The precedent-defying Supreme Court case Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Clinic has reignited a conversation about sex education policy. With abortion made illegal in many states accross the nation, many have argued that American teens need more comprehensive and accurate sex education to reduce teen pregnancy. This perspective, along with traditional sex education curricula more generally, unfairly places the onus on young women to control their own behavior to avoid becoming pregnant. When comparing sex education practices and tactics, the debate usually surrounds their effectiveness, referring to how they impact the rate of teen pregnancy and spread of sexually transmitted diseases. But this is a missed opportunity: The commonly accepted sex education framework should not only be aimed at reducing the “sin” of teen pregnancy, but also at eliminating other “sins,” specifically sexual assault and homophobia.

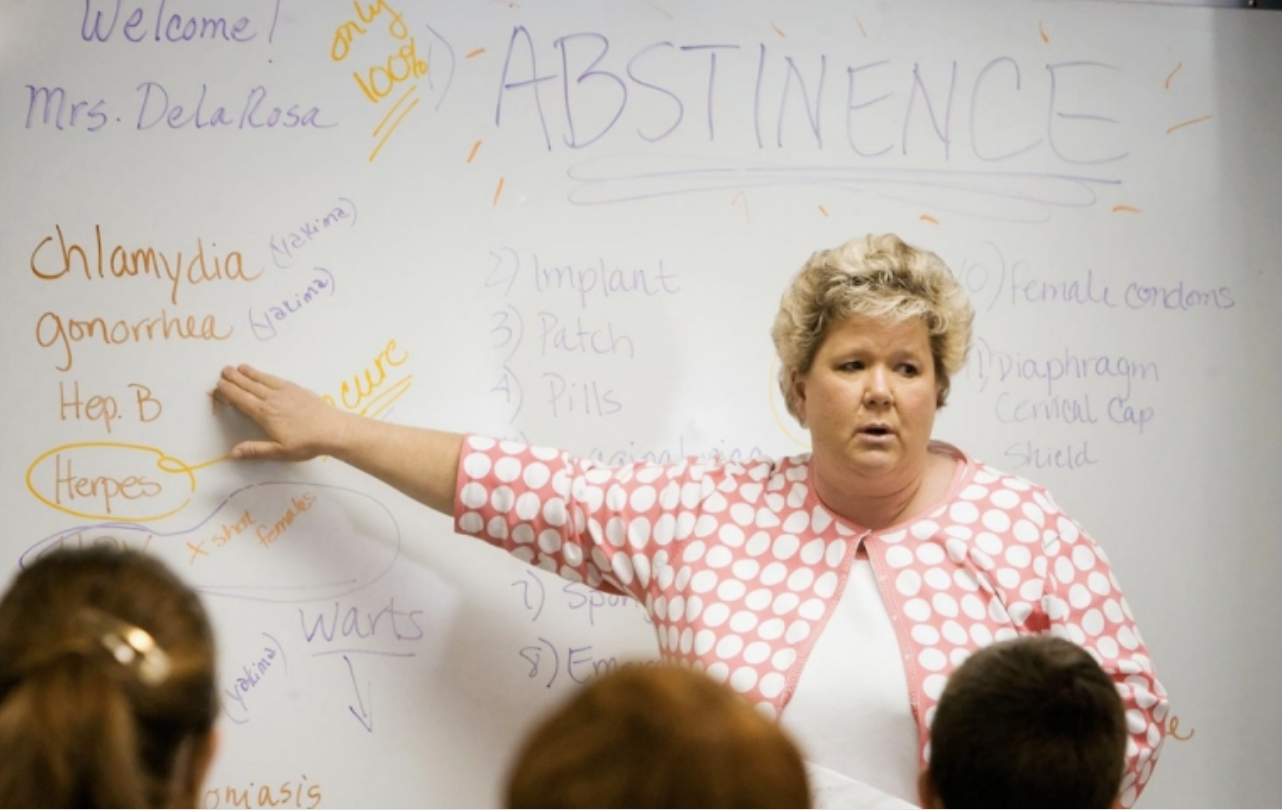

Because there are no federal regulations regarding what should be taught to students in sex education classes, there is great variation from state to state and district to district. Many schools still teach abstinence-only sex education, even though this approach is unpopular and has been proven ineffective. The lack of standardization also creates disparities in what is taught between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds. When districts have the ability to decide for themselves what to teach, the comprehensiveness of sex education is often associated with the wealth of the school district. Schools with larger budgets have more money to devote to sex education, leading students at different schools to have unequal access to accurate information about their own health.

Sex education also varies by gender. Girls are more likely to be taught to wait until marriage to have sex, while male students are more likely to be taught about birth control methods. Currently, only 39 states have a requirement for schools to teach any form of sex education. Additionally, just 43 percent of high schools and 18 percent of middle schools across the nation teach the key topics in sex education identified by the CDC. To mend these discrepancies, every state must explicitly require sex education in public schools, standardize the curricula across districts, and adjust their standards to specifically include sexual assault prevention and identity affirmation in sex education curricula.

Sex education in the United States needs to be based on truly comprehensive guidelines. The National Sexual Violence Resource Center bases their reccommendations on eight standards, which include comprehending core concepts, analyzing influences, accessing information, demonstrating interpersonal communication, making decisions, setting goals, practicing self-management, and advocating for oneself. These standards are applied to seven key topics: anatomy and physiology, puberty and adolescent development, identity, pregnancy and reproduction, sexually transmitted diseases and HIV, personal safety, and healthy relationships. The NSVRC’s recommendations should serve as the basis for sex education nationwide, as they first and foremost prioritize students’ sexual autonomy above all. They also cover the prevention of pregnancy and the spread of STIs—but these are just two factors out of many. They thoroughly demonstrate how genuinely effective sex education relates to almost every facet of life.

Sex education classrooms should be places where all students’ identities are honored and accepted. Traditional sex education alienates LGBTQ+ students by ignoring their sexualities and gender identities. If these communities are mentioned at all within sex education classrooms, it is usually in the context of HIV/AIDS and other STIs. Currently, just 10 states require discussions of LGBTQ+ identities to be affirming and inclusive for all students. Six states, all located in the south, either prohibit discussions of these identities entirely or (quite often) connect them to the spread of STIs, thereby stigmatizing. Having respectful conversations about LGBTQ+ identities and relationships will both help queer students develop a more positive self-image and combat homophobia within a school’s general culture.

Students of all ages need to be taught the importance of consent. Currently, just nine states and the District of Columbia require consent to be talked about in sex education classrooms. Expanding this requirement to states across the country will both help young Americans practice consent in their current and future relationships and allow them to recognize any non-consensual relationships in their own life. Some argue that teaching sex education, and more specifically teaching consent, should be reserved for older students—but this ignores how impactful learning about consent can be for a young child who may be, or is at risk of, experiencing abuse.

Teaching consent and affirming sexual and gender identities may seem like separate issues, but they are in fact intimately related, especially with respect to the experiences of queer women and transgender people. According to the CDC’s National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, 44 percent of lesbians and 61 percent of bisexual women experience rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner, while 35 percent of heterosexual women experience these. Additionally, 47 percent of transgender people experience sexual assault. By teaching adolescents about consent and sexual and gender identities, we can protect these vulnerable populations from experiencing assault. Of bisexual women who survive rape, 48 percent experienced their first rape between the ages of 11 and 17. We do not have data on who the perpetrators of these assaults are, but they nonetheless make it clear how critical it is for consent and sexual violence prevention to be taught in middle and high school.

The goal of sex education should be to empower young students to learn about their own personhood and personal health. Now is the time to address the need for sex education reform, because in the wake of Dobbs teenagers need to gain back the autonomy that has been stripped from them by the Supreme Court. Students armed with accurate information will feel more confident about and capable of making personal decisions about their bodies. Additionally, centering conversations around consent and choice rather than blame will empower young women. The next generation of Americans are coming of age in a post-Roe era. States need to act now to show these young teenagers the power they hold.