This is the second installment of Housing as a Human Right, a BPR interview series on the housing crisis in Rhode Island.

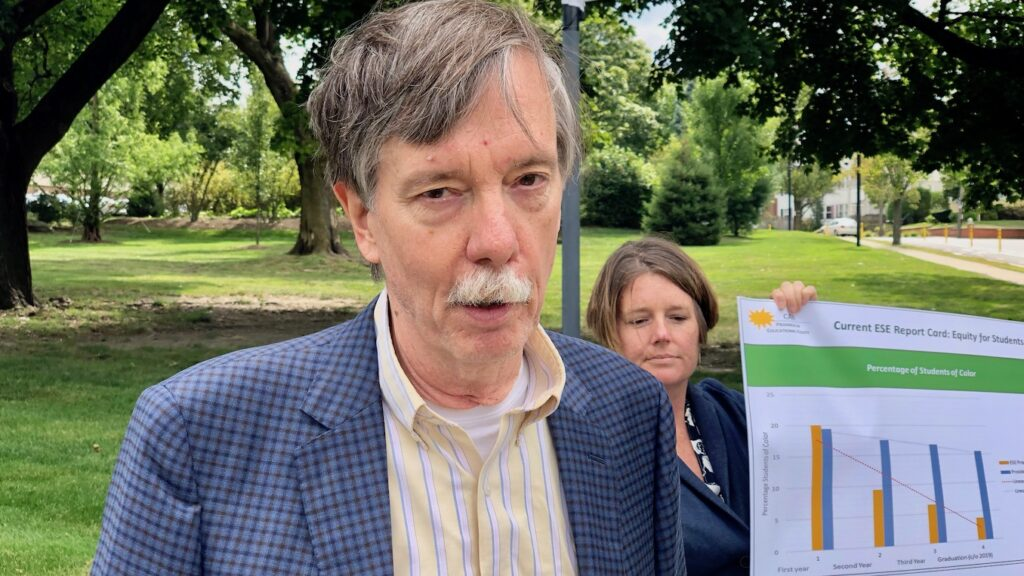

Eric Hirsch is a distinguished urban sociology professor at Providence College. He spends much of his time outside of the classroom, working with community groups such as the Rhode Island Housing Advocacy Project to advocate for housing justice in Rhode Island.

Ben Ringel: I understand you lead the Rhode Island Homeless Advocacy Project, and you’re also a professor of urban sociology at Providence College. What led you to be passionate about urban space and the housing crisis?

Eric Hirsch: I went to graduate school at the University of Chicago, and I got involved in a research study looking at the area surrounding the University of Chicago, which is essentially a segregated black community: South Side Chicago. That’s when I really got interested in housing and urban sociology as well. In a situation where there were so many homeless people and simultaneously so much unoccupied housing, there had to be an issue. Then, I got a job at Columbia University, and I was there for eight years. I focused a lot on urban issues there as well.

BR: What brought you to Providence?

EH: Columbia was not a place where I was going to get tenure. That was in part because of a variety of political movements that I was part of at Columbia, one of which was an anti-apartheid movement. I was part of the faculty in support of students who took over the main administrative and classroom building of Columbia College for three weeks, trying to get the college to sell their stock in companies that were doing business in South Africa. I helped unionize the administrative support staff as well, and was part of probably four or five other movements that the administration did not particularly like. I didn’t expect to get tenure there, but I got an offer from Providence College, and so I ended up here.

BR: What led you to begin advocacy work?

EH: I was very involved in tenant organizing for the Hyde Park Tenants Union in Chicago and the Morningside Tenants Federation in New York City. Both of those were movements that tried to deal with the attempts by the University of Chicago and Columbia to dominate the rental market and to get as much territory as they could possibly acquire. I was seeing that as part of gentrification, in both places, upper-level administrators and faculty members were taking over buildings and displacing people of color, often lower-income people of color. When I got to Rhode Island, I looked for a tenant organization and there really weren’t any, but I got much more interested in the topic of homelessness in Rhode Island and have been working on that issue ever since.

BR: What are local groups in Providence and in Rhode Island pushing for right now, in relation to homelessness?

EH: When Covid-19 hit, we were really focused on density precautions in shelters, and also fighting for the government to open up hotel rooms and other spaces for the people that the pandemic pushes to the street. During the coronavirus pandemic, we did have support from FEMA, rent relief, and a moratorium on eviction, but all of that went away and there are still so many people outside. We’re working on getting some of these protections and open spaces back.

BR: Do you think it’s local organizations pushing the needle and setting the agenda, or has this work been primarily fueled by the will of politicians?

EH: So often when politicians say we’re going to end homelessness, you find out by the end of the development process that it’s for upper-income, middle-class people, partly because you don’t need as deep of a subsidy when you’re developing housing for middle-class people. I think our role is to make sure that they focus on people who are living outside or in shelters. They have the greatest need. Our role is to protest because homeless people don’t have money to contribute to campaigns or go hire lobbyists. The only tool we have is to protest and to emphasize the importance of this issue.

I would say the most powerful person in the state is the Speaker of the House, [Rep. Joe] Shekarchi. He’s stepped up to the plate and really talked about prioritizing housing for very low-income households. We will hold his feet to the fire and do what we have to do to make sure he comes through with that.

BR: As a Brown student, I’m a part of HOPE, a club that sends students to do direct outreach with the unhoused population of Providence. It’s always striking to be in a place like Kennedy Plaza, full of people in dire need of help, and then walk just five minutes, up the hill, back to the campus bubble, where so many people have never meaningfully engaged with the realities of the things they study. What’s the best way to incorporate engaged scholarship into academia? How do we connect the realities of the people we study to the work we do?

EH: The truth of the matter is that if you’re a professor teaching about anything related to social issues, you can’t be abstract about it. If the students aren’t understanding the lives of the people experiencing this issue, especially in the city of your school, that’s a failure in my mind. The ivory tower is not acceptable, and as someone who has worked with groups like HOPE before, direct outreach is exactly how we should be framing our teaching.

BR: How do your academic studies and understanding of urban sociology impact your organizing? Conversely, I think a lot of times academia can be very disconnected from the reality of the issues they study, so how does your work with people on the streets inform both your teaching and your research?

EH: I’ve always been an activist first. I’m against purely theoretical, abstract academic work. In my teaching, I use academic works, but I tend to use works that are ethnographies and that detail people’s lives. In my urban sociology class, all of my students have to go out into the community and work with people on the issues that we’re looking at, like poverty, homelessness, and crime. I send them out to organizations that I work with almost every day, including advocacy groups, so they learn about what’s actually going on, rather than just reading about it. In terms of scholarship, almost all of the work I do now has to do with consulting, helping to determine the most effective ways at getting homeless people into permanent housing. I don’t publish in sociology journals because that’s not what interests me. I want to be involved in decision-making and solving problems.