The death of Alexei Navalny on February 16, 2024 was equally shocking and unsurprising. Few expected Navalny’s confinement in an unusually strict Siberian penal colony to end happily, and his death spurred a dizzying set of tributes and memorials as supporters laid flowers at Russian embassies across the world. Within Russia, thousands of mourners braved government repression to pay their respects at his grave—many later ended up detained.

The West crowned Navalny the unquestioned leader of the Russian anti-Putin opposition for many reasons. He had been a nationally recognized politician since at least 2013, when he nearly won the mayorship of Moscow, and the anti-corruption exposés carried out under the auspices of his Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) successfully embarrassed the Putin regime at home and abroad. Moreover, Navalny’s willingness to return to Russia despite repeated assassination attempts won him a passionate following. Thus, after his death, Western news media was quick to refer to him as the opposition’s “brightest star” and the regime’s most “formidable opponent.” This idolization begs the question: If Navalny is gone, what is to become of the Russian opposition?

The answer is more easily supplied than most would expect. The Russian opposition will likely continue along exactly the same path as it trod before, tripping the same snares and making the same blunders. The reason for this admittedly pessimistic assessment is that Alexei Navalny was not the leader of the “Russian opposition” but merely the standard-bearer of its largest faction. In contrast to what outside observers might presume, Navalny showed little interest in merging his faction with others to present a united front. His successors are gearing up to repeat the error.

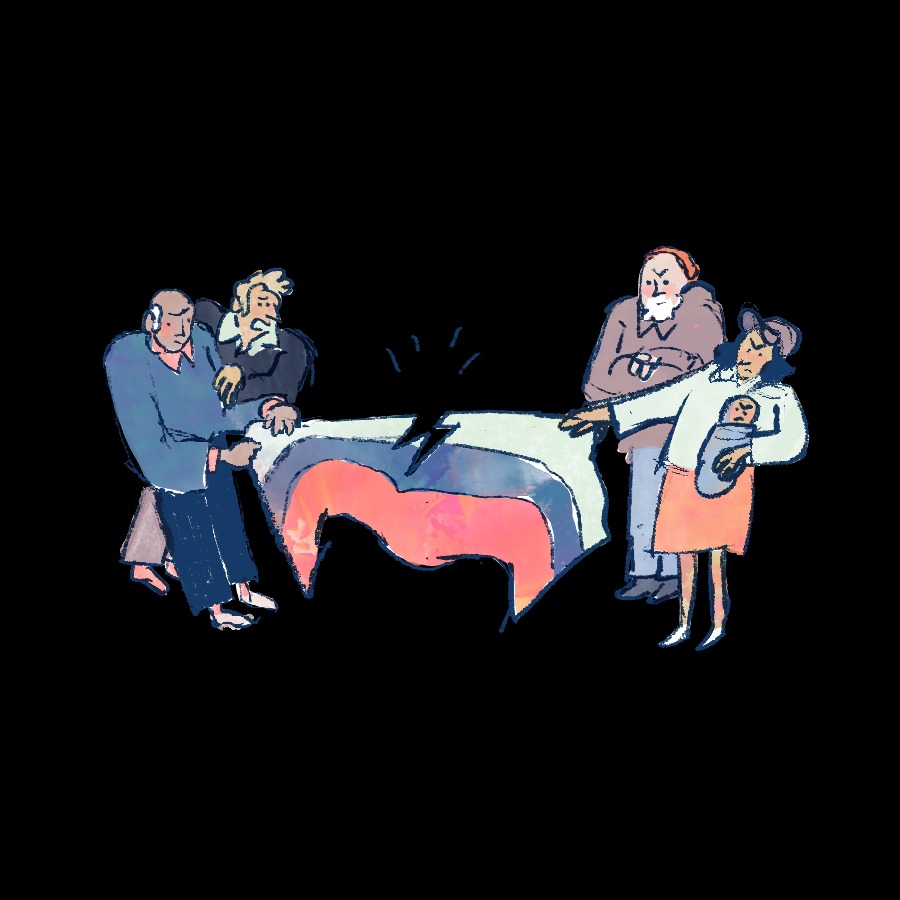

What are the factions of the Russian opposition, and what keeps them divided? The three largest are those headed by Navalny (and now his wife Yulia Navalnaya), Maxim Katz, and the tag team of Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Garry Kasparov. A survey of 2,088 signatories of the largest petition against the war in Ukraine found that 26.3 percent supported Navalny as opposition leader, 21.7 percent supported Katz, and 13.8 percent supported Khodorkovsky and Kasparov, while 14.1 percent opted for “none of the above.”

The sharpest divide is between the Navalny and Katz camps. Katz, who now lives in Israel, got his start as Navalny’s lieutenant during the 2013 Moscow mayoral race. Though Navalny’s team was initially quite complimentary of Katz’s skills and talents, the two later fell out sharply. In 2016, Navalny referred to Katz as a “dishonest person and just a crook.” Katz replied that Navalny disliked the existence of an “alternative center of power” within the opposition—in other words, Navalny was more interested in leading the opposition than seeing it succeed.

These personal attacks set the stage for larger feuds on matters of policy. Prior to the 2024 Russian presidential election, Katz put forth the view that the opposition should unite around a shared slate of candidates rather than boycott the election or protest at polling stations. In response, Navalny, in a message from prison, told Katz to “go to hell,” and the chair of the FBK likewise instructed him to “stop selling pink unicorn snot.” Navalny’s organization instead encouraged Russians to pick and choose their votes carefully, boycotting the most obviously rigged elections and coming out in force in unexpected, lower-stakes contests, such as those for the Yekaterinburg city legislature.

The last remaining faction, led by former oligarch Khodorkovsky and former World Chess Champion Kasparov, espouses an even stronger view against elections than the Navalny camp: no voting under any pretense. Khodorkovsky first made international headlines when he was sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2005 on politically motivated charges. Since his release in 2013, he has become an anti-Putin crusader, creating the Open Russia civil society organization—which was shut down by the Kremlin in 2021—and teaming up with Kasparov and his Free Russia Forum. Khodorkovsky’s relations with Navalny have also been strained: He implied in a 2017 interview that Navalny would become another Putin should he come to power, and reiterated Katz’s complaint that Navalny believes “there can only be [one] leader.” Immediately after Navalny’s death, Khodorkovsky was quick to renew the call for a big-tent opposition coalition and cast Navalny as the main obstacle to accomplishing it in the past.

If the only division within the Russian opposition was on the question of voting in elections, there would be serious hope of reconciliation. Unfortunately, this split is just one of many. Opposition supporters cannot agree on whether the invasion of Ukraine should be abandoned entirely or prosecuted to the full despite its initial inadvisability, as the anti-Putin, right-nationalist Roman Yuneman argues. Nor can they agree on the antecedent question of whether the 2014 invasion of Crimea was illegal or whether the peninsula should be returned. They are split evenly on whether a democratic Russia should permit the secession of ethnic-minority republics. There is not even consensus on whether or not the killing of pro-war propagandists is acceptable, with roughly 29 percent saying it ought to be. And all of these policy differences do not account for a definite left-right divide among opposition supporters, with roughly one-third describing themselves as firmly right-of-center and one-fifth as firmly left-of-center.

Some may have hoped that the death of Navalny would serve as a wake-up call for the remaining opposition leaders to put aside their personal and political differences, but initial indications have been far less than promising. Following Navalny’s death, Yulia Navalnaya has taken up his mantle as the “leader of the opposition.” Like her late husband, she has refused to build bridges with the disparate camps the Western media so readily marginalizes. For instance, on her personal X account, Navalnaya has trashed fellow opposition member Boris Nadezhdin for suggesting that people should be allowed to criticize Nalvany. Navalnaya can certainly be forgiven for an outburst in a time of grief, but such words do not build coalitions. The rancor between Katz and Navalny supporters has not lessened either, with Katz obliquely criticizing the latter group’s attitude of “learned helplessness” with respect to the most recent elections.

And if all of this was not enough, the Russian opposition has yet to confront its other fundamental problem: It is not popular. Though good polling is very difficult to conduct in Russia, a reputable independent pollster, Russian Field, found that, when offered a choice between Putin and “a worthy candidate of views similar to yourself,” 47 percent of voters opted for Putin. In other words, 47 percent preferred Putin over the candidate of their dreams. Additionally, 58 percent perceived Putin as the candidate “most aligned with their interests.” Though 58 percent may not be the 87 percent that Putin received in the sham presidential election, it still represents a larger popular majority than any US president has received since 1984. If there was a genuine groundswell of popular support against Putin, the fact that the opposition spends nearly as much ammunition on itself as it does on Putin would not be fatal. But that is not the case, and every barb hurled from one oppositionist to another only makes the Putin regime more secure.

To present a serious alternative to Putin, the Russian opposition must put aside its childish factionalism and unite around a big-tent platform centering on policies that have near-universal support, such as a crackdown on endemic corruption. Fighting about thorny issues can wait until after Putin is overthrown. Some may argue that the lack of a detailed platform serves as a barrier to popular support, but efforts to replace Putin will fail if individual opposition constituencies prioritize their own pet issues. Factional standard-bearers like Navalnaya, Katz, Khodorkovsky, and Kasparov should recognize that a movement as broad as theirs cannot have one leader and would prosper if they worked together to present a united front.

Navalny’s personal strength, willingness to make the ultimate sacrifice for his beliefs, and faith that the Putin regime will someday “collapse and crumble” should always be cornerstones of the opposition movement. But the bitter personal antipathies and petty quarrels that characterized his time as so-called “opposition leader” are better left in the past. Otherwise, Russia’s liberal opposition is certain to die with him.