A curious David-against-Goliath story is unfolding in disputed Southeast Asian waters. In late September, the small nation of Timor-Leste achieved a small but important victory when a UN Conciliation Commission declared that the Pacific country in the Indonesian archipelago could require Australia to negotiate a maritime boundary dispute over a territory rich in valuable oil and gas reserves. The announcement was partly the result of an increasingly assertive attempt at geopolitical repositioning by a country long known for two things: protracted violence and a pioneer model of UN trusteeship that paved the way for its independence in 2002.

Under Indonesian occupation from 1975 to 1999, Timor-Leste was the site of widespread human rights violations and lost nearly a third of its population – some 200,000 people – to armed conflict and starvation. It was only the resignation of Indonesia’s longtime ruler Suharto in 1998 that created the impetus for a referendum the following year. Timor-Leste’s 450,000 voters overwhelmingly chose independence over increased autonomy within Indonesia. However, violence erupted between Indonesian-backed anti-independence militias and their pro-independence counterparts, leading to the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people and ultimately the deployment of a UN-backed multinational peacekeeping force under Australian command.

The UN quickly embarked on a large-scale humanitarian intervention and created an interim government – the UN Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET). UNTAET ran the country for almost three years and pursued an ambitious nation-building program meant to revitalize the largely collapsed state, installing vital institutions of governance and rebuilding infrastructure, most of which had been destroyed by the post-referendum violence. The resulting peace, albeit tenuous, allowed for independence talks with Indonesia to continue. In May 2002, UNTAET handed over much of its administration to democratically elected Timorese leaders.

Fourteen years on, Timor-Leste has almost quadrupled its GDP, reached a middling score on the Human Development Index, and, most recently, topped Southeast Asia’s Democracy Index. Against this background, the UN intervention in Timor-Leste has become somewhat of a posterchild in using multidimensional peacekeeping – the deployment of both soldiers and large contingents of civilian staff to establish peace in conflict-ridden settings by monitoring elections and building functional, accountable institutions.

But the UN mission has not been without critics. Especially in its early stages, the operation suffered from coordination problems and struggled to include both Timorese leaders and the public in its decision-making process. The intervention struggled to build an effective judiciary, partly due to the fact that there were barely any qualified personnel left in the country. Stability has also remained shaky. In 2006, Timorese citizens disillusioned about the country’s development since independence took to the streets to protest poor living conditions and persisting discrimination. The protests spiraled into to a three-month period of violence that displaced about 150,000 Timorese, leading many to question the UN’s claims of success.

In light of these setbacks, the country’s leaders have sought new approaches to tackle remaining issues. Timor-Leste was a founding member of the g7+ group, an intergovernmental organization that brings together post-conflict states to address the development issues facing their countries. Additionally, in 2011, the government announced a 30-year Strategic Development Plan focused on ramping up human capital and infrastructure, as well as on designing a judicial system that integrates the country’s customary law, which is currently practiced in unofficial parallel courts throughout the country.

But despite many advances, serious challenges remain: Less than half of the country’s homes have electricity and 41 percent of the population remains below the poverty line. Additionally, both the state and the economy depend almost exclusively on income from drilling oil in the Timor Sea. Oil revenues account for about 90 percent of both the annual state budget and annual GDP. Recent estimates show that the Petroleum Fund, a sovereign wealth fund that pools Timor-Leste’s oil revenues and currently stands at $16.5 billion, could be completely depleted by 2025, undercutting the country’s ambitious development plans. As a result, Timorese leaders are scrambling to find new revenue sources, and the $40 billion in untapped oil reserves, which are at stake in the current boundary dispute with Australia, could very well determine whether the country can stay on course or will descend back into pre-independence poverty.

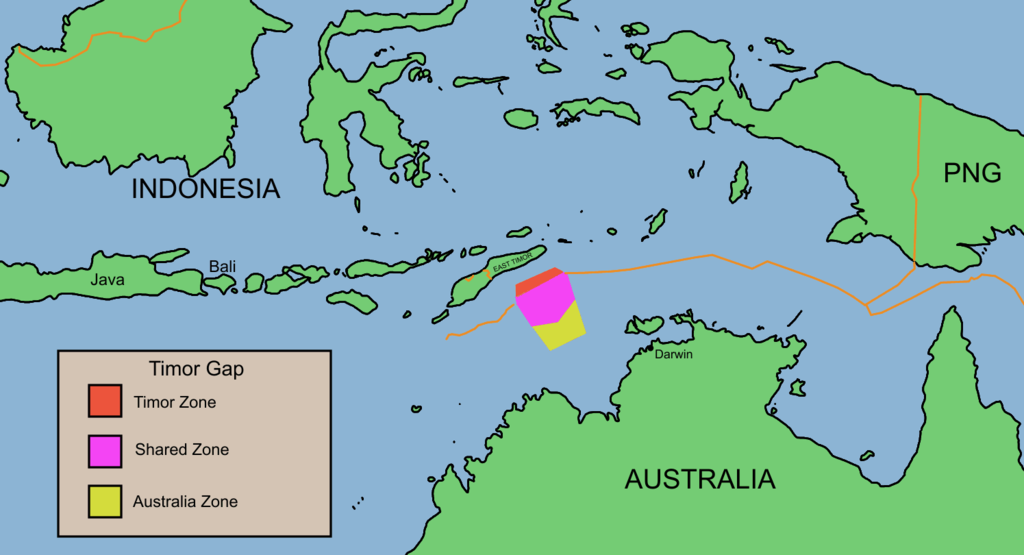

The dispute with Australia goes back to the region’s complex colonial and legal past. In 1972, when Timor-Leste was still a Portuguese colony, Australia signed a maritime boundary treaty with Indonesia. The most common principle under international law is to draw a boundary along the median line – the line equidistant from the two shores. Instead, the Australia-Indonesia agreement used the edge of the Australian continental shelf to determine the boundary. While admissible under international law, this was an unusually good deal for Australia. Since its seabed extends far north, the arrangement brought the boundary much nearer to the Timorese shore and allowed Australia to exploit resources in the Timor Sea far beyond the median line. Despite the agreement, Portugal insisted on using a median line, leaving the boundary – and subsequent oil claims – unresolved.

When Indonesia invaded Timor-Leste in 1975, Australia was the first country to recognize the annexation, hoping that its favorable arrangement with Indonesia would be extended to Timor-Leste. However, Australia and Indonesia struggled to come to an agreement and, rather than setting up a clear boundary, created a zone of economic cooperation and equal resource-sharing in the Timor Sea.

This Indonesian-Australian treaty became void upon Timor-Leste’s independence in 2002, prompting a new round of negotiations, this time between Australia and a newly independent Timorese government. In anticipation of these negotiations, Australia withdrew from an optional protocol of the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The optional protocol puts maritime disputes between member countries under the jurisdiction of an international tribunal in The Hague, whose rulings are binding.

Because of this withdrawal, the negotiations between Australia and Timor-Leste were purely bilateral and Australia was able to exploit its newly independent neighbor’s dire need for quick oil revenues to push for a favorable agreement. In some respects, the resulting treaties shifted the balance somewhat in Timor-Leste’s favor, granting it 90 percent of the revenues from the shared economic zone that had been established by Australia and Indonesia. However, much of the Greater Sunrise field, a particularly promising area of exploration in the Timor Sea, was allocated to Australia. Had the median line principle been used, the area would have fallen squarely under Timor-Leste’s control. When Timor-Leste requested a permanent solution based on the median line principle, Australia rejected the proposal and imposed a 50-year freeze on renewed negotiations in a 2006 treaty known as Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS). This meant that the issue could not be legally revisited for half a century.

For Australia, this means the issue is settled – at least until the 2050s. From the shores of Timor-Leste, however, things look very different. Already feeling they got the lesser end of the deal, Timorese leaders were further incensed to learn that, back in 2004, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service had wiretapped the Timorese government’s cabinet rooms, where critical discussions on the CMATS treaty took place. Timor-Leste argues that this unrightfully gave Australia the upper hand in the negotiations and that it invalidates the CMATS treaty and its 50-year ban on renegotiations.

For Australia, this means the issue is settled – at least until the 2050s. From the shores of Timor-Leste, however, things look very different. Already feeling they got the lesser end of the deal, Timorese leaders were further incensed to learn that, back in 2004, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service had wiretapped the Timorese government’s cabinet rooms, where critical discussions on the CMATS treaty took place. Timor-Leste argues that this unrightfully gave Australia the upper hand in the negotiations and that it invalidates the CMATS treaty and its 50-year ban on renegotiations.

Australia was initially able to resist renewed talks because its withdrawal from the optional protocol UNCLOS means that international tribunals do not have jurisdiction to hear any maritime disputes involving Australia. However, since both countries are still signatories of UNCLOS, Timor-Leste was able to initiate compulsory conciliation proceedings mediated by the UN. The revelations of the bugging scandal and the fact that Timor-Leste’s economic future could depend on the negotiations may tip the scales somewhat in its favor. But unlike the rulings of an international tribunal, the UN’s recommendations under this procedure will not be binding.

Yet while Australia can simply dismiss any solution deemed counter to its interests, the country could still draw fire for behaving inconsistently. First, it would go against Australia’s own commitment to assist Timor-Leste’s development – it currently gives the country double the amount of its next-largest aid provider. Second, Australia has strongly condemned China for its refusal to accept the ruling of an international court in The Hague in a similar dispute in the South China Sea. However, the South China Sea case differs somewhat, since China’s territorial claims in the area relied on its historical importance in the region – a narrative that the Hague court ruled lacking any legal basis. Australia’s position, by contrast, relies on treaties and geographical principles admissible under international law. Nonetheless, the background of the dispute, as well as the fact that the Greater Sunrise field is just a fraction of the estimated Australian oil reserve of 233 billion barrels means it risks being painted as a bully of developing nations. Indeed, Timor-Leste could use this narrative to garner support from the international community and pressure Australia into a new agreement.

This is not to suggest that Timor-Leste is entirely without fault. The strategy behind the Australian concessions – complete with lobbying trips by Timorese leaders to the United States – conveniently distracts from important domestic problems. Chief among them is the country’s inability so far to develop a credible strategy for moving away from its extreme dependence on limited oil revenues. Despite the focus on human capital and sustainable development made in the government’s 30-year development plan in 2011, current budgeting suggests a different focus: 45 percent of total expenditures are allocated for infrastructure programs – especially large-scale oil infrastructure projects. Meanwhile, only nine percent is spent on education and two percent each on agriculture and the country’s seriously underdeveloped judiciary.

Critics point out that this focus may hurt the country’s ability to diversify economically. Yet the rapidly depleting Petroleum Fund and its associated income means the government is caught in a difficult bind: Rather than investing in the country’s long-term economic future, it is gambling that redrawing boundary lines will generate revenues and offset the predicted losses from current reserves.

Tasi Mane, a corridor of petroleum and gas infrastructure, is one such opportunity to harness potential future oil from the disputed Greater Sunrise area. However, this strategy comes at the price of cutbacks in other crucial areas. The 2016 budget stipulates further decreases in education by 8.4 percent, healthcare by 17.4 percent, and agriculture by 29.6 percent. The government claims that these cutbacks are temporary and will be reversed by 2020, when the country’s developmental capacity subsequently increases. Yet out of the 10,000 jobs expected to be created by the project, only 200 to 350 will be permanent positions. There is no guarantee that these positions will even be reserved for Timorese workers, let alone if the country even has enough skilled native workers who fit the bill. Cuts in education spending will not help Timor-Leste rectify such long-term issues. Moreover, experts estimate that it would take five years for the project to generate any revenues, at which point the declining income from Timor-Leste’s current reserves could lead to serious funding shortages.

But betting on the future availability of untapped oil reserves is not an inherently doomed strategy. For instance, the country could bridge looming funding shortages by borrowing more from international institutions such as the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank, while simultaneously ensuring that any infrastructure projects actually strengthen its domestic economy and workforce. However, the government should not lose sight of the longer-term challenge of weaning itself off its dependence on oil revenue. Channeling investment into underdeveloped sectors like agriculture would be a good way to start – 70 percent of Timorese rely on some form of farming activity or another. Likewise, improvements for both human capital training and the judiciary system should be given more weight.

The ongoing conciliation commission, which is set to produce a recommendation no later than April 2017, will determine the likelihood of those potential changes. In the meantime, however, the maritime boundary dispute and Timor-Leste’s domestic challenges both present an opportunity to reflect on regional successes and failures. Timor-Leste’s fragility and Australia’s actions, especially its wiretapping, are causes for concern. The power dynamic at play between these two countries becomes especially troubling given that Australia has knowingly sought to weaken the strength of international law so that it can conduct its business with Timor-Leste through bilateral negotiations, inherently giving the much stronger country a distinct advantage. Given Timor-Leste’s remarkable turnaround since its independence, the stakes for the results of the maritime boundary negotiations could not be higher. The success of this young country may hang in the balance, as well as the ability of larger developed nations like Australia to have free reign in their treatment of weaker neighbors. The outcome of the negotiations may ultimately remain unresolved beyond next spring, and even if Timor-Leste is successful, it still has a long road ahead of it to rebuild stability as a nation. But regardless of who ends up with control over the disputed oil, this conflict has important ramifications on international power dynamics beyond the Timor Sea.