the times of enslavement—as well as disrupt those at peace. As such, documentation and preservation of these sites are crucial, and require a team of expert archaeologists, historians, as well as Black community members from the area in order to navigate the tumultuous waters of what to do with burial sites when they happen upon them. Similar to the African American Burial Grounds Preservation Act, ADGPRA would protect these sites whilst also attempting to identify the ancestors present in order to allow their descendants to properly bury and mourn them. While experts should be presented with the opportunity to further reconstruct the life of Black people in the Americas through research, the priority of ADGPRA would always be the respectful return of these individuals to their community or places of rest.

The treatment of African American remains and artifacts of the Black diaspora in the United States is a symptom of its settler colonial heritage, in which the economic and aesthetic value of an object to historically white institutions outweighs the cultural value to the communities from which it was stolen. While NAGPRA is a revolutionary piece of legislation that attempts to combat the possessive culture surrounding bodies and their funerary goods, its faults are still indicative of a need for a more concentrated effort to hold museums and university collections accountable. My proposed African-Descendant Graves Protection and Reparations Act would build upon the invaluable work of Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous activists to further push the United States to recognize and rectify the harm of unethical collection practices. By working from the top-down, Congress would set the tone as to how federally funded institutions should engage in restitution with marginalized communities, as well as prioritize the meaningful repatriation of stolen goods. It is when our heritage and ancestors are returned to us that we may begin the process of healing from the wounds of settler colonialism and slavery.