By Eli Motycka

It was by 19th century candlelight, in then-President Elisha Andrews’ office after nightfall, that the first women were educated at Brown University. The movement that started with six high-achieving local high school students, brought to Brown at Andrews’ personal invitation, has grown beyond recognition to redefine the intellectual architecture and values of the University itself.

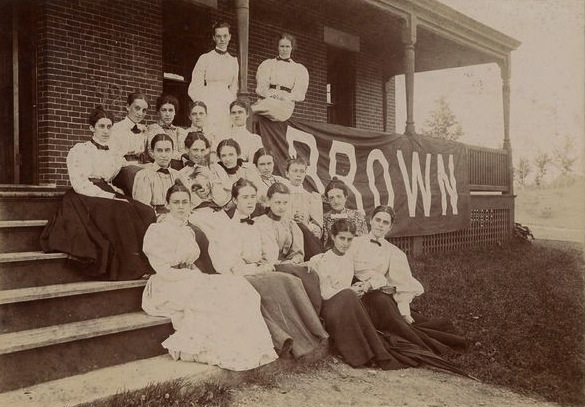

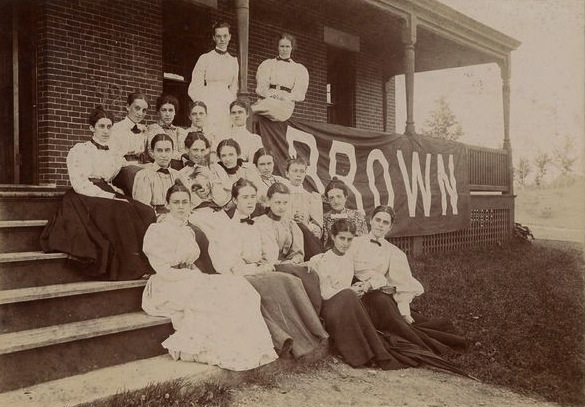

Enrolled in Brown’s Women’s College, their numbers grew quickly — 200 women were enrolled by 1898, 500 by the 1920s — as did their resources and opportunities. Through both World Wars and into the second half of the 20th century, female involvement grew to rival that of men. The Women’s College became Pembroke College in 1928, single-sex classes had almost disappeared by the 1940s, and 1200 women were enrolled by 1970. The next year, Pembroke merged with the University to turn the two schools into one coed institution.

This change was facilitated by student activism around social norms. By the 1960s, Pembroke students had begun to resent their isolation, and in a decade of social upheaval that was felt strongly on college campuses, challenged gender-based divisions. However, this fight was not only directed at Brown’s patriarchal policies — it was forced to deal with Pembroke as well. Even as feminist activism fomented on College Hill, the Pembroke administration retained antiquated ideas about the purpose of a college education. Vestiges of a bygone era were everywhere: first-year students were required to be photographed in their underwear to evaluate posture; and a female-only “freshman fundamentals” class covered material like etiquette and exercises to alleviate menstrual periods.

These stubborn relics highlighted the gap between a progressive student body and administrators from older generations. But the 1960s wave of social activism hit Pembroke and decimated many of its institutions: Pembroke’s student government merged with Brown’s in 1967; most curfews were abolished by 1968; and coed housing began in 1969. When the Pembroke Study Committee drafted its merger proposal in the spring of 1970, Pembroke only claimed several administrative entities as separate from Brown.

While a fundamental pillar of the merger’s agenda was to preserve the institutions that Pembroke offered women, a lag in female leadership at Brown followed the unification of the two universities. Female leadership fell sharply in the coed student body, as did first-year female students’ academic performance in comparison to both their high-school grades and the performance of their male peers. Additionally, only half of Pembroke’s 22 administrators made the move to Brown. To combat this decline, administrators, professors, students and alumnae formed the Working Group on the Status of Women to provide female students the resources at Brown that were previously offered by Pembroke. The construction of the Sarah Doyle Women’s Center in 1974 was the fruit of this union: an on-campus space that was founded for women’s studies and today supports student groups that concern women, gender and sexuality.

That same year, anthropology professor Louise Lamphere launched a legal battle with the University regarding its hiring policies towards women. Lamphere — the first professor to teach women’s studies classes at Brown — was denied tenure and notified too late to allow for appeal. Several female faculty members joined Lamphere in 1976 to file a class action lawsuit against the University. Lamphere’s campaign got results: In the fall of 1977 Brown adopted the Lamphere Consent Decree, which mandated clear criteria for tenure decisions, transparent salary information within departments and a committee to review certain offers of tenure. The Lamphere decision helped improve the representation of women in academic positions from 10 percent in 1977 to 23 percent in 1991. Today, Lamphere describes her decision to fight the university on the subject of her tenure as her “squeaky wheel” moment: the instant in which she decided to not be a silent cog in the machinery that had excluded women from these posts in the past. Her fight for equality within Brown’s institutional framework shows that faculty activism has shaped Brown’s institutional structure alongside student calls for change.

Brown solidified its commitment to female representation with the founding of the Pembroke Center. The organization soon became the crux of discussions of gender and sexuality at Brown. The Center sponsors an undergraduate concentration, now known as Gender and Sexuality Studies, and publishes “Differences,” a journal that addresses how “categories of difference” operate within culture.

In the same way that the Pembroke Center and the Sarah Doyle Women’s Center have adapted to the current frontiers of gender and sexual equality, today’s activism fits today’s needs. Deborah Weinstein, the director of Gender and Sexuality Studies at Brown, cites student discussion and scholarship in the classroom as a form of activism, challenging the way gender and sexuality function in society. A far cry from a handful of women engaging in candlelit study, Brown continues to thrive as the beneficiary of the legacy of Pembroke and the women’s movement at Brown.