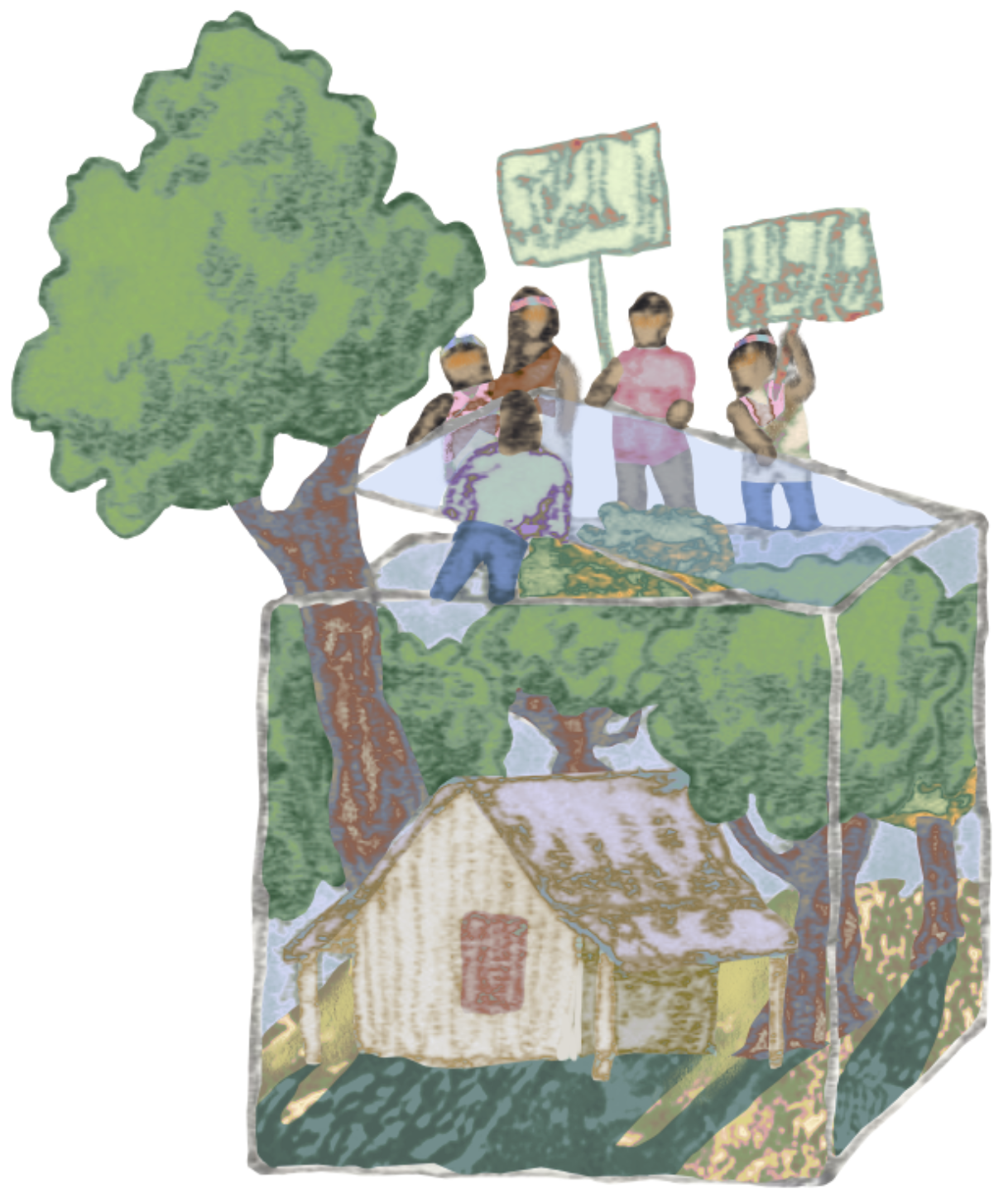

Brazil’s Cerrado region, the most biodiverse savannah in the world, is home to the geraizeiros, a native population of mixed Afro-Indigenous and European descent. Since their arrival in western Bahia over 200 years ago, the geraizeiros have lived in small villages in the savannah lowlands (baixões) and the plateaus (chapadas), cultivating the land with care and respect.

However, because many geraizeiros lack official deeds to the lands they live and work on, companies have recently been able to expand into the region and kick them off of the land they have occupied for decades. These companies laid claim to vast swaths of uncultivated land in the Cerrado before converting the native vegetation to soy, corn, and cotton monocultures. The Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America alone has acquired at least 800,000 acres of farmland in Brazil, primarily in the Cerrado region. These aggressive business practices have severely impacted the geraizeiros, leaving most of them displaced and disconnected from their ancestral lands.

In recent years, many countries in South America have been digitizing their land registries and establishing online databases that serve as birth certificates for rural properties. While land registries are not inherently harmful, mega-agribusiness corporations such as Cargill and Archer-Daniels-Midland use these registries as well as georeferencing technologies to deceitfully obtain property deeds that deprive Indigenous communities of their ancestral lands. But by working with non-governmental organizations and increasing oversight, South American governments can curb this continued land theft.

Although digital registries are relatively new, the ethos underlying their exploitative use is not. During the colonial period, debates over land registration and ownership in South America were often at the forefront of violent conflicts between European colonizers and the Indigenous groups they displaced. Since then, land-grabbers have capitalized on the general lack of centralized land registration systems and regulatory policies to claim ownership of community-owned lands without legal deeds.

In 2020, GRAIN, a small international non-profit organization supporting small farmers and community-controlled food systems, launched an investigation into how these new digital systems function. In its report, GRAIN argues that in several areas of rapid agribusiness expansion in South America, the digital system is “validating the historic process of land grabs.” Rather than recognizing the long-standing land claims of traditional communities, the report alleges, the system is expelling native communities from ancestral lands that they have occupied for decades or even centuries. Affected communities live in regions including the Llanos Orientales of Colombia, four states in the Brazilian Cerrado ecoregion, and three areas along the Paraná River.

Within each of these regions, landowners are required to register their land in what is formally known as a georeferenced cadastre—a supposedly exhaustive record of a given country’s property—if they wish to acquire the legal land deed, bank credits, and loans. Since the World Bank partially funds the cadastre process in many South American countries, georeferencing tools allow the international financial sector to play a decisive and expanding role in converting community-held rainforests and savannahs into agribusiness land. In Brazil, for example, the World Bank shelled out $45.5 million for the digital registration of private rural properties in the country’s rural environmental cadastre, allowing it to generate income from investments in agroforestry systems.

Unsurprisingly, this outsourcing of power and authority has had dire consequences for many indigenous communities. The cadastre system inherently caters to the needs of large companies and private actors who want to register individually owned allotments of land. The bureaucracy of cadastral documentation, coupled with the rigidity of the cadastral system’s definition of land ownership, makes it difficult for some native communities—who collectively occupy their land—to register their plots. Cadastres’ early iterations fail to record land occupation by these communities, making them “illegal trespassers” on the property they work and live on. The new landowners can then use the official cadastre and georeferencing records to go to court and evict traditional communal owners. Condoned by the rampant corruption in rural municipalities and courts, this sequence is disturbingly common.

Although much of this problem stems from misuse of georeferencing technology, the issue calls for a political solution. Local and national governments must put agrarian reform and collective land ownership issues on their political agendas. Governmental land use groups and agencies—the South American equivalents to the United States Bureau of Land Management—should allocate public lands to rural peoples in order to guarantee their collective territorial rights. Digital georeferencing techniques for land demarcation can and must be backed up by traditional ground truthing surveys. And rather than taking prospective landowners’ claims at face value, governments must independently verify them via a centralized land registration system organized to resolve conflicts.

Even if the government does not act, there are still a number of ways to guarantee land rights for Indigenous communities and other rural peoples. In 2019, the International Land Coalition (ILC) published “ILC Toolkit #9: Effective Actions Against Land Grabbing,” describing several strategies that landowners and activists alike can use to combat the global land-grabbing phenomenon. One of the primary ways the ILC encourages local groups to resist land-grabbing is through the development of community land registries, which allow landowners to register their customary land rights into a government cadastre and obtain formal land titles or certificates. This process helps integrate many indigenous peoples’ customary rights into the legal system and establishes proper land rights that help communities protect their lands.

The Higaonon, an indigenous tribe in the Mindanao region of the Philippines, has successfully implemented this practice and holds much of its land under customary tenure systems. Still, the lack of clear boundaries between neighboring groups has led to many disputes. In response, the Higaonon applied for a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT), a formal land ownership title. However, despite their efforts, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples has only formally registered 50 CADTs, limiting their effectiveness in protecting indigenous land.

Traditional knowledge and production systems—existing sustainably on communally held land—protect natural resources and are vital for human survival. But the longevity and viability of these systems are being put at risk by the “digital land grab.” We must do everything in our power to stop it.

[Editor’s Note: This article was published in the Fall 2022 issue of the BPR magazine.]