We have had many discussions on BPR about the affects of gerrymandering on American policy. To sum up: very few members of Congress are in danger of losing their seat to the other party. Instead, they need to protect their far flank from a primary challenge. This gives them little reason to move to the center and compromise. This has profound effects on American policy and the ability of elected officials to chase that elusive vapor of bipartisanship.

What is also happening, though, is the sorting of America’s populace into more homogenous areas. America’s demographers and scholars have been looking at this carefully.

This compartmentalization occurs because of residential choice and the deep divides in the demographics of different residential areas. In Coming Apart, sociologist Charles Murray designates certain postal codes “SuperZips” because of how high-income and high-education the areas have become. High-income, high-education people have clustered. Other zip codes have fallen behind the SuperZips. The SuperZips are clustered around major metro areas: San Francisco, Boston, Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, DC. Murray describes two neighborhoods: Belmont and Fishtown. Belmont represents areas like McLean, VA or Westchester County, NY – affluent and highly educated. Fishtown folks live more hardscrabble lives in post-industrial places like Pittsburgh or Pawtucket. An incredible portion of America’s college graduates and wealth end up in the SuperZips.

I wrote in a previous post about hub cities and how highly educated people cluster in these areas due to job prospects. The gap keeps growing. The New York Times’ Gail Collins and many others pointed out the city-rural gap in the 2012 election.

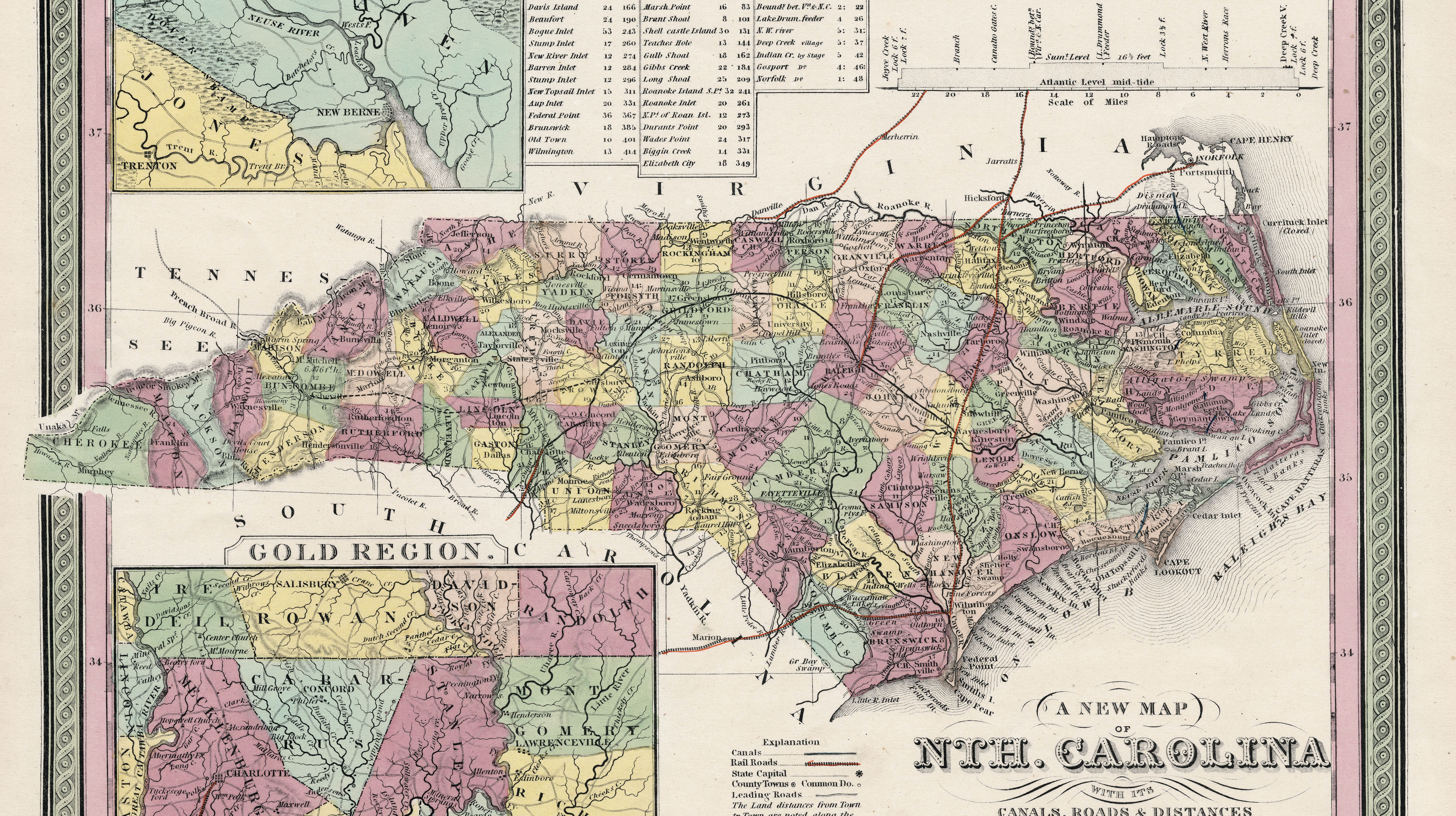

North Carolina’s recent vote on Amendment One (to make a constitutional amendment in the North Carolina constitution to ban same-sex marriage) provides an interesting case study. The Amendment One vote was a completely divided on city-rural lines. A look at this map shows these divides. Urban areas and especially college towns voted against Amendment One. Rural areas voted for. The weight of all the rural votes won out and Amendment One became law.

Sorting makes for strange politics. Just like gerrymandering, it gives representatives little incentive to compromise. If the Representative reflects their district well they do not rock that boat with bold moves. Many observers, including the Washington Post’s Ezra Klein, pointed out that Democrats won the national House vote, meaning that more people in aggregate voted for Democrats for House, but the House stayed in Republican hands because the geography of the vote was diffuse.

This becomes more personal for us Brunonians. Most Brown students will not settle permanently in Providence. When we graduate from Brown, we will want to move to places where there are lots of other young professionals for a social scene. Young people want a young neighborhood where they can afford to live. See, for example, Brooklyn, where young people with entry-level incomes move when they relocate to New York City.

Economics is the summing up of many individual decisions. So is politics. This sorting phenomenon affects both, in profound ways.