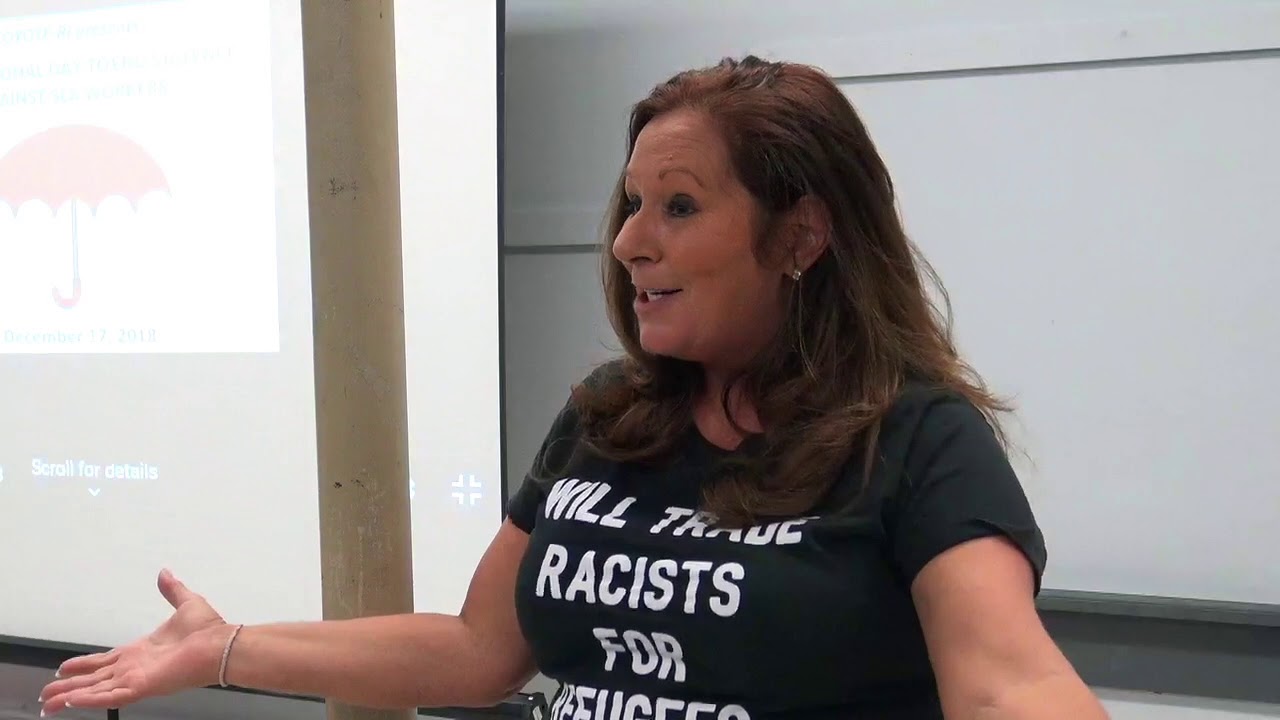

Bella Robinson is the Executive Director of COYOTE-RI (“Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics”), the first sex workers’ rights organization in the United States. A sex worker of 35 years, Bella is deeply involved in legislative and legal advocacy, community organizing, research, and data collection in pursuit of decriminalizing prostitution. Bella has served as a FreeHer Fellowship Facilitator, a board member of The Erotic Service Providers Union Legal, Education and Research Project (ESPLERP), and on the advisory committee of the Sex Worker Outreach Project (SWOP) Behind Bars. She has shared her story with Vice and in the documentary American Courtesans, drawing on her experiences of familial and marital abuse, escaping the foster care system, homelessness, entering the sex work industry at age 18, her time within the criminal justice system, and life as a mother and “hooker.”

Alexandra Lehman: Much of your advocacy centers on changing common perceptions surrounding sex work. What do you believe to be the most pervasive and damaging misconceptions about the industry and those who participate in it?

Bella Robinson: There is too often a narrative of victimization that erases the many experiences of sex workers. It is inaccurate to say that consensual sex work between adults is the same as sex trafficking. A lot of us don’t like to be called victims; the fact that they frame this as “modern-day slavery” is a real insult to our history. If anything, I feel like I’m a victim of state-sponsored violence. Laws that criminalize prostitution hurt both sex workers and decrease the effectiveness of efforts to actually help those that are in the industry without choice. So much data is skewed to suggest that all sex workers are exploited, vulnerable, and desperate. There is no recognition that some of us choose to enter the field, and even within the system, we can exert choice. So, as far as the sex industry goes—there are all different types of empowerment.

Within the “nonprofit industrial complex,” narratives of trafficking become convenient. Then, law enforcement uses this to crack down on and arrest sex workers, rather than help the smaller proportion of people actually being trafficked. When they turn you into only a victim, you can’t speak up. You can’t claim full rights. We have surveyed thousands of sex workers about their experiences. What we found is that the majority of violence is fueled by the criminalization of prostitution.

When violent things happen to sex workers, we have a narrative that “bad women” get what they deserve. Under decriminalization, when you have no legal rights, the police are not on your side. You can’t vet clients as well and you can’t use law enforcement to protect you. This is why so many sex workers end up dead or missing. We don’t care about catching these predators. Instead, we blame the victims. Our legal frameworks are completely insufficient. Instead, we give all the power to the predator.

The most frequent question asked to sex workers is, “Well, why do you get into it?” “Well, why did you go to work for Walmart?” “Why are you going to school?” We all work because of capitalism, we all need money. If any one of us was cold or hungry enough, we could be convinced to turn a trick. We are dehumanized and treated with disdain—like we’re something other than everyone else. I hate when politicians talk about “family values.” Your family values might just look different than mine. And your “values” certainly don’t include the protection of my well-being.

AL: Until 2009, Rhode Island inadvertently decriminalized sex work via an “indoor prostitution loophole.” What did the experience of working and living under two different legal frameworks entail?

BR: When I came to Rhode Island under decriminalization, I felt free for the first time in my life. Game changer: I can tell on you and I can’t be arrested. We had sex workers in Rhode Island who avoided murderers like the “Craigslist Killer” because they could dial 911. When they took it back, I was really angry. I started learning about the sex worker rights movement that had been going on for over 30 years. When so many sex workers were suffering, being imprisoned, or being murdered with no one caring, I found my calling.

AL: How do you envision the future of the fight for decriminalization?

BR: Now, I think the most important challenge will be shifting social perception. When we look at the political parties, they will stand up for different communities. But the one group it’s okay to hate on regardless of your politics is sex workers. The media always portrays us as half-naked; Hollywood has stigmatized us from the beginning of time. Everyone profits off the trafficking narrative and nothing trickles down to the people involved in the sex industry. I used to think that decriminalization was the answer, and once we won it, everything would be wonderful. We can look to other social movements, like the fight for LGBTQ+ rights, where even once certain legal battles were won, it took decades to shift social perception. Even if we win decriminalization in any of these states, they’re immediately going to try to take it back like abortion. This will be a multigenerational fight.

AL: What is the current state of sex work advocacy in Rhode Island? What are your hopes for COYOTE?

BR: It took us three years to get H5250 [Rhode Island House Resolution on “Creating a Special Legislative Commission to Study Ensuring Racial Equity And Optimizing Health and Safety Laws”]. It was supposed to be a commission for sex workers, but then it got a lot broader. I am the only sex worker on the commission.

We drafted a bill, S2713 [An Act Relating to Criminal Offenses—Commercial Sexual Activity], that would decriminalize sex work and expand eligibility for the expungement of related criminal records. It was introduced by Senator Mendes, and we had help from the ACLU. We are also supporting S2716, S2233, and H7704, which are imperfect but are a step in the right direction. We have been gathering testimony and will be having a hearing. Unless I’m dead, I’ll be there.

Our main goal is to start to shift social perception and show how much harm criminalization is doing to women. We know that the bills won’t get out of committee. However, our strategy is to keep pushing, to keep the conversation going, and to educate legislators. Unlike me, they don’t have 35 years of experience as a sex worker, they didn’t go to prison, they didn’t overcome a crack addiction—they have no life experience, nor have they surveyed sex workers. This is why we need to include our voices. We are mothers, we are daughters, and we are your community members. We’ll keep fighting and we’ll hope for the best.

Let’s do this again soon. I’ve got to run off to the State House.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.