In the midst of a monumental trial fixed in the public eye, Bradley Manning’s recent transition to Chelsea Manning blew through the US media with exactly the amount of grace and sensitivity towards a disenfranchised minority that one might expect.

From the overtly ignorant and bigoted responses, like transgendered people being labeled a nonexistant (yet somehow still unnatural) “legend,” to the subtler misunderstanding of transgender identity when many media sources consistently misgendered her during the initial media coverage of her announcement, to a frankly ugly Twitter debate over how mentally ill she must be, Manning’s trial placed the issue of transgender rights in a national spotlight that has strenuously avoided the issue until now. And given the often negative responses to such an illumination, it seems that some serious national conversation is in order about identity is constructed along social as well as biological axes.

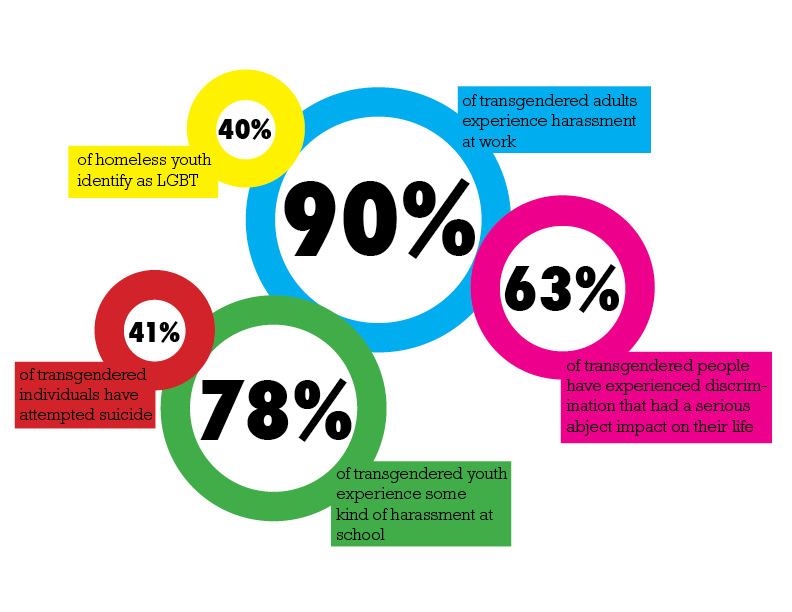

Transgendered people – individuals who identify as having a nonalignment of conventional gender identity and physical sex – face constant discrimination at home, in the workplace, in academia, and on the street. The National Transgender Discrimination Survey reveals sobering statistics about transgendered individuals, including a higher rate of suicide, extreme poverty, double the rate of unemployment as cisgendered people, higher rates of homelessness, discrimination in public settings, limited access to receiving updated ID documents, abuse by police and in prison, and denial of medical care at extremely high rates – overall, 63% of transgendered individuals have experienced discrimination that had a serious abject impact on their life because on their gender identity. For transgendered people of color, the numbers ratchet even higher as structural racism and transphobia intersect.

Despite this transphobia rampant at almost every institutional and social level (up to 40% of homeless youth identify as LGBT, largely because of rejection or abuse from families, while 78% of transgendered youth report harassment at school and 90% of transgendered adults report harassment at work) level, Manning’s situation has brought an amount of attention to two systems not big on transgender rights: the military and the prison-industrial complex. While transphobia – the discrimination, stigmatization or oppression of anyone who does not fit within the conventional gender binary – is rampant in US institutions today (it was only declassified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, from “gender identity disorder,” making a set of identities into a pathology, to “gender dysphoria” in 2013), blatant abuse of individual rights to freedom of identity expression are at play here. The repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell did not include transgender individuals under its umbrella, and being transgender is currently classified as an “unallowable medical condition,” the consequences of identifying as such are immediate discharge. While civil courts have often ruled that not providing resources for transgender individuals to transition in prison – like hormone therapy and sex-reassignment therapy – constitutes cruel and unusual punishment, the military does not follow the same line of thinking (despite research showing that transgendered individuals are twice as likely to join the military).

Manning, who has requested hormone therapy and sex reassignment surgery while serving her sentence, is not the only convicted prisoner to do so – earlier in 2013, a lawsuit was reinstated by a transgender inmate against a prison in Virginia, which had refused to grant her sex reassignment surgery, while in 2012 Massachusetts was ordered by a federal judge to pay for a sex reassignment surgery for an inmate. Despite these successes, transgendered individuals face extreme danger when in the prison system – one-fifth report harassment by police (higher for trans individuals of color), while 16% of those who have been to jail report physical assault and 15% report sexual assault. Hormone treatment is often denied, even if prescribed before prison, and individuals are often placed with inmates of their biological sex, prompting further abuse. Visibility has recently been raised about this issue with Netflix’s hit show Orange is the New Black featuring a prominent black transgender woman – even better, played by transgender actress Laverne Cox – as one of the inmates. Cox’s character must deal with having her estrogen supplements scaled back arbitrarily by prison staff and discrimination from prison officers and sometimes other inmates. Reflecting these issues – perhaps unsurprisingly given the Army’s recalcitrance in allowing gay rights – Manning’s request for medical intervention was denied.

Manning, who has requested hormone therapy and sex reassignment surgery while serving her sentence, is not the only convicted prisoner to do so – earlier in 2013, a lawsuit was reinstated by a transgender inmate against a prison in Virginia, which had refused to grant her sex reassignment surgery, while in 2012 Massachusetts was ordered by a federal judge to pay for a sex reassignment surgery for an inmate. Despite these successes, transgendered individuals face extreme danger when in the prison system – one-fifth report harassment by police (higher for trans individuals of color), while 16% of those who have been to jail report physical assault and 15% report sexual assault. Hormone treatment is often denied, even if prescribed before prison, and individuals are often placed with inmates of their biological sex, prompting further abuse. Visibility has recently been raised about this issue with Netflix’s hit show Orange is the New Black featuring a prominent black transgender woman – even better, played by transgender actress Laverne Cox – as one of the inmates. Cox’s character must deal with having her estrogen supplements scaled back arbitrarily by prison staff and discrimination from prison officers and sometimes other inmates. Reflecting these issues – perhaps unsurprisingly given the Army’s recalcitrance in allowing gay rights – Manning’s request for medical intervention was denied.

The way that the Army and reacts to Manning’s transition will set a public precedent, good or bad, for the way that transgender individuals are treated by an institution ostensibly meant to protect the freedom of Americans – including in the realm of gender identity. Gender identification should not define someone’s worth, unless you want to argue that gender is indicative of an innate set of personality traits that make a person somehow “better” than others – an idea that we generally ascribe to abandoning with the Civil Rights Movement.

The issue of whether Manning is guilty or not is irrelevant here – she is still afforded the rights of an inmate under the US Constitution, and being denied appropriate medical care comprises a violation of those rights. Given the intense amount of prejudice and discrimination that transgender individuals face on a day-to-day basis, the struggle she faces to access appropriate care and acceptance for her transition will undoubtedly be long and difficult. But her unique position of being a transitioning transgendered person in the midst of such a public storm can serve as a starting point to mobilize support for a minority that suffers the very real effects of heterosexism embedded in our society.