California’s housing crisis is well-documented. Palo Alto, home to Stanford, offers subsidized housing assistance for any household with an annual income of less than $250,000. In the Bay Area, even doctors and lawyers are struggling to afford sky-high down payments and mortgages: the median house price in San Jose is one million dollars.

Part of the problem is that those who do own property in those areas have vehemently resisted efforts to build more housing units, which they worry will affect their home values and over-crowd public schools. Another part of the equation, though it is often overlooked, is California’s Property 13. This law freezes California property taxes at one percent of their valuation at the time of purchase or in 1978–whichever came later–and was publicized as the catalyst for a “taxpayer revolt” across the nation. Economist Richard Reeves wrote in the Seattle Times that Prop 13 was simply “a scheme by the people who got here first to preserve their lifestyle and life savings at the expense of newcomers.” This unfairness visibly plays out in the dramatically unequal property taxes levied on owners of similar properties: someone with the good fortune to have been able to purchase property in 1978 may end up paying less than 10 percent of their neighbor’s tax burden.

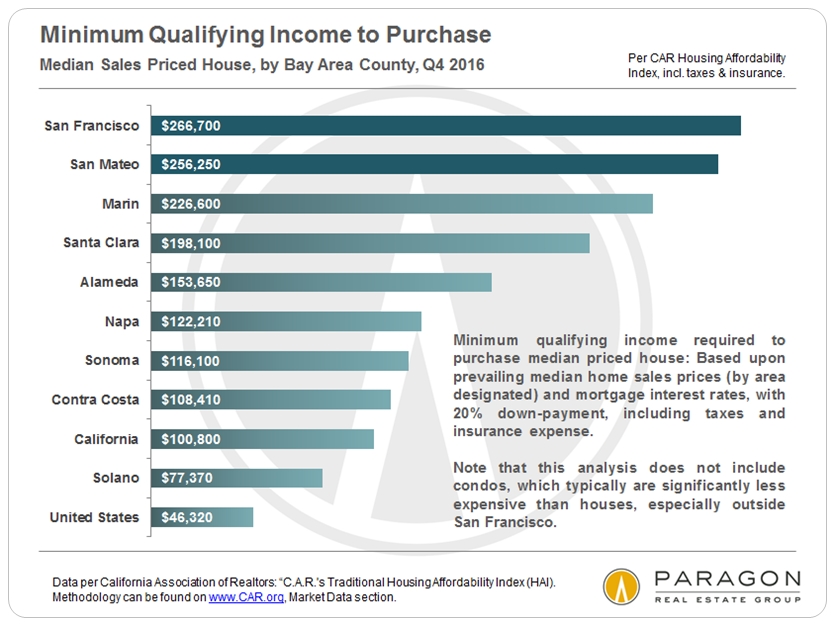

In this way, Prop 13 is a regressive tax benefit. Those who stand to benefit most from reduced property taxes are those who would otherwise have paid the most: Californians who own high-value properties, or properties that became high-value but were not at the time of purchase. Even worse, because Prop 13 caps the property tax revenue a local government will receive, many towns must resort to alternative sources of revenue. One popular strategy is to increase sales tax, which applies an equal burden to everyone regardless of their income. (In 1975, more than 95 percent of the typical city or county’s tax revenue was from property tax; today, that number is closer to 65 percent.) For a state frequently accused of being too liberal, it is surprising that California’s “third rail” is a law that disproportionately protects an overwhelmingly wealthier, older, and whiter group of Californians than the general populace. Even more interesting is the importance of the Bay Area specifically—while frequently thought to be the most liberal part of an already “too-liberal” state, its residents are most affected by this uncharacteristically conservative law. The dramatic appreciation of Bay Area property prices has produced both Prop 13’s biggest winners—including Palo Alto, with an effective property tax rate of 0.42 percent—and losers, an unhappy group of perpetual renters composed of Twitter engineers, doctors, and Facebook cafeteria workers alike.

Whether Prop 13 is even legal was brought into question by the 1992 Supreme Court case Nordlinger vs. Hanh. Nordlinger, a new homeowner, sued by claiming that Prop 13 violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause: it was unconstitutional, she said, that she had to pay so much more in property taxes than her neighbors did. In the end, Nordlinger lost the case—the Court declared that the state could reasonably tax new and older homeowners differently because older homeowners had a greater “interest” in their property. However, it is important to note that the Court conceded the constitutionality of Prop 13 with Justice Harry A. Blackman remarking in the majority opinion that the law appeared to “vest benefits in a broad, powerful, and entrenched segment of society.”

Prop 13 also contributes to a “lock-in” effect for longtime owners; with each passing year that their property appreciates in value, they stand to benefit more and more from Prop 13 and have increasingly more to lose by moving to another home, where they would be paying the “full” property tax. This effect is only compounded by the fact that under Prop 13, families are allowed to carry out intergenerational transfer of property without property value reassessment. The property turnover rate in California has shrunk from 16 percent in 1977, the year before the law was passed, to less than six percent in 2014; this turnover rate will only continue to decrease as California coastal property prices soar.

Research by Wasi and White for the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) demonstrates that from 1970 and 2000, “The average length of ownership rose by less than a year among homeowners receiving the lowest tax relief, compared to two to three years for those receiving the highest tax relief.” That is, average tenure length increased by less than one year in inland California cities, where property prices have increased gradually—but by more than two years in the Los Angeles area and by three years in the Bay Area, where prices have increased dramatically. (Recall that the greater the difference between a home’s 1978 and current valuation, the greater the impact of Prop 13.) This means that homeowners in places like Palo Alto are the ones who are least likely to sell. We can find further evidence of Prop 13’s “lock-in” effect by examining what happens when this burden is lifted. In 1986, a new amendment allowed homeowners aged 55 or older to maintain the tax benefit stipulated by Prop 13, provided they move into a similarly-priced home in the “same county or a county with a reciprocal relationship.” 55-year-old homeowners are now 20 percent more likely to sell their homes than 54-year-old homeowners, suggesting that many of those 55-year-olds specifically waited to sell in order to retain their current property taxes.

The effect of Prop 13, then, is essentially the same in action as rent control. Just as people who live in rent-controlled apartments are especially unwilling to move, longtime homeowners in California–especially those who live in desirable regions like the Bay Area, where demand for housing is high–are particularly unwilling to sell unless they plan to move out-of-state or are already retired.

Furthermore, Prop 13 ensures that becoming a new homeowner is extremely difficult; not only are homeowners unwilling to sell, but many renters are also unable to buy. This situation only exacerbates the inability of young people to purchase affordable property. A 2005 study showed that young Californians are significantly less likely than their same-age peers across the nation to own property–even when compared to young people in other famously expensive states such as New York. This discrepancy, however, is not present in 1970 census data–a telling signature of Prop 13.

Some argue that Prop 13 will drive businesses out of the state. After all, repeal of Prop 13 will force many businesses to pay much higher property taxes, as they would be based on a current, accurate assessment of their property’s value. Perhaps California needs Prop 13 to keep businesses in California, which was ranked the least business-friendly state in the nation and the second most expensive state to conduct business within.

However, California can offer other incentives to businesses to stay in state. For instance, a tech startup may not want to rent highly expensive offices in the Bay Area, but they may still need to in order to attract the top tech talent that is overwhelmingly located in the area. Actors have little choice but to live near Hollywood, and many businesses, such as apartment complexes or golf courses, have no choice but to remain in California. Furthermore, reform of Prop 13 may actually encourage the creation of new businesses and has support among small business owners, as the current policy heavily favors established businesses who are longtime owners of their property—under the current model, new businesses may be taxed at five times the rate of established businesses. Although specific incentives such as access to the Silicon Valley talent pool or proximity to Hollywood won’t affect the majority of businesses, Prop 13 reform would level the playing field by levying an equally effective property tax rate on neighboring businesses.

Realistically, it will be extremely difficult to pass Prop 13 reform. When the law was passed, it included a clause that will require a 2/3 majority to pass property tax reform; in a state where the majority of adults are homeowners, it will be difficult to persuade them to vote against their financial interest to rectify issues that don’t directly hurt them. It may be more politically feasible, for instance, to argue that children should not be able to inherit their parents’ property tax benefits under Prop 13, or to advocate for a more relaxed Prop 13 that allows a 3 percent annual appreciation of taxes, as opposed to the current 2 percent. Another possibility is to end Prop 13 for businesses only: for example, a split-roll tax reform might charge all businesses the same 1 percent property tax rate. But despite the difficulty of suggesting reform of such an entrenched policy, California should still aspire to live up to its progressive ideals and reform a regressive tax loophole that, while somewhat arbitrary, concentrates capital in the hands of those who had the good fortune to buy a house prior to 1978.