“Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.” With these provocative words, John Perry Barlow made his 1996 “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.” He presented a utopian vision of the internet—one defined by openness, freedom from government control, and a rejection of traditional sovereignty.

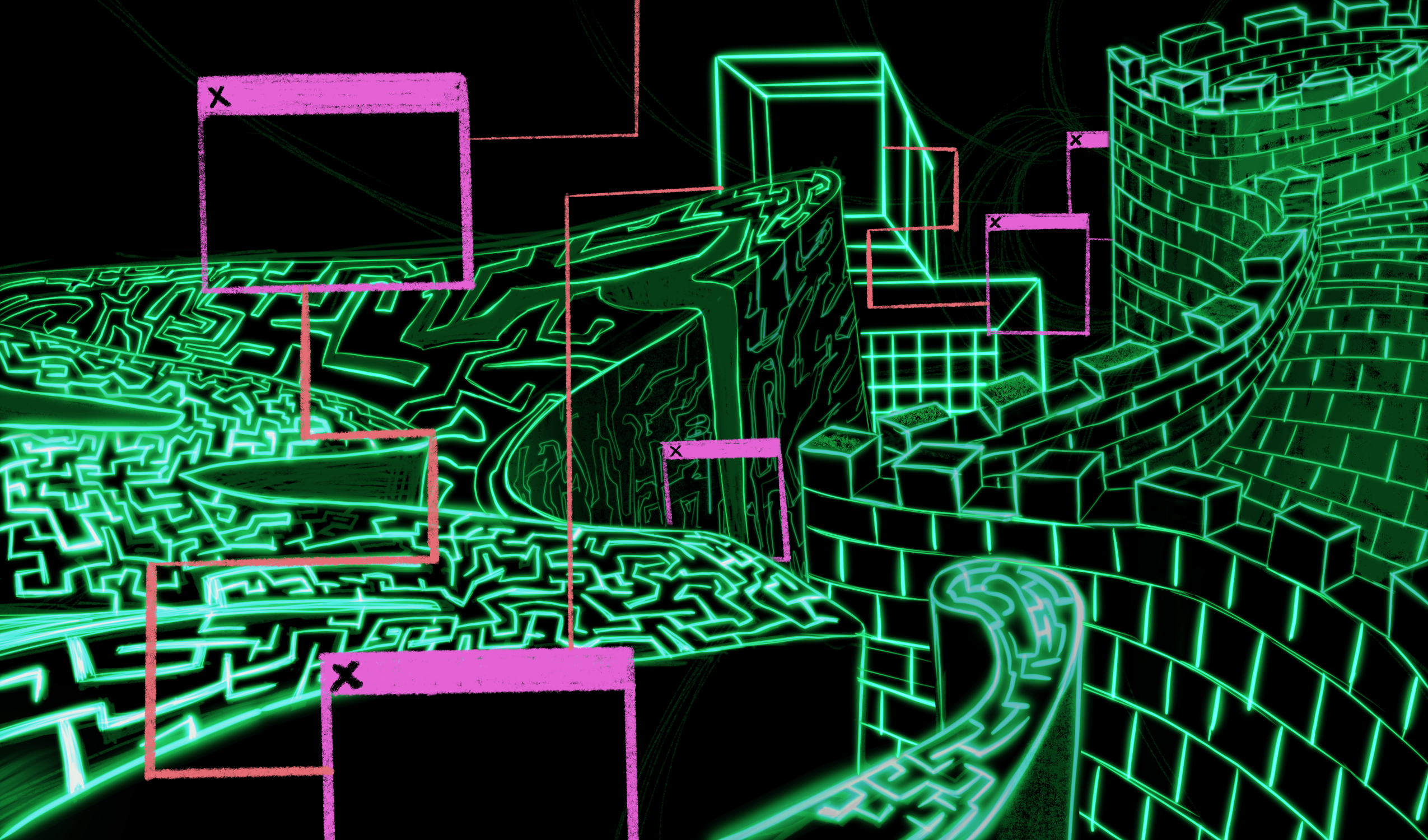

Yet, as political scientist Malcolm Anderson observes, “images of frontiers and the conceptions of territorial organization have been part of all major political projects” and form part of “what it is to be human.” Barlow hoped that the internet would escape the tendency to construct borders—cyberspace, he told governments, “does not lie within your borders.” Today, his cyber-utopian vision appears increasingly improbable as states erect cyber borders in the name of “digital sovereignty.” China has created the Great Firewall (防火长城), controlling all digital information within its borders. Russia’s RuNet, created in 2019, emphasizes “cyber sovereignty” by creating a domestic Domain Name System and removing Western software and hardware. In 2021, former German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other European leaders asserted that “now is the time for Europe to be digitally sovereign” by increasing EU internet regulations. Even the United States has considered erecting new barriers in cyberspace, including the recent effort to ban TikTok.

This digital sovereignty movement parallels the hardening of territorial borders during the 17th century. In 1648, the Treaties of Münster and Osnabrück, known collectively as the Peace of Westphalia, ended the Thirty Years’ War, establishing nation-states as the primary form of social organization and “creating conditions supporting the gradual hardening of borders between and among states.” Today, the world faces a similar moment in cyberspace. Chris Demchak and Peter Dombrowski, professors at the Naval War College, have declared the rise of a new “cybered Westphalian age.” As they argue, “No frontier lasts forever, and no freely occupied global commons extends endlessly where human societies are involved. Sooner or later, good fences are erected to make good neighbors, and so it must be with cyberspace.” Similar to the period after the Thirty Years’ War, states today are erecting fences in cyberspace to control and defend it, territorializing the internet.

The desire to create borders in cyberspace is understandable—cyberattacks, cybercrime, and disinformation operations pose a real national security threat. If left unchecked, they risk harming citizens and causing monetary damage. But leaders should be wary of embracing the Westphalian concept of cyber sovereignty. Democratic societies must consider whether abandoning a free, decentralized, and global internet serves their interests. A global internet provides unparalleled opportunities for innovation, economic growth, and free expression. Caving to a limited, territorial, and military version would jeopardize these noble objectives.

Despite its utopian aspirations, the internet has been intertwined with military objectives since its invention. The first version of the internet was ARPANET, a network designed by what is now the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in the United States. The project emerged amid Cold War tensions in the 1960s, with military leaders expressing a need to maintain reliable communications during a potential conflict. In 1983, military applications were transferred to MILNET, and in 1989, ARPANET became the Internet. However, military connotations have persisted in discussions of the internet. The emergence of cybernetics, the study of control in mechanical and biological systems, included what Harvard historian Peter Galison terms an “ontology of the enemy” that spoke to a new “age of information and control.” “War,” Galison argues, “gave the new cybernetic technologies a role to play in the Manichean drama of the world.” From its founding, the internet has always contained the capacity for destruction.

Despite its military origin, the Internet most notably enabled civilian forms of communication. With the first email message sent in 1972, ARPANET began to shift to the “World Wide Web,” a process that saw the “enormous growth of all kinds of ‘people-to-people’ traffic.” This network was highly decentralized. In contrast to ARPANET, the internet “was not simply bigger but also more flexible and decentralized.” The Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP), for example, specified that “there would be no global control at the operations level.” Instead, networked routers and devices could communicate with each other freely, facilitating economic and social interactions. In her book Inventing the Internet, Janet Abbate notes that decentralization was practical because it “minimized the need for ARPA to exercise central control over [the internet’s] expansion.” With the exception of basic network protocols like TCP, the internet became a largely open frontier where people could easily connect themselves to what became a global network of devices.

The globalized, borderless internet, however, faced the fundamental reality that the system was not secure. Countries at the center of the network—like the United States—that control key intercontinental fiber optic cables, data centers, and internet exchange points could exert what Henry Farrell terms “panopticon and chokepoint effects” to spy, restrict access, or attack users outside of the United States. Even as liberals argued that digital ties, like economic ones, would create shared interests and decrease conflict, it quickly became clear that actors at key nodes could leverage “weaponized interdependence” to harm adversaries. The Snowden leaks about National Security Agency (NSA) surveillance and the Obama administration’s decision to deploy the Stuxnet computer virus to delay the Iranian nuclear program demonstrated these fears. Centralization provided the United States with opportunities but irked other countries. For them, remaining connected through the US-centered global internet became a risk.

A borderless internet also posed risks for countries at the center of the global network, particularly the United States. In May 2021, a ransomware attack disrupted the Colonial Pipeline. More recently, the US government revealed that a Chinese state-sponsored cyber group was targeting US critical infrastructure in an operation termed “Volt Typhoon.” China has also compromised US telecommunications systems in an attack known as “Salt Typhoon.” From election interference threats by Iran to North Korean crypto hacking and individual ransomware attacks on everyday citizens and hospitals, cyberattacks have become increasingly prevalent. In the name of (cyber)security, even the country at the center of the open internet now sees cyberspace as something to be defended rather than shared for mutual benefit.

Finally, internet regulations have become increasingly ideological, incentivizing states to fence off their sovereign slice of cyberspace to enforce their value systems. An EU working paper, for example, calls for increasing Europe’s “strategic autonomy” to promote “European values and principles in areas such as data protection, cybersecurity and ethically designed artificial intelligence.” Despite close economic and security cooperation with the United States, Europe sees its values as distinct, requiring new forms of sovereignty in cyberspace to ensure data privacy and human rights. In other cases, the EU and the United States have collaborated to criticize China’s “social credit” system, reinforcing the brewing conflicts between countries over how to govern cyberspace.

The rise of Westphalian sovereignty in the digital realm is largely inevitable; however, leaders should resist the tendency to erect barriers beyond basic protections for securing elections, preventing critical infrastructure attacks, and combating transnational repression of dissidents. While states may fear that the internet can serve as a conduit for spying or cyberattacks, a global, open internet is also a tremendous opportunity, particularly for democratic societies. Enabling global free expression and the exchange of ideas ought to be seen as a valuable public good that can both weaken autocrats and bolster international collaboration.

In 2000, President Bill Clinton suggested that controlling the internet was impossible. He noted, “In the new century, liberty will spread by cell phone and cable modem. In the past year, the number of internet addresses in China has more than quadrupled, from 2 million to 9 million. This year the number is expected to grow to over 20 million.” While he acknowledged that China was trying to “crack down on the internet,” he was skeptical that they would succeed, saying, “Good luck! That’s sort of like trying to nail jello to the wall.” Two decades later, authoritarian regimes around the world have built digital walls around their countries to prevent unwanted ideas from spreading. Perhaps most concerningly, the United States has seemingly moved in a similar direction, deepening the “digital divide” by attempting to ban TikTok. While swaying the Chinese Communist Party is impractical, the United States and Western democracies should continue to advocate for a free and open internet.

From an economic standpoint, a global internet allows companies throughout the world to profit and bring innovative ideas to market. When the EU harshly regulates US companies—in some cases virtually pushing them out of the market or imposing significant compliance costs—this economic potential is decreased, and citizens are forced to live with less innovative products. In response to fines on Meta and Apple, the Trump administration released a statement making clear that “extraterritorial regulations that specifically target and undermine American companies, stifle innovation, and enable censorship will be recognized as barriers to trade and a direct threat to free civil society.” While every country has the ability to set their own laws, by advancing an expansive definition of sovereignty in cyberspace, the EU is just one example of how excessive internet regulation can stifle innovation and lead to more fragmented tech ecosystems.

While some element of security must be present in cyberspace, creating security measures does not mean rewriting the entire internet into a geographically divided and adversarial space modeled on the post-Westphalian state system. Perhaps one of the biggest ironies is that even as states push toward this bordered vision, they continue to advocate for extraterritoriality. The UK, for example, attempted to mandate that Apple hand over users’ encrypted cloud data stored at global data centers. Rather than comply, Apple removed the feature from the country. The proposed policy, while made in the name of security, represents both a clear affront to liberty and a bizarre concept of sovereignty, whereby Britain can force an American company to hand over private user data stored in data centers outside the UK’s borders. Thus, even as states erect borders in cyberspace, they continue to advocate for the right to infringe on other states’ supposed slice of the sovereign internet. A decentralized, open, and norm-based internet architecture would better solve this dilemma.

Barlow warned that in “China, Germany, France, Russia, Singapore, Italy and the United States, [governments] are trying to ward off the virus of liberty by erecting guard posts at the frontier of Cyberspace.” The chaos and danger of the past decades have shown that some guard posts are necessary to ensure election security, guard critical infrastructure, and protect citizens’ bank accounts and identities. But the march toward security has created a shift toward territoriality whereby cyberspace has become less free, less open, less interconnected, and more commodified as a political tool for ideological signaling. The drawing of borders and the militarization of cyberspace is becoming a threat to liberty. Democratic countries must think twice about which vision they hope to champion.