As of late, rising rent has increasingly plagued large cities across the United States. Homeownership is a crucial aspect of building personal wealth and improving one’s socioeconomic status, but it has become unattainable for millions of Americans. This housing shortage has had a particularly pronounced impact on New York City. Regular New Yorkers are struggling to find places to live, and competition for apartments is stiff. Overpaying for a smaller space has long been accepted as the necessary price for living in the city that never sleeps. However, newly constructed buildings waste the already limited space in the city, and some even have fewer apartments than the structures they replace. In the wake of “Covid-deals” on apartments, deep-seated issues that have plagued the housing market are coming to a head. Coupled with inflation, interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve, and rents that seem to reach record highs every month, a foreboding picture is painted of the New York property market.

Despite New York’s recent attempts to increase affordable housing, the opposite has happened. When Covid-19 hit the city in the spring of 2020, a mass exodus artificially alleviated the ever-growing housing crisis. However, with the city in recovery, people are flocking back, causing rents to rise as competition for units increases. Former New York Mayor Bill de Blasio made the housing crisis a priority of his administration, particularly by pushing inclusionary zoning. The policy, meant to encourage the building of affordable housing in expensive areas, authorizes developers to build 33 percent more square footage than typically allowed in return for setting aside 20 percent of the units to be rented out at a lower rate. Unfortunately, the high cost of subsidizing such housing deters small or midsize project developers from taking advantage of the policy. Thus, inclusionary zoning from mid-2005 to 2013 resulted in fewer than 3,000 new units. To remedy this lack of implementation de Blasio attempted to make the policy mandatory, a move that received pushback due to fears that it would prevent low to middle-income areas from attracting developers.

Similar proposals that aimed to increase housing, like Governor Kathy Hochul’s plan to lift restrictions on residential density, died in the legislature due to public pushback. After the plan was announced, local groups advocated against the bill as they feared it would only lead to more buildings like the ones on billionaires’ row. The luxury buildings house apartments that sell for a median price of $9.8 million. Simply reforming laws that limit the floor-to-area ratio of buildings does not guarantee that developers will build much-needed housing that the average New Yorker can afford. Even to rent, the prices of apartments in these towering structures are far from what is feasible for those most impacted by skyrocketing rents. By focusing on breaking records with exorbitantly expensive apartments, such as the one bought by the billionaire hedge-fund manager Ken Griffin for $238 million, builders fail to solve the increasingly pressing issues at hand.

New York City has faced housing market struggles for over half a century, ever since city planners warned in 1959 that the population would swell to 55 million. Laws were passed to limit the size of buildings and the number of people living in them to prevent this rapid growth. Thus, the massive rezoning was in response to fears of overcrowding and the subsequent strain on municipal services this would cause. An end to these archaic laws would be a step in the right direction for NYC’s crippled housing market, as it would enable the construction of higher-density residences that can be offered at lower prices.

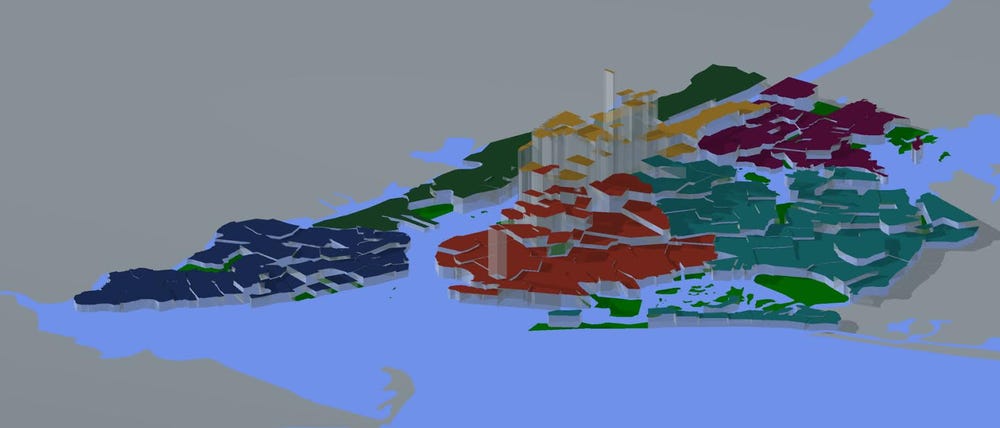

Put simply, in its current state, New York cannot keep up with the rampant population growth it has experienced in recent years. Building on de Blasio’s plans, the new mayor, Eric Adams, and the New York City Council are investing $32 billion in affordable housing over the next 10 years. Developers and preservationists will get $22 billion, and the Public Housing Preservation Trust will use the remaining $10 billion to renovate NYC Housing Authority units. Additionally, the Adams administration has adopted a three-pronged approach affectionately named the “City of Yes” proposal, which seeks to streamline the production of affordable housing across the five boroughs. First, the rules that formerly only allowed senior housing to be built higher and with more units will apply to all affordable housing developments. Second, to significantly reduce costs, affordable structures will no longer be required to build underground and street-level garages. Finally, lawmakers will relax density requirements to provide the market with much-needed studio apartments. Regrettably, these changes are not set to be introduced until early 2024 and are slated to face political opposition.

While Mayor Adams has followed in de Blasio’s footsteps in making housing a priority, passing the measures necessary to combat the ongoing crisis has proven to be complicated. In 2022 alone, state lawmakers quashed at least four proposals to boost housing. Despite state lawmakers’ attempts to devise solutions for the housing crisis, well-funded preservation groups and local advocates are able to lobby in support of their often anti-housing-construction interests. Historically, stringent anti-development activists have succeeded, and politicians even placated them with zoning amendments restricting growth. To avoid opposition from these groups, Adams needs to form an effective political coalition to push the measures through amid pressure.

In an increasingly unaffordable housing market, what options are available for a new college graduate, a young couple, or a family struggling to make ends meet? With space at an extreme premium, is New York becoming a place exclusively for the super wealthy and those lucky enough to be their offspring? The days of $800 rent are over. The median price of a condo is $1.6 million, and the median price of a one-bedroom to rent is $2,106, a 12.1 percent increase from October 2021. But according to the New York Census Bureau, the median household income in the city was $67,046 in 2020. The disparity here is glaring. It exposes the uncomfortable reality that many of those who choose to stay in the city will continue to spend the majority of their paycheck on rent.

To make matters worse, the Federal Reserve has hiked the federal funds rate by 0.75 percent to combat inflation. Set by the Federal Open Market Committee, this influential rate determines how much commercial banks must pay to borrow other banks’ excess reserves overnight. In general, the rate is a tool to promote employment but also rein in inflation. Its increase reflects a tumbling stock market amid a drop in investment and declining stock prices. The federal funds rate can influence economic growth as lower financing costs can encourage borrowing and investing. A higher rate means that there is less economic activity of that nature. Although the federal funds rate is independent of mortgage rates and instead depends primarily on the 10-year treasury yield, the two have experienced similar rises. This increase is because lenders set their rates based on the prime lending rate, which is closely related to the federal funds rate, and is charged to the most credit-worthy borrowers. By increasing prime lending rates, mortgage rates also rise in turn, putting potential homeowners in a precarious position. With mortgages at their highest since 2008, the current situation offers a grim prognosis for those who hope to move up the property ladder.

The New York housing market is struggling to accommodate the continuous stream of people moving into the city. Without specific housing production goals, the few policies in place cannot fix the issue. The panic gripping the housing market is a glaring indictment of the failures of local politicians who cannot agree on feasible solutions. As people continue to move to New York, there seems to be no end in sight for a crisis where supply continuously fails to meet demand.