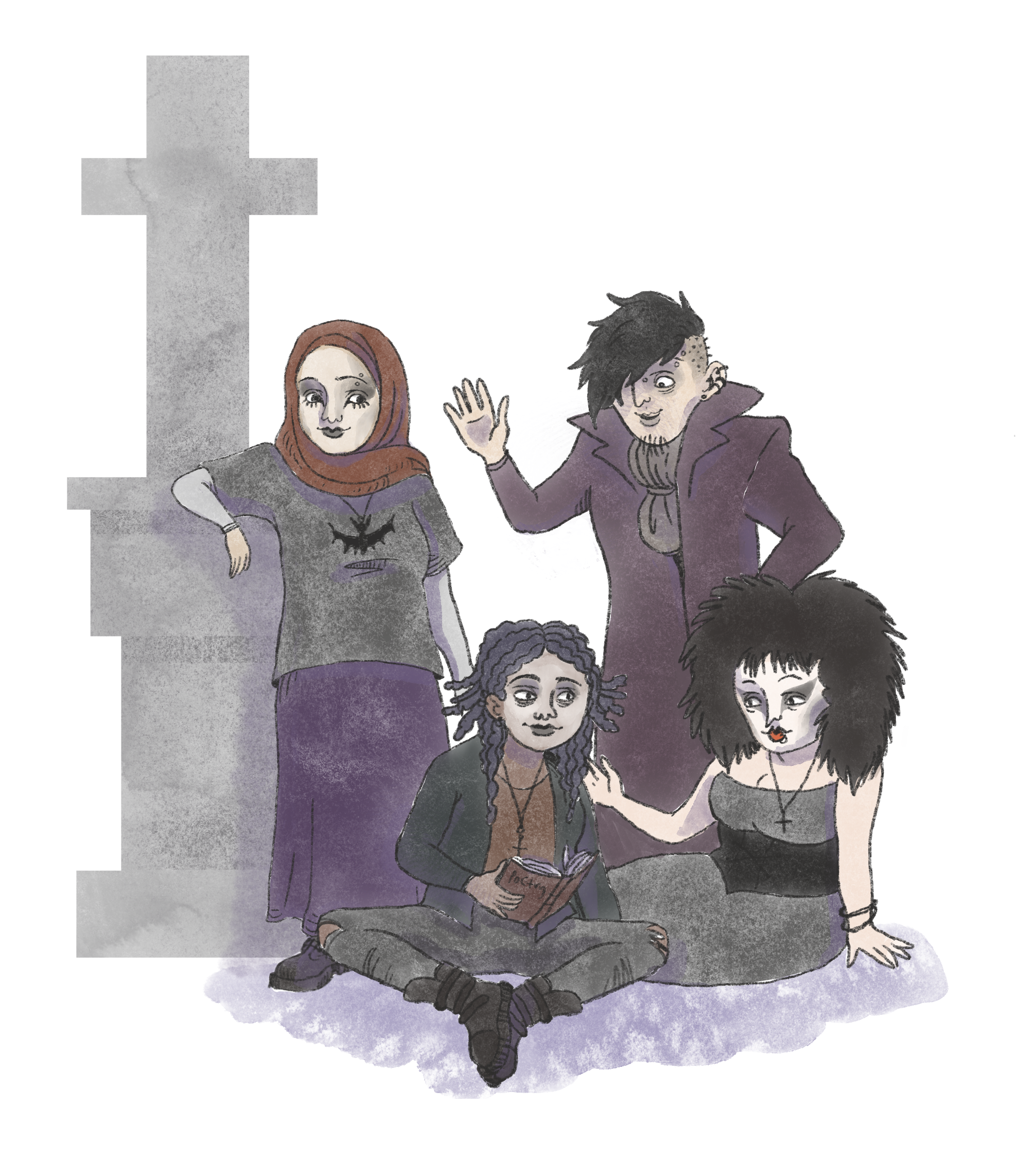

Marked by heavy layers of black clothing, comically tall boots, eccentric eyeliner, and coils of silver chains, goth subculture emerged in 1970s Britain as an offshoot of the punk movement. Since then, both subcultures have mainstreamed radical, anti-establishment views by disrupting music and fashion norms worldwide. Just as punk music typically communicates anti-authoritarian messaging, many classic goth and goth rock bands advocate for non-conformity or even outright rejection of the capitalist status quo. Despite the leftist views surrounding orthodox goth ideologies, the community has recently been suffering from a rise in racist and far-right views. In response, the goth community must center and be more inclusive of people of color within the community, thereby realizing the alignment of its founding principles with the goals of Black and Brown liberation.

What does it mean to be goth in the first place? While fashion and makeup are the main identifiers by which non-goths identify goths, the reality is that the political and philosophical principles of the gothic undergird fashion choices. The gothic aesthetic permeates all aspects of culture: music, film, art, architecture, fashion, politics, and more. More broadly interpreted across these disciplines, the gothic necessitates a resistance to the status quo, skepticism of blind optimism, and recognition of the dark side of human nature. Goths reclaim the things that are meant to terrify us and repurpose them as objects of beauty or admiration (hence the use of skulls, spikes, and chains in goth attire). In an homage to goth’s punk roots, the main traits that make an individual goth are simple: listening to goth music and adhering to the subculture’s foundational political principles. The anti-capitalist and anti-consumerist nature of the subculture, for instance, is so important that goths often follow in the “DIY” footsteps of their punk counterparts by creating their clothes from scratch or goth-ifying thrifted pieces in order to avoid superfluous consumption.

In contrast to the outwardly leftist ideologies projected by the majority of the subculture, certain sects of the goth community are unfortunately no strangers to far-right and white supremacist viewpoints. Colorism in particular has been an issue within the subculture, especially due to the frequent fetishization of striking paleness. Because being goth centers around the idea of embodying the “Other,” many goths reject commonly-held beauty standards and traditions. Rather than applying foundation and bronzer that match or accentuate one’s natural skin tone, goths often apply stark white bases and over-the-top eyeliner designs. This has led some to argue that only naturally pale-skinned people can be “true goths.” The assumption that being goth necessitates whiteness fails to recognize that darker-skinned members are already othered by white society. Despite this clear contradiction, the racist and colorist idea of gothness as only whiteness still permeates some aspects of the community. Gothic Beauty Magazine—one of the most prominent publications within the community—has yet to feature a Black model, and it rarely deviates from its convention of featuring blue- and green-eyed women. While the magazine has been successful in popularizing the subculture, it has also been complicit in deviating from the orthodox understanding of goth as a community that is both inclusive and anti-racist. These deviations have had real-world consequences: Some goth people of color have even reported that they experienced racially-motivated harassment at goth shows and performances.

Alongside the exclusionary practice of implicitly attaching whiteness to gothness, there has also been a recent trend of goths promoting more explicitly far-right views, especially online. With the recent rise in content by goth creators on social media platforms such as TikTok and Tumblr, goth fashion and music have become more popular in online spaces. While the online popularization of goth creative expression has successfully brought many new members into the subculture, it has also drawn some to blindly follow goth fashion and music trends without recognizing the political values that underpin them. On TikTok in particular, the short video format has been useful in showing off goth outfits and makeup inspiration, but less successful in presenting more extensive explanations about goths’ historic political affiliations and connections to the punk subculture. As a result, many inclusive principles and norms of the goth community have not translated well into online spaces. Since 2017, slogans such as #gothright, #gothsfortrump, and #gothnationalism have been on the rise on X. In a similar vein, goths with apolitical or even conservative viewpoints have become increasingly common on TikTok. These posts deprive goth of the life that was breathed into the subculture by the punk movement.

To remedy this issue, the goth community must recall its founding principles and recognize how they align with leftist ideals—specifically, Black and Brown liberation. Ironically enough, many goth symbols—such as the Ankh, skulls, and bones—are borrowed from Egyptian, African, and Native American cultures. The phenomenon of right-wing goths wearing these symbols while simultaneously marginalizing Black and Brown members of the subculture represents a broader disconnect between goth orthodoxy and recent cultural trends within the community.

Beyond borrowed symbols, people of color have another inherent connection to goth. Leila Taylor—a writer and designer whose work focuses on the relationship between history, horror, and the gothic—argues that a truly gothic perspective on the world attempts to cast light on the darkest fears and anxieties of society. For states built on the exploitation of Black and Brown bodies (such as the US), these anxieties are ever-present, but the gothic can take ownership of these fears and turn them into something useful. Taylor’s analysis is that many Black and Brown individuals, having contended with histories of genocide, colonialism, and exploitation, are required to construct their identities within an enforced acknowledgment of the darkest aspects of human society, thereby embodying the gothic (even with no makeup or boots on). In practice, even as they have felt cast off by the rest of their community, many goths of color have begun to form their own groups on Tumblr and Facebook to celebrate the intersections between gothness and marginalized identities. In opposition to the narrative that gothness is whiteness, several goth communities are vibrant and alive in countries such as Nigeria and Brazil. Because it focuses on horror and trauma, goth culture has the unique ability to acknowledge and confront histories of colonialism and slavery against Black and Brown individuals. Especially during a time in which education systems across the US are attempting to erase and rewrite histories of slavery, the narratives and experiences of Black and Brown goths can serve as a reminder of the atrocities of the past and the importance of discontinuing them in the present. Remembering and recognizing these horrors is a prerequisite to preventing them, and Black and Brown goths are uniquely positioned to do so. There is something especially goth, therefore, about being a person of color.

The challenge to the goth community is this: center Black and Brown voices beyond performative inclusion and call out the appropriation of goth ideologies that perpetuate injustice. The subculture has a large membership that spans multiple countries and ethnicities, so recognizing and welcoming differences in identity is imperative. Greater education efforts is one potential strategy that current orthodox goths can employ. While it is not necessary to turn the goth subculture into an eccentrically-dressed book club, increasing awareness of the tangible meaning behind goth is imperative. By popularizing and passing down the history of gothic art, music, and literature, orthodox goths can fight misconceptions and turn those with conservative values away from the subculture. It would also encourage newer or less informed goths to explore the rich history of goth. A dive into gothic literature, for example, shows the contributions of Black authors and the intersection between gothic literature and slave narratives. On a broader level, these connections reveal that goth has always crossed state and racial lines.

While these education efforts may sound abstract, a few social media creators are already taking them on. By creating videos that rebut prejudiced misconceptions within the community, these creators draw goth back to its original intentions. Similarly to the role of gothic literature, goth music often reinforces the anti-capitalist, anti-racist MO of the community, so videos that use, popularize, and analyze goth songs and lyrics are also particularly useful. Shining a light on artists of color within the music genre also helps to provide a greater platform to non-white contributors to the community.

It is also important to challenge those who attempt to pull goth culture away from these ideals. Similar to how the punk movement was able to successfully push neo-Nazis out of punk spaces, goths must fiercely respond to the encroaching alt-right presence within the community. Rejection of these ideologies is the only way to ensure that the subculture remains focused on the very principles that it was founded on and guarantee that Black and Brown goths feel a sense of recognition within the community as a whole. Goths must understand that, despite internal differences, the fundamental goth principles of anti-authoritarianism and anti-capitalism are areas of common ground that all goths must collaborate on to achieve collective liberation from systems of power that oppress all people, goth and non-goth alike.