In January, a Chinese Coast Guard ship harassed Filipino fishermen aboard the KEN-KEN, preventing them from working in part of the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Earlier in 2022, a Chinese fighter jet intercepted an Australian surveillance plane in international airspace over the South China Sea, releasing chaff containing fragments of aluminum into the Australian plane’s engines in what officials described as a “very dangerous” situation. In August, China fired 11 missiles over Taiwan, five of which landed within Japan’s EEZ. These are just some of the increasingly aggressive actions China has taken in an attempt to control the South China Sea, ignoring the 2016 ruling from the Permanent Court of Arbitration that determined China had “no legal basis” for its claims.

The United States, at least in principle, is committed to upholding international law and protecting the sovereignty of its allies in the region. As tensions between the United States and China rise, however, the ultimate goal of US foreign policy toward China has become less clear. In particular, politicians have struggled to reconcile the messaging strategy used abroad—where the United States aims to promote a free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP)—with the rhetoric it invokes domestically—where politicians often embrace a more protectionist and isolated worldview sometimes referred to as a “foreign policy for the middle class.” This contradiction, while driven by valid political concerns, is unnecessary and harmful to US interests. To succeed, the United States must reject the zero-sum logic of a binary choice between these two visions and instead work to integrate them into a unified and mutually reinforcing foreign policy.

The terminology of a free and open Indo-Pacific was originally introduced in 2006 by the late Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe. It entered the mainstream of American foreign policy during the Trump administration, when Secretary of State Mike Pompeo formalized it as the key framework for US engagement in the region. At its core, the free and open Indo-Pacific concept promotes a vision of mutual prosperity where “all countries prosper side by side as sovereign, independent states” and enjoy the benefits of “free, fair, and reciprocal trade, open investment environments, good governance, and freedom of the seas.” While perhaps led by the United States, this vision sees the United States as just one of many countries in the region—such as Japan, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, South Korea, and India—committed to working together to achieve shared prosperity.

The United States National Security Strategy, published by the Biden administration in October, 2022, identifies promoting “a free and open Indo-Pacific” as a “vital interest” that will “demand more of the United States… than has been asked… since the Second World War.” It defines security interests broadly, articulating a commitment to defend only military concerns, but also more abstract values like “self-determination,” “political independence,” and “universal human rights.” Advancing democratic values abroad fits well within the framework of post-Cold War US foreign policy, but politicians from both parties have recently suggested more restraint in light of decades of conflict in the Middle East and failed nation-building campaigns.

That the United States continues to see itself as the “pivotal nation” in the Indo-Pacific is, therefore, incredibly important. Rather than adopting a more limited definition of American security goals, US officials have doubled down on an aspirational vision for US leadership in the region. Speaking in Jakarta in 2021, Secretary of State Antony Blinken quoted President John F. Kennedy when declaring President Biden’s goal for “a peaceful world, a community of free and independent states, free to choose their own future and their own system, so long as it does not threaten the freedom of others.” Implicit in that statement was the understanding that the United States would be deeply involved in ensuring that outcome in the Indo-Pacific in the years ahead.

Domestically, the articulation of US goals in the Indo-Pacific has been much different. For example, during his most recent State of the Union speech, Biden focused primarily on his efforts to reshore manufacturing from China, articulating a sense of victimhood about the “people that have been forgotten,” “left behind,” and “treated like they’re invisible.” The president’s message was clear: globalization has hurt people, China is to blame, and economic investment is headed home. Biden could have used the State of the Union to speak to the American people about the security challenges in the Indo-Pacific or announce a plan for how the United States would work with our allies to out-compete China. Instead, he announced that the United States would once again make drywall in America. He may have calculated that this type of message would be politically beneficial, but his choice creates a serious problem: while the Administration professes their support for a free and open Indo-Pacific abroad, their rhetoric at home suggests a much more protectionist and isolated worldview.

Moreover, while legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS and Sciences Act will address long overdue gaps in the defense industrial base, the extensive manufacturing subsidies contained in these bills have angered allies. Countries such as South Korea and France see the legislation as unnecessarily undermining them as key national security partners. Biden has admirable intentions in focusing his foreign policy on rebuilding the middle class, but often his protectionist policies are indistinguishable from former-President Trump’s isolationist vision of “America First.”

Faced with the growing threat from China, our allies will likely accept America’s protectionist economic policies due to the unmatched security guarantee the US military can provide. Similarly, the United States is unlikely to substantially decrease its presence in the Indo-Pacific anytime soon, regardless of domestic political pressures to prioritize investments that directly impact Americans. Thus, some may argue that the division between the free and open Indo-Pacific ideal and a more protectionist, inward-looking foreign policy is ultimately inconsequential. However, these competing narratives give rise to two critical problems.

First, they increase the risk of misperception on the part of Beijing. The domestic political environment within the United States may cause Xi Jinping to assume that it is less committed to upholding a free and open Indo-Pacific than the State Department or Department of Defense might suggest. If the United States is, in fact, willing to expend significant resources to uphold the rule of law and defend its allies in the region, then this misperception unnecessarily increases the risk of confrontation.

Second, much of the United States’ success in competing with China depends on the buy-in of and support from its allies and partners. Mixed messages may make these countries question US motives and commitment–unnecessarily weakening the United States’ influence in the Indo-Pacific region, and undermining policies like technology transfer bans that rely on the cooperation of allies such as Japan and the Netherlands.

To minimize these risks, Biden must make the case to the American people and the world that the goal of a free and open Indo-Pacific and a foreign policy for the middle class are not mutually exclusive. For example, he should draw a greater distinction between trading with China—a country that notoriously steals US intellectual property and uses forced labor in Xinjiang and Tibet—and trading with countries that share our values, respect the rule of law, and adhere to rigorous human rights standards. By taking a firm stance against unfair trade practices, Biden can help US companies compete fairly in the world economy, delivering economic benefits for working-class Americans without unnecessarily undercutting our allies.

The Biden administration should also embrace concepts such as “friendshoring” where the United States extends favorable trade conditions to our closest allies, taking advantage of each country’s strengths while protecting US national security. These policies can even benefit US workers. For example, the Heritage Foundation found that a free trade agreement with Taiwan could benefit both countries, generating significant growth in US exports in the beef, pork, and automotive industries. This type of agreement would be a win-win for the United States by demonstrating its commitment to its Indo-Pacific partners while delivering real economic benefits for American workers.

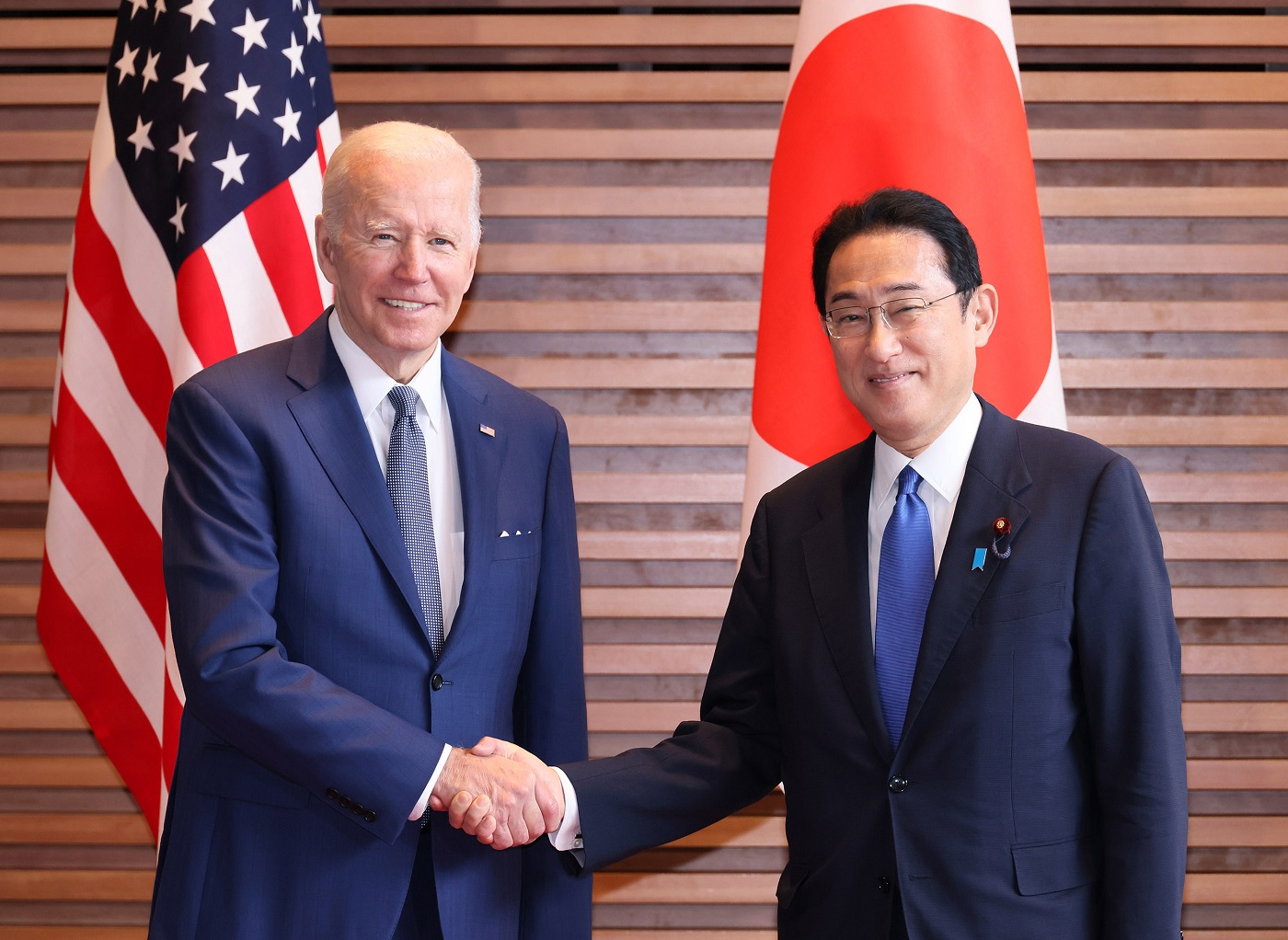

In the past year, the United States has made significant progress shoring up alliances in the Indo-Pacific from a security standpoint. During a recent White House visit, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida underscored Japan’s decision to increase defense spending to 2% of gross domestic product. Similarly, the United States and the Philippines reached an agreement to increase US access to military bases in the country. Without a cohesive economic policy to engage these allies, however, the United States risks undermining its progress and sabotaging the long term goal of developing independent supply chains.

While the idea of reshoring manufacturing and taking on the challenge of China alone may sound appealing in some political contexts, the United States cannot realistically face this challenge alone. It’s time political leaders in Washington embrace this reality. Rather than continuing to shift between the idealistic aspirations of a free and open Indo-Pacific and the more politically popular concept of a foreign policy for the middle class, the United States should make the case that these ideas are not mutually exclusive. In fact, only by pursuing them together can the United States create the type of cohesive foreign policy needed to meet the challenge posed by China.