President Christina Paxson posed for a photo-op at the ribbon-cutting ceremony for Hope High School’s new library and media center—funded by a $150,000 donation from Brown University—while other schools in the Providence Public School District (PPSD) faced problems like crumbling lead paint, brown tap water, and asbestos. The library, like many of Brown’s efforts to aid PPSD, was a piecemeal victory for a school district grappling with systemic failure. Shiny new libraries alone will not save Providence schooling. As it turns out, the solution is much more costly for Brown: taxes.

Brown’s noncommercial properties are tax-exempt, a status the University is entitled to because, in theory, it provides the social benefit of education to local communities. In reality, however, Brown’s tax exemption robs public services of adequate funding without providing the purported benefits to Providence locals. Providence public schooling has been hit particularly hard: PPSD is a district in crisis, underperforming by every metric. Of its 24,000 students, only 10 and 14 percent are proficient in math and English Language Arts, respectively. Seventy-five percent graduate from high school within four years, less than both the statewide average of 84 percent and the national average of 86 percent. Absenteeism is common, with 48 percent of PPSD’s high school students missing 18 or more days of school throughout the year. The situation is so dire that the state has seized control of the district—a move that strips communities of color of political power, according to some.

When asked to identify PPSD’s number one problem, most members of the Providence School Board pointed to a lack of funds. Discretionary funding—money given to schools to be freely spent on auxiliary programs and supplies—is declining: In 2022, Providence public high schools were allocated $210.88 per pupil, a significant decrease from $308 per pupil in 2004. Funding allocated to special education decreased from $207.06 to $74.52 per pupil during the same period, hindering the growth of the 47 percent of PPSD students who have learning disabilities.

Moreover, local revenues consistently eclipse state contributions in Rhode Island public school budgets, making low-income students less likely to enjoy a well-funded education. Affluent towns draw from their considerable tax bases to fund their schools, while districts with fewer wealthy residents—like Providence, where the median income for families with children is almost $35,000 less than that of the state—struggle to keep up. In New Shoreham, the quaint summer destination known as Block Island, only 18 percent of students qualify for free or reduced lunch; the town’s public schools received $39,333 per student in 2020. In the same year, the students of PPSD, 88 percent of whom qualify for free or reduced lunch, received just $18,015 each.

Classical High School is arguably the crown jewel of Providence public schooling: The US News & World Report ranks it number one among Rhode Island public high schools and number 91 nationally. Students score in the 96th percentile on the SAT, and the school’s graduation rate is 97 percent. Nadia Heller, who graduated from Classical in 2020, reported that Brown admitted 10 of her grade’s approximately 270 students—a rate of admission she believes is substantially higher than those at other PPSD high schools (although official data is not available to the public).

Attending an institution like Classical is inaccessible to many; the price of success for Providence’s high-achieving public schools is the exclusion of marginalized students. The school’s unusually successful track record can be attributed to its competitive entrance exam. Critically, the test is only offered in English, despite the fact that 35 percent of PPSD students are learning English as a second language (ESL). As a result, less than 2 percent of Classical’s students were ESL learners in 2022. Relatedly, white students make up only 9 percent of PPSD students but 24 percent of Classical’s student body. Thus, the district’s occasional successes, like Classical, should not be used as evidence of its merits, but rather as a sign that it is rife with inequities. The basis of Brown’s tax exemption—that the University provides the benefit of education to local communities—evidently goes unfulfilled for large swaths of Providence’s youth.

As a financial powerhouse and paragon of higher education, Brown frequently avows its commitment to aiding the students of PPSD. In addition to financing the library renovation at Hope High School, the University announced in February that it would provide full financial aid to every PPSD student admitted to the Brown Pre-College Program. Brown also created the Fund for the Education of the Children of Providence in 2007, which pledged to raise $10 million for the district.

Many of the University’s efforts to support PPSD, however, have been either insufficient or unsuccessful. By the end of June 2020, 13 years after the Fund was established, Brown had raised only $1.9 million of its promised $10 million. To rectify this failure, the Brown Corporation authorized a designation of $8.1 million. Yet even with this pledge, PPSD reaps only $400,000 to $500,000 per year from the Fund—pocket change dwarfed by the University’s $6.5 billion endowment.

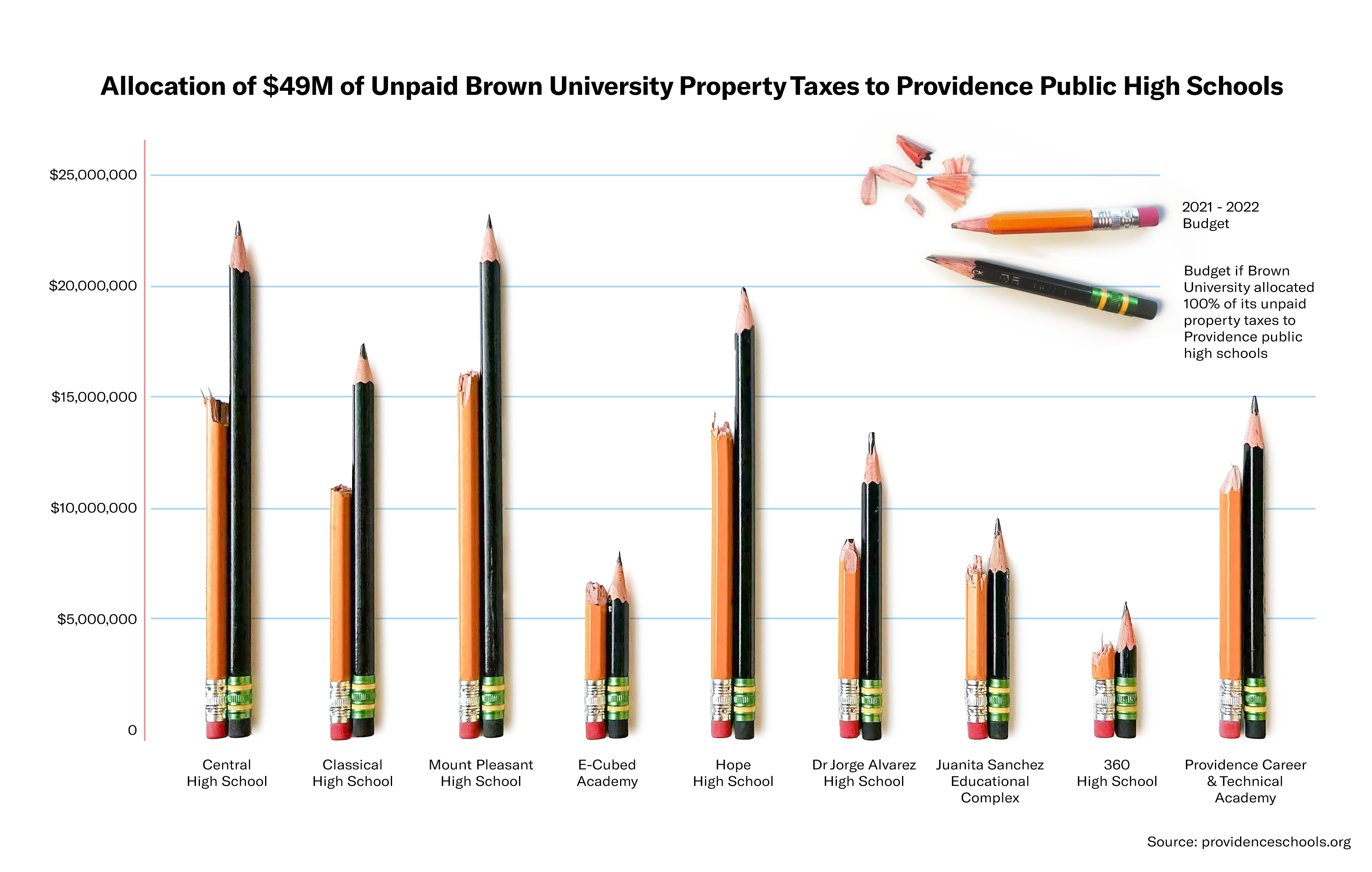

The insufficiency of Brown’s monetary contributions to PPSD is made especially apparent when one considers what the University should be paying. The University’s property is valued at $1.3 billion, a figure that would yield a whopping $49 million in property taxes. As part of the payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT) program, the state of Rhode Island—not Brown—reimburses Providence $13 million annually for the University’s tax-exempt status. Brown contributed an additional $6.5 million in voluntary payments in 2022, but that is just 13 percent of what it would pay in property taxes. All in all, Providence loses nearly $30 million each year as a result of Brown’s tax exemption.

That loss of funding has significant ramifications for public schools in Rhode Island, where property taxes make up 49 percent of total public school revenues, markedly more than the US average of 37 percent. Moreover, 97 percent of Rhode Island’s local public school revenue—derived from municipal sources rather than from the state—comes from property taxes, as compared to an average of 82 percent nationally. Property taxes are vital to public school funding everywhere, but their influence is particularly palpable in Providence.

To reduce the wide quality and achievement gaps between Providence schools, Brown should look to the examples set by universities that have attempted to rectify their unjust relationships with the cities they occupy. Yale University recently promised to donate an annual $10 million to New Haven for the next five years in addition to its existing PILOT commitments. New Hampshire state law compels Dartmouth College to go a step further, paying local property taxes on dorms, commercial buildings, and rental properties. Following these precedents, Brown must step up and either pay property taxes or increase its voluntary payments to a comparable sum.

We now reach a delicate moment in the story of Providence public schooling. As PPSD flounders, Brown continues to purchase Providence land—most recently 10 parcels in the Jewelry District—at a rapid clip, demolishing homes and local businesses in the process. The more land the University purchases, the less land there is to tax. If Brown fails to aid PPSD monetarily, its immense successes will come at the grave expense of local youth.