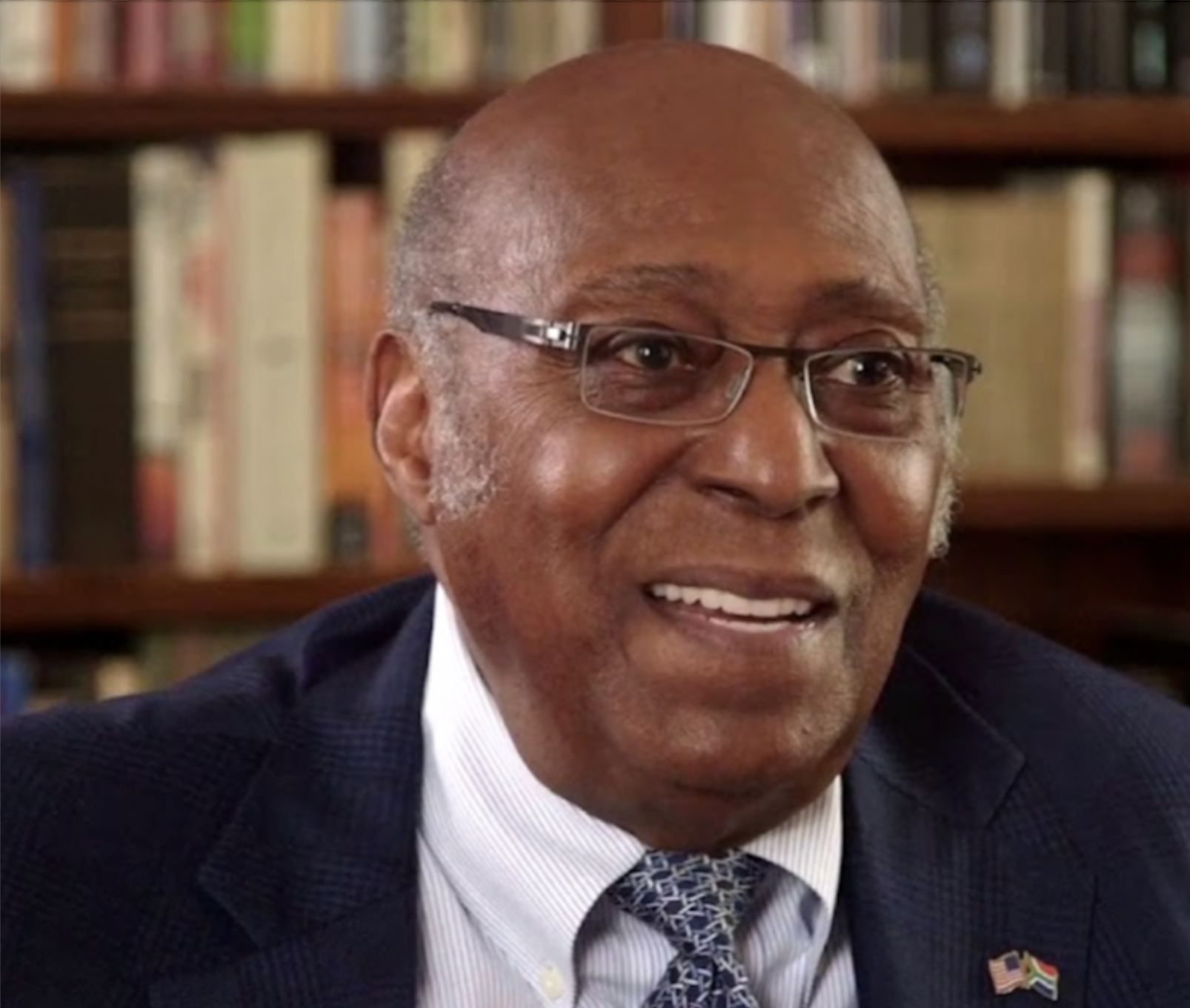

Charles V. Hamilton is the Wallace S. Sayre Professor Emeritus of Political Science and Government at Columbia University. He has produced some of the most influential scholarship on race and American politics in the twentieth century, including his most famous book, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, which was written with the late Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) in 1967 and coined the phrase “institutional racism.” Hamilton has also authored The Black Preacher in America (1972); Bench and the Ballot: Southern Federal Judges and Black Voters (1973); Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.: The Political Biography of an American Dilemma (1991); and The Dual Agenda: Race and the Social Welfare Policies of Civil Rights Organizations (1998), which he co-authored with his late wife Dona Cooper Hamilton.

Hamilton was born in Muskogee, Oklahoma, in 1929 at the height of Jim Crow and the Great Depression. He and his family moved to Chicago in 1935, where he went on to receive a BA from Roosevelt University, JD from Loyola University, and PhD in Political Science from the University of Chicago. Hamilton taught at Tuskegee Institute and held faculty positions at Rutgers University, Lincoln University (in Pennsylvania), and Roosevelt University before joining the Columbia University faculty in 1969 and retiring in 1998. He served in the United States military the same year it was desegregated by President Harry Truman. Hamilton recently celebrated his 92nd birthday.

Sam Kolitch: You grew up in Chicago and attended Roosevelt University, which was regarded as a “hotbed of Chicago radicalism” at the time. Yet you later taught at Tuskegee Institute, a historically Black college shaped by the conservative vision of Booker T. Washington. How did the radical ideas of your upbringing mesh with Tuskegee’s conservatism?

Charles V. Hamilton: I got fired from Tuskegee because I was teaching the kids how to contact Congress and march and protest. Tuskegee said to me, “You don’t belong here.” I was very angry at them. In fact, I was very disturbed because I really wanted to stay there. It was an all-Black college, was very well known, had very good students, and that is where I wanted to teach and to write. But I did not belong. They did not want a professor who was an activist; they wanted one who only taught. “You are here to teach—not to preach, not to act.”

The one good thing I took out of Tuskegee was my daughter. She was born there. Later on, Tuskegee gave me an honorary degree.

SK: Did you always want to combine teaching with activism?

CVH: Absolutely. I couldn’t teach if I couldn’t act. All of my teaching stems not only from my studies, reading books, and talking to students, but from acting it out. When I had the students in Tuskegee writing to Congress and marching in protest movements, I thought that was a good way to teach them how the system worked. What’s the good in teaching them how to act if they don’t really act? I would say [to my students], “Eventually you are going to be mayor of this town or governor of this state because you got it nonviolently and legally.” If you get something legally, you have made a major step toward eradicating racism. You got a complaint? March. If they hit you, hit them back.

SK: As a result of your activism in the ’50s and ’60s, you were surveilled by the government. How did that come about?

CVH: The FBI came to my house and asked if they could tap my phones. I said, “Yes, of course. Nothing to hide.” They had gotten “information” that I might be a communist. I said, “Oh my goodness, goodness, goodness.” One FBI agent went inside and did something to the phone. Another one went outside and put something on the telephone—and I decided to go outside to help him. (Laughs.)

SK: 54 years ago, you coined the phrase “institutional racism” in Black Power, your book with Stokely Carmichael, which is still taught on college campuses to this day. Did you expect that the then-radical ideas espoused in the book would be widely believed today?

CVH: Yes, because we were talking about organizing nonviolently: “March! File court cases!” We were not calling for burning up this, burning up that, or even boycotting, which was [Martin Luther] King’s thing.

SK: On page 44 of Black Power, you write—

CVH: “Before a group can enter the open society, it must first close ranks.” That line is my most important contribution to American history.

SK: In your words, that line “was an honest recognition that for any group…to become a respected, effective player in the American political system, cohesive organization was crucial.” What indicates whether a democracy can enable that?

CVH: A democracy, as I define it, is a system whereby the people who are to be governed should have the right to determine who performs that governing. It is not an autocracy, not a monocracy, not a communist society. If people are to be governed, then they should decide who performs that governing task. And they should [achieve that] through the process of voting. Then you have a democratic process for legitimizing change.

SK: With that definition in mind, what is your advice to student activists?

CVH: Participate. Participate in something outside of lectures, the classroom, and term papers. See how the system works. You have to be involved in something bigger than your language. But let’s not move too quickly because that’s a real jam. Tiptoeing toward change [is best].

SK: But do you sympathize with the younger generation’s idealism and desire for things to change quickly?

CVH: Too much. (Laughs.) I gain my sustenance from young people. It was young people who protected me every time I got fired from a job.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.