In January 2023, New York State Governor Kathy Hochul announced that the Interborough Express—a future New York City transit line that will connect Brooklyn and Queens—would officially move ahead. The benefits of the Interborough Express are profound: It is predicted to have 115,000 daily riders, significantly reduce commute times between Brooklyn and Queens, connect to 17 existing subway lines, and “expand economic opportunities for the people who live and work in the surrounding neighborhoods.” The line is also a notable step away from the ‘Manhattan-centric’ subway system that currently exists in the city, allowing for direct transit options between the outer boroughs and historically “underserved locations.”

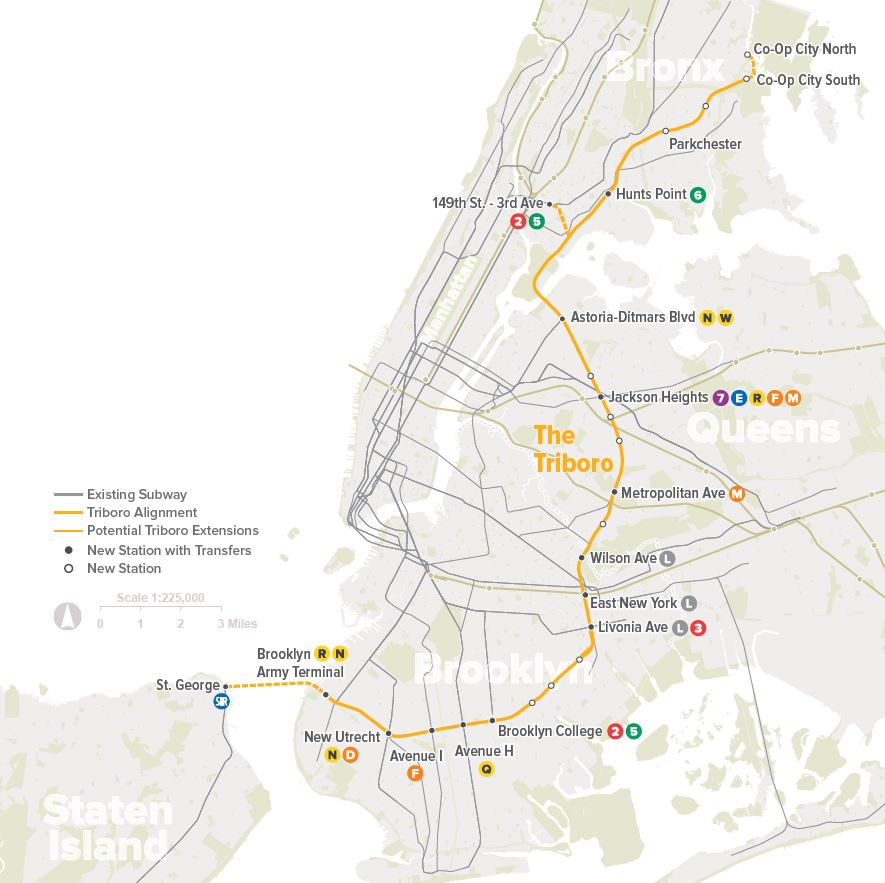

However, despite the range of improvements that could come with the establishment of the Interborough Express, official plans for the line notably exclude the Bronx. Despite past iterations of the Interborough Express all including multiple stops in the Bronx, official statements from Governor Hochul have omitted the borough’s potential inclusion with no explanation as to why. Not only does the Bronx’s exclusion from the Interborough Express reinforce a history of transit inequity, but including the Bronx in more substantial public transportation plans like this one can help rectify past transit wrongs.

The Bronx’s overall history is inextricable from the history of public transportation in NYC at large. The development of the Bronx’s first subway lines, completed in 1904 and extending up from Manhattan, helped to urbanize what was then mostly farmland with a population of only 200,000 people. Providing new means for people to live in the (more affordable) Bronx while commuting to Manhattan for work, the Bronx population increased to just over 730,000 in the two decades preceding the subway’s opening, and almost doubled to 1.4 million twenty years later in 1950. Around the time the Bronx reached one of the highest population densities in its history, the NYC subway at large reached over 2 billion annual NYC subway rides in 1946, the most in its history.

While public transportation has had a positive impact in the Bronx—sparking mass urbanization and allowing for easier movement between the Bronx and Manhattan—the Bronx’s history has also been riddled with blatant instances of transit inequity. In an infamous example, city planner Robert Moses designed the Cross Bronx Expressway to run through seven miles of already existing Bronx neighborhoods in the 1940s. However, as a result of this construction project, over 60,000 residents were displaced, property values dropped, and the Bronx’s public transportation and other public services were left severely underfunded and underdeveloped. By the 1960s, the Bronx was a predominantly Black and Hispanic borough, and has remained so to this day. As such, the neglect to the borough’s infrastructure disproportionately affects large populations of racial minorities, making it a blatant example of systemic racism in NYC.

The impacts of the mass disinvestment in the Bronx’s infrastructure are still being felt today. While 60 percent of Bronx residents do not own cars, indicating widespread reliance on the city’s public transportation system, there is a lack of efficient transit options to travel within the Bronx, or from the Bronx to the outer boroughs. Within the Bronx, a 20 minute drive between neighboring areas turns into an hour-long commute with multiple transfers taking public transportation, and––to commute from the Bronx to Queens––only two bus lines are available.

This gap in transportation is particularly notable when considering the 41.6 percent of employed Bronx residents who work either within the Bronx or a borough other than Manhattan. In general, areas with insufficient transportation access in New York City also face high rates of unemployment. However, elongated transit times from the Bronx to the outer boroughs can further economic divides: Not only do many employees have to deal with the hassle of a long commute, but major delays can massively impact their ability to get to work on time, possibly jeopardizing their jobs. In a borough where 24.4 percent of residents live in poverty, making it the poorest county in New York State, the added economic effects that transit inequity has on the borough are even more poignant.

Community activists and politicians have also pointed out the inequities that exist in the Bronx’s public transit system, especially in the light of the recent exclusion from the Interborough Express line. State Senator Jamaal Bailey told The Bronx Times that expanding the Interborough Express into the Bronx could be “transformative” for Bronx residents who live in “some of the most transit-starved neighborhoods in the city.” Similarly, Maria Torres, the president of The Point, a Bronx-based community development corporation, told Gothamist that the Bronx’s exclusion from the new line signified a loss of potential job opportunities in the borough.

In an ideal world, a large step towards reducing some of the systemic transit inequities in the Bronx would be for the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) and Governor Hochul to create concrete plans to include the borough in the future of the Interborough Express. However, given the MTA’s chronic issues with exorbitant project costs and inefficient construction, plans for the Bronx’s inclusion seem highly unfeasible (at least for the immediate future). Despite this, there are some more immediate actions that the MTA and New York State government can take to concretely improve upon the Bronx’s transit situation, some of which focus on the borough’s bus system.

While the addition of more subway infrastructure would greatly benefit the Bronx, more people rely on the bus system in the Bronx than any other borough per capita (likely to replace the lack of subway service). Strengthening the Bronx’s bus system––through redesigning or adding new routes––would work to serve riders who are in need of transportation within the borough or to Brooklyn or Queens. The benefits of this have already been proven on a small scale: After the MTA revamped the Bronx’s bus system in 2022, bus route speeds increased by 4 percent and ridership rates increased by 6 percent. Expanding this initiative to the bus routes that run between the Bronx and Queens, specifically adding more routes between the two boroughs, could have similar effects; ridership, job opportunities, and bus line speeds can be increased, all while being less costly than constructing an entirely new train line.

While there are substantial amounts of work left to completely solve the Bronx’s issues with transportation inequity, developing concrete plans where the Bronx’s bus infrastructure is prioritized is one immediate and feasible solution. However, the MTA and state government should still work to consider long-term, substantial updates to the city’s subway lines to continue serving residents of the Bronx. As the MTA’s operation and infrastructure currently stands, it perpetuates histories not only of transit inequity, but class and race-based disparities. However, by working with residents, activists, and local politicians, the MTA can redesign and enhance bus routes to serve the authentic needs of community members, combating a history of Manhattan-centric transportation options.