Crime and punishment: ideas central to human society that have long been debated by philosophers, academics, and politicians. We might believe that decisions about who gets punished, and for what, are ones rooted in fact and fairness, but history has shown that what constitutes “crime” cannot be separated from politics. Nobody exemplifies this more than President Donald Trump, who, at the start of his second term, has made crime a centerpiece of political discourse by intertwining it with issues like immigration, abortion, and even the economy. While presidents in the past have taken strong measures to tackle crime, like the “War on Drugs” declared by Richard Nixon and waged by Ronald Reagan, Trump chooses a more rhetorically charged approach to the tough-on-crime mantra. His claim on the 2024 campaign trail that “one rough hour [of policing]—and I mean real rough” would “end [crime] immediately” underscores the severity and incendiary nature of his rhetoric.

Historical context can help explain how Trump became so emboldened. Long before he began saying the quiet part out loud with overtly bigoted messaging came a bipartisan effort to utilize demeaning, racially coded rhetoric as a means of incorporating crime into the political mainstream. While Trump certainly aggravates this movement, capitalizing on fears within the American electorate, he is in no way its originator.

The modern tough-on-crime narrative that Trump perpetuates began with Nixon, who introduced the term “law and order” during his 1968 presidential campaign. He linked crime to social unrest and liberal policies, using this connection to appeal to voters concerned with civil rights progress. Nixon’s Southern Strategy balanced support for federal desegregation with racially coded language framing crime as an urban, Black issue—all in an effort to appease southern voters. In office, he declared a “War on Drugs,” describing substance abuse as “public enemy number one” and expanding federal law enforcement. This strategy quickly became a political tool used to target Black activists and antiwar protesters.

Ronald Reagan escalated this approach, centering his first campaign around cracking down on drug use and crime. At the time, however, only 2 percent of Americans viewed this as a top priority, reflecting a tendency for politicians to stoke anxiety and fear surrounding crime rather than respond to existing concerns. In office, Reagan signed the controversial 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which imposed harsh mandatory minimum sentences that disproportionately impacted communities of color, primarily African Americans. America’s current problem with mass incarceration can largely be attributed to this legislation, with some scholars even describing Reagan’s presidency as the founding of a carceral state. But beyond discriminatory policymaking, his administration’s rhetoric—sensationalizing the “crack epidemic” and promoting figures like the “welfare queen”—reinforced racialized crime narratives by asserting that poverty and crime are endemic to certain groups of people. Nixon and Reagan transformed crime into a partisan weapon, associating it with racial minorities and creating a political environment where future leaders like Trump feel emboldened to lash out at immigrants, marginalized communities, and even political opponents. Trump’s rhetoric might be more overt, but his predecessors certainly helped pave the way.

While tough-on-crime rhetoric began primarily as a Republican tool, Democrats soon embraced it to avoid appearing “soft.” Former president George H.W. Bush helped catalyze this process with the infamous Willie Horton ad during the 1988 presidential campaign, which highlighted the story of a Black man released on furlough who then committed a violent crime, hurting the campaign of Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis. This Republican strategy of racialized weaponization cemented crime as a political weapon and pressured Democrats to adopt harsher stances. Former president Bill Clinton sensed the importance of presenting as “tough on crime” and responded by proving Democrats could be just as punitive as their Republican counterparts. His 1994 Crime Bill—the most sweeping crime legislation in US history—expanded policing, increased incarceration rates, and introduced “three strikes” laws that imposed harsher sentences on repeat offenders. Then first lady Hillary Clinton made her infamous remark describing teens of color as “superpredators” who were incapable of possessing empathy and thus more dangerous than their white counterparts. By the end of the 1990s, harsh rhetoric surrounding crime had become fully bipartisan, allowing future leaders like Trump to continue escalating this fear-driven approach with limited pushback from either party.

However, not all presidents embraced this ideology. Former President Barack Obama took a markedly different approach to crime, focusing on systemic policy reform rather than fear-driven rhetoric. His administration sought to quietly shift how politicians approach crime, taking measures to reduce mass incarceration, commuting sentences for nonviolent drug offenders, and promoting police reform efforts. Rather than using crime to stoke public fear, Obama framed it as a policy issue rooted in poverty and inequality. This approach sparked backlash, particularly from conservatives who portrayed Obama as weak on crime amid nationwide protests and the founding of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Right-wing media outlets amplified narratives of urban chaos and rising lawlessness, despite an overall decline in violent crime rates. The emergence of the Blue Lives Matter movement and calls for “law and order” in response to rising social justice movements signaled a return to Nixon-era rhetoric, setting the stage for further escalation. By the time Trump launched his 2016 campaign, polarization surrounding the issue of crime created an opening for unfiltered, fear-based messaging.

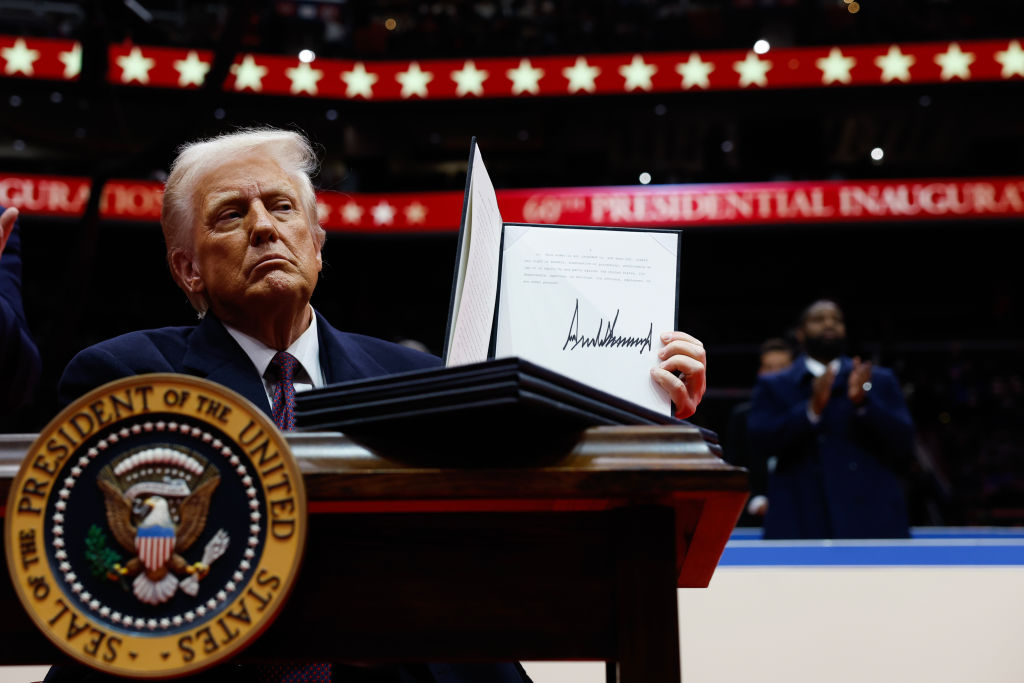

A true opportunist, Trump seized on this momentum, reviving old tough-on-crime themes with unprecedented bluntness. His harsh rhetoric builds on decades of political messaging, but he removes any remaining euphemism or restraint. While past presidents used coded language, Trump prefers overt racism and xenophobia. He has described BLM protestors as “thugs,” undocumented immigrants as “animals,” and claimed that his felony convictions made him more relatable to Black Americans. Trump’s 2017 inauguration speech titled “American Carnage” described a country, as he saw it, in disarray, and signaled his intent to make crime a central fear in public discourse.

But unlike Nixon, Reagan, or even Clinton, Trump often ignores policy details, favoring bold, combative, and offensive statements. Social media allows him to do this in a more raw, unfiltered manner than leaders before him and serves as Trump’s preferred method of communication. He repeatedly exaggerates crime rates and blames Democrat-run cities while simultaneously downplaying January 6 and other violence linked to his own supporters. Trump’s focus on migrant crime and calls for the mass deportation of so-called “illegals” mirror past racialized narratives but place a greater focus on crime: He views the mere existence of these people within our borders as criminal.

Trump has gotten away with such controversial rhetoric for his entire political career, in large part because his supporters seem not to care. At an Iowa campaign stop in 2016, Trump quipped that he could “stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot someone” and his supporters would stand by him. His comeback win in 2024, amidst felony fraud convictions and a doubling down on racist rhetoric, certainly supports his claim. So, while in practice Trump’s policies align with previous tough-on-crime leaders, his real innovation is rhetorical: By addressing crime in a more overtly racist manner, Trump has amplified the strategy of fear-mongering and solidified crime as a cultural and political weapon more than ever before.