“I’m not going to be able to do anything more… this is my only option,” a single working-mother of three told a phone counselor at the Women’s Medical Fund in November of 2017. With only $125 in savings, she was forced to turn to a private abortion fund to help pay for expenses that her insurance would not cover and her family could not afford. Tragically, stories like this one are not uncommon. Worse, some women are altogether unable to access reproductive healthcare during their pregnancies, leading to forced birth.

Forced birth is gendered violence. First and foremost, it is a clear violation of bodily autonomy. Beyond that, it also traps people in cycles of structural violence from which they have little hope of escape. The Guttmacher Institute reports that “women who do not obtain an abortion they wanted have four times greater odds of subsequently living in poverty and three times greater odds of being unemployed six months later, compared with women who are able to obtain an abortion.” Moreover, women forced to carry unwanted pregnancies experience higher rates of medical complications, chronic pain, and worse overall health outcomes than those who receive their desired care.

In theory, prior to the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization Supreme Court decision, the federal government protected the fundamental right to choose for people across the nation. But for many, this was a right in name only. The stories of people who struggle to pay for reproductive care are too often left untold—they are confined to the solemn halls of doctors’ offices, desperate phone calls with help lines, and hushed conversations with loved ones. Nevertheless, these stories are all around us.

This silent suffering is not inevitable. The federal government once funded over 300,000 abortions annually through Medicaid, a program which provides health insurance to roughly 80 million low-income Americans. But in 1980, that number dropped to almost zero. The cause of this precipitous decline? The implementation of the Hyde Amendment.

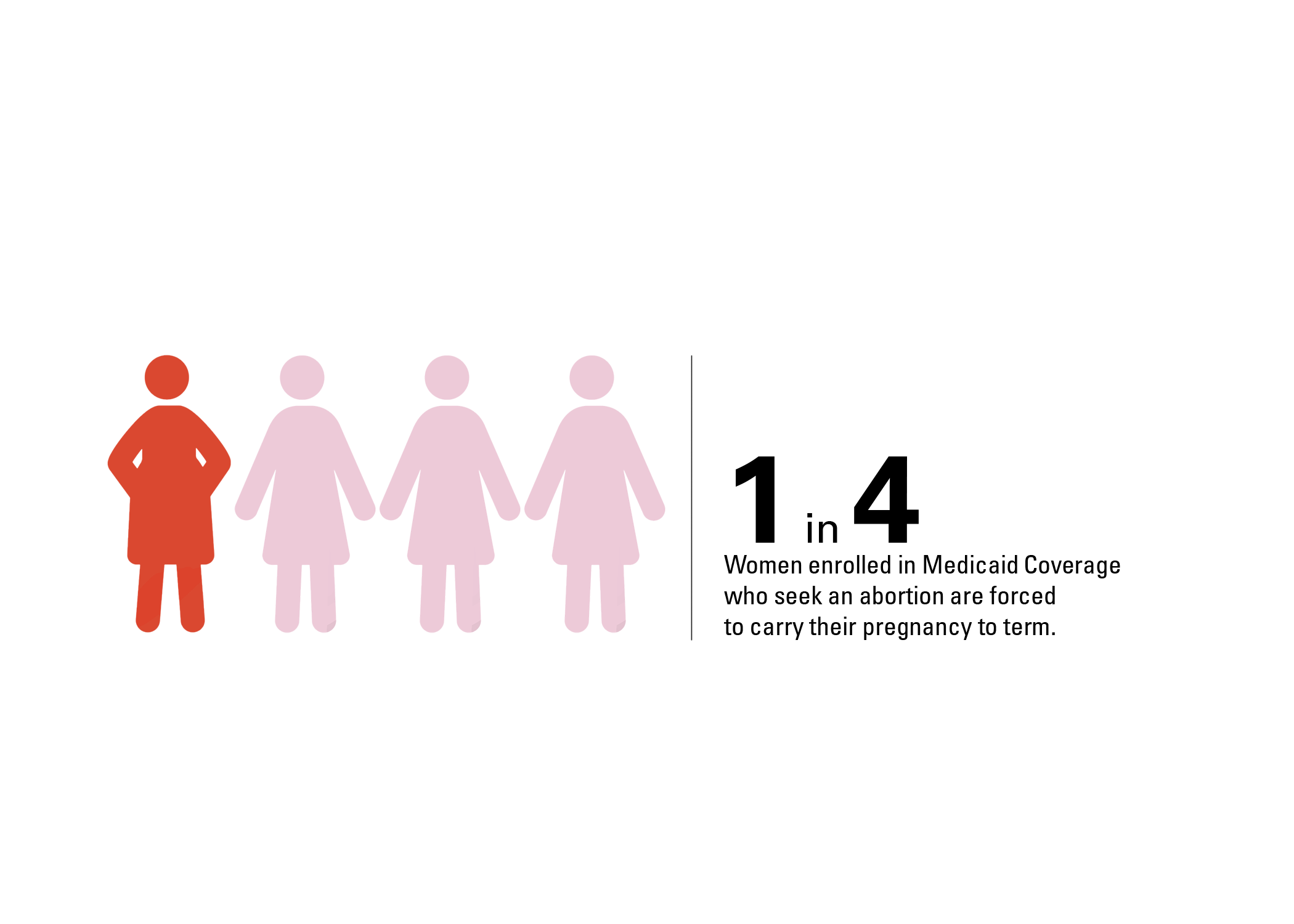

Included in annual appropriation bills since the 1970s due to pressure from pro-life members of Congress, the Hyde Amendment prohibits the use of federal funds to cover abortions. This means people on Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) must pay for abortions out of pocket. This restriction places an undue burden on those who are precisely the least able to afford it: Half of the women and girls of reproductive age who live in poverty are enrolled in Medicaid. For these individuals, paying hundreds or even thousands of dollars is a huge, often insurmountable barrier to receiving care. Consequently, in states that do not fund reproductive healthcare themselves, one in four women on Medicaid who seek abortions are ultimately unable to obtain them.

A congressional repeal of the Hyde Amendment would be the most effective way to minimize forced birth across the nation and help ensure that all people—regardless of income, veteran status, or incarceration—have the right to choose. However, such a repeal currently faces an uphill battle in the Senate due to united Republican opposition, as well as pushback from a few Democrats. Thus, one critical near-term goal for reproductive rights activists should be pressuring states to cover the costs of abortions for people on federal insurance.

While some states already cover abortion costs, the majority do not—nearly eight million women across 34 states and the District of Columbia are directly affected by the Hyde Amendment. And in Colorado, Delaware, Nevada, and Rhode Island, Democrats have failed to act in spite of the fact that they hold trifectas in state offices.

Far too often, even women who are able to get abortions must do so at great personal cost. In one study, more than half of participants spent over one-third of their monthly income on the procedure, with many delaying paying their bills or foregoing meeting their material needs. And even with these sacrifices, over half of the women in the study were forced to defer their abortions to raise money. These delays not only raise the costs of the procedure itself, but also increase the likelihood of medical complications.

While some defer or forego care, others, like Rosie Jimenez, resort to unsafe methods. When the Hyde Amendment took effect, Jimenez was a 27-year-old college sophomore on Medicaid. Because her insurance would not cover the costs of her abortion, Jimenez could not afford to see an Ob/Gyn to obtain the procedure. So, lacking other options, she turned to an unlicensed midwife. After days of bleeding, Jimenez died of an infection, leaving behind her four-year-old daughter.

Jimenez’s widely publicized story has led her to be called the “first victim” of the Hyde Amendment—but she was certainly not the last. And because of the intersections of race, gender, and poverty, repealing the Hyde Amendment is an issue of social as well as economic justice. Nearly 30 percent of all Black women between 15 and 49 were enrolled in Medicaid in 2019, and Black women seek abortions at higher rates than their non-Black counterparts. Furthermore, Black women experience disproportionately high rates of maternal mortality when they carry pregnancies to term. Together, these facts illustrate a harrowing reality: Black women are disproportionately likely to seek access to abortion care; disproportionately likely to be denied such access; and disproportionately likely to suffer the consequences of those denials.

The Hyde Amendment also hurts other groups who rely on federal funding for their insurance, including many government employees, veterans, federal prisoners/detainees, and Native Americans. For people who are incarcerated, this can mean carrying unwanted pregnancies to term within prison walls and without adequate medical care; giving birth in shackles or solitary confinement; and being separated from their newborn children. For Indigenous women, the Hyde Amendment represents just one of many violations of their bodily autonomy. Many Native health clinics delay care due to understaffing, fail to provide emergency contraceptives, and, until recently, did not reliably offer birth control.

This is particularly concerning given that Native women are the most likely to experience rape of any ethnic group. While the Hyde Amendment does now carve out exceptions for rape (as well as incest) on paper, actually obtaining funding in these circumstances is a different story. The amendment’s narrowly tailored limitations create bureaucratic hoops for patients and providers to jump through; an analysis published in the American Journal of Public Health conservatively estimates that, of 1,165 abortions that “qualified for federal Medicaid funding in the year before the interview, 736 were not reimbursed.”

Like Native women, people in the armed forces are also disproportionately harmed by these bureaucratic obstacles. In fact, almost a quarter of servicewomen are survivors of sexual assault. That women who sacrifice their bodies for their country are denied the right to bodily autonomy by the very nation they serve is a disgrace.

By funding abortions for those who want them, states could take a step towards resolving these injustices. Moreover, in addition to helping pregnant people in their own states, funding insurance for abortions would also enable blue states to indirectly protect the rights of women in red states by reducing the pressure on abortion funds. This is particularly relevant in the wake of Dobbs, as thousands of people must now take time off work, organize childcare, and cross state lines in order to receive basic medical treatment. These additional expenses, which can reach over $4,000 per person, have further strained already under-resourced abortion funds. In ensuring that their own residents can use government insurance to pay for abortions, liberal states can enable abortion funds to assist more women in anti-abortion states.

The time to act is now. Pro-life advocacy groups have achieved enormous legislative success despite their relatively small base through the persistent and passionate advocacy of their most zealous supporters. Now, pro-choice groups may be ready to bring the same level of energy. After Dobbs, people across the nation are particularly alert to issues of reproductive justice; a recent Pew poll found that 56 percent of midterm voters currently consider abortion a top voting issue, in comparison to less than 40 percent a decade ago. Moreover, 71 percent of registered Democrats now say abortion rights are very important to their vote, indicating that we are in a potentially time-sensitive moment for the expansion of reproductive rights. With the political wind from Dobbs at their backs, liberal states have a critical opportunity to connect the right to choose in theory with the right to access in practice.