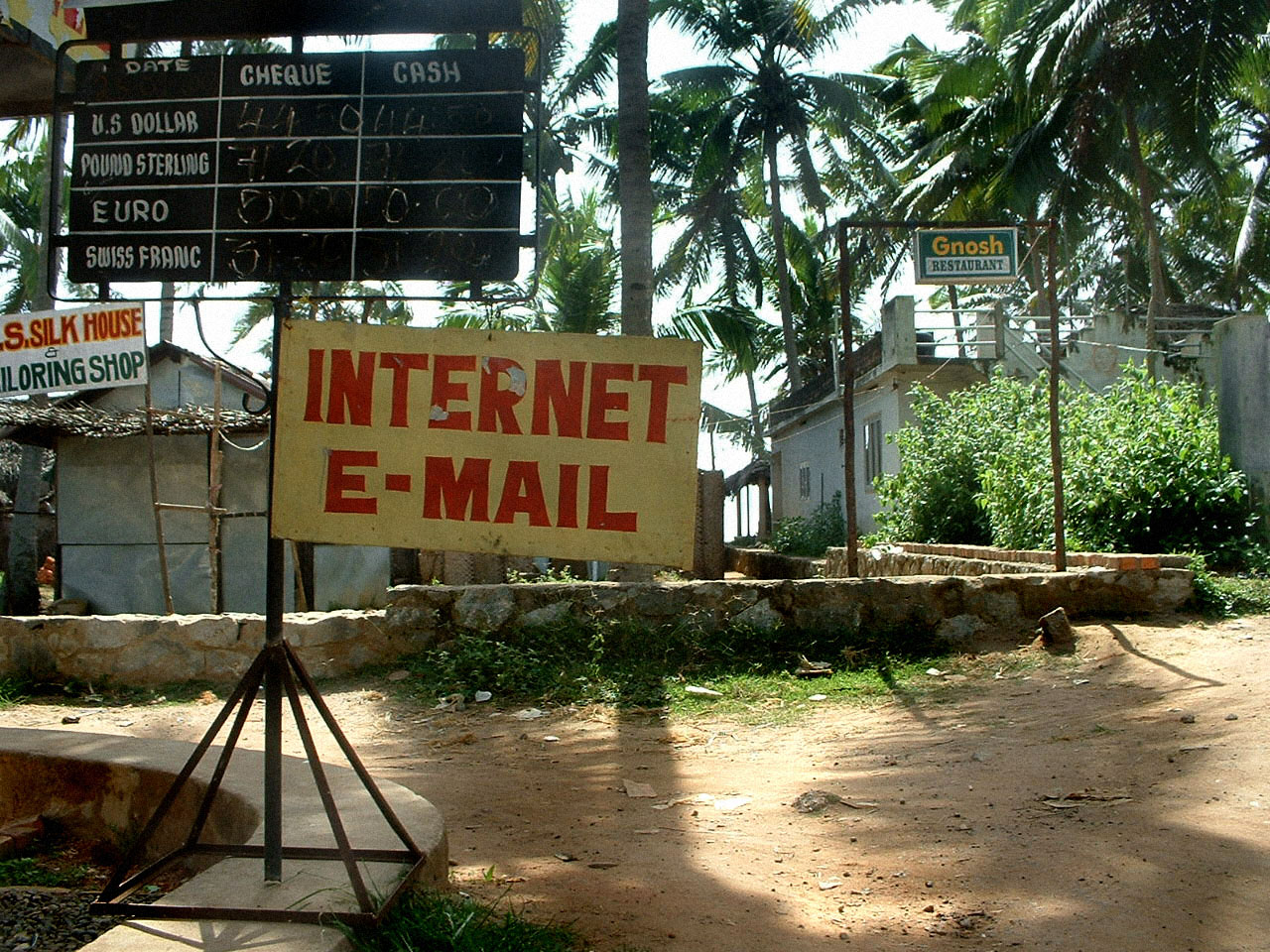

Upon its inception, Facebook instantly took America by storm — sweeping across college campuses, captivating the youth demographic, and, finally, establishing itself as an essential social media fixture among Internet users. Now, in an increasingly global age, one might assume that citizens of developing countries would be next in line, eager and ready to accept Facebook and all the latest, trendy technological accessories it has to offer. Yet, interestingly, this has not been the case in India. The country has been giving Facebook a hard time — and for good reason.

Last week, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) officially banned Facebook’s Free Basics, an app launched in 2013 as a part of its Internet.org initiative. Marketed as a tool promoting digital equality for individuals with no Internet, the application provides access to a limited selection of websites and platforms. Facebook’s logic is that some accessibility is better than none. However, members of the TRAI and the Indian telecom industry along with Internet activists soon identified Free Basics as a violation of net neutrality, a tenet of digital ethics that ensures equal access to all information on the Internet. In basic terms, net neutrality preserves consumer’s choice of reading material and thereby protects open forums for free speech, public opinion, and a balanced dissemination and exchange of ideas. Furthermore, net neutrality guarantees that budding start-ups, such as Facebook itself during its nascent stage, will be able to self promote online without fear of monopolization by other web competitors, ensuring an even playing field for small businesses. These benefits have led figures from Rajan Anandan, head of Google India, to Tim Berners-Lee, the so-called creator of the Internet, to openly promote net neutrality as an industry standard worldwide.

Yet amidst these recent criticisms, Marc Andreessen, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist and member of Facebook’s Board, added fuel to the fire by tweeting, “Anti-colonialism has been economically catastrophic for the Indian people for decades. Why Stop Now?” This inflammatory comment brought to the forefront the uncomfortable comparison of Facebook’s expansion to India’s colonial period, a concept evoking the image of the heroic Westerner swooping in to “save” or “help” the impoverished. Andreessen’s comment only intensified a long existing and reasonable sentiment in Indians to be suspicious of Western influence and advances.

But the idea that some is better than none is also highly flawed. The Free Basics program offers limited services to developing areas, implying in turn that these communities have simpler or different needs and standards than those in more developed societies. In response, Indian commentators have accused the program of creating “poor internet for poor people.” It seems myopic for Facebook to assume the app in its current state could be a be an end-all solution for the developing world and equally dangerous to attribute the potential for widespread social change to the narrow confines of the tech sector. Instead, Facebook could strive to further incorporate locals’ voiced needs in their efforts. In fact, according to many bloggers and commenters on Mark Zuckerberg’s own promotional Facebook posts, most people are asking for open web accessibility, a liberty most Westerners take for granted. As any other nonstate external actor working to benefit developing communities, it is important that Facebook contextualizes its work within the framework and historical narrative of the country it is entering.

Furthermore, Facebook seems misguided in its promoted image towards the developing world. In actuality, its current audience appears to be an Internet-literate one. The app is presented with an altruistic basis catering to the lowest of the pyramid, the “two-thirds of the world,” without connectivity. This intended audience is evident in examples such as the Free Basics site, which writes, “Imagine the difference an accurate weather report could make for a farmer planting crops,” and in Mark Zuckerberg’s own promotional anecdotes, like one about a farmer named Ganesh. However, consumer research has revealed that a large percentage of Free Basics users were already on the Internet as only 20 percent of users were not previously active. So if the majority of Free Basics users already have Internet access, the situation is not simply a stark divide between poor people with no connectivity and those who do, but rather current users who wanted general internet access or data bonuses. In turn, the original view of Facebook’s target Indian audience as a general “poor” demographic may be completely unfounded or at least require reexamination, calling into question the entire philanthropic basis of the project.

So, given this information, what are Facebook’s and India’s alternative options for Internet accessibility? Amidst all this talk about American apps, the Indian government’s own initiative to promote Internet access, Digital India, has been overshadowed. Although proposals such as the National Optic Fiber Network project have been less successful, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been pushing for improvements in digital development through acts like promoting domestic innovation. Just this past week, Modi announced a new platform to help farmers determine optimal pricing for their crops. Following a meeting this past fall with Silicon Valley tech companies, Modi also still remains interested in collaborating with firms to develop the nation’s digital infrastructure.

Accordingly, many private firms have stepped up to offer programs with completely open Internet access, such as Google and its recent India WiFi hotspot initiative. A notable Mozilla project in Bangladesh, which provides 20 GB of free data per day after individuals view an advertisement, is another similar program that guarantees open access as well. Such projects have received favorable reception among both consumers and free Internet advocates alike. If full Internet access programs are viable and preferred by locals, it seems only natural to pursue these opportunities instead.

But there is some hope for Facebook’s Internet.org, though. One feature separate from Free Basics, Express WiFi, works with local entrepreneurs to promote increased connectivity. Through a community-based approach in which individual sellers across villages sell data subscriptions to citizens, the program spreads full access Internet resources in a much more integrated manner. Initiatives such as these that entail collaboration from natives and that network local merchants seem like feasible alternatives.

Impactful initiatives by the tech private sector in the global market require not only a shift in practice, but also a shift in perception by integrating locals’ visions. Despite all the flak it’s been receiving, Facebook has demonstrated its potential to redirect its efforts meaningfully through programs like Express WiFi. By providing open internet services while empowering the individuals for whom the app was created, Facebook can create a win-win situation for all.