It was January 2008 when Luz Marina Bernal’s life changed forever. Her son, Fair Leonardo Bernal, a 24-year-old with cognitive disabilities, left their home in Soacha, Colombia, in search of work. He never returned. She would only find more information about her son’s disappearance that August, when the Colombian military told her that his body had been found in a mass grave in Ocaña, buried alongside 18 others. They told her that her son “was a guerrilla leader and had been killed by the army in combat.” Bernal knew then that it was a lie; it would take years for anyone else to find out.

Fair Leonardo was just one of thousands of innocent civilians murdered by the Colombian military and later passed off as enemy combatants—a scandal that would become known as the “false positives.” The modus operandi was particularly cruel: Civilians were lured by a “recruiter” under the false pretense of job opportunities and taken to remote locations. There, they would be killed by members of the military—the scene subsequently manipulated to make it appear as though the person had been killed in combat. They would photograph this, inconsistencies and all, to keep a record of each “success.”

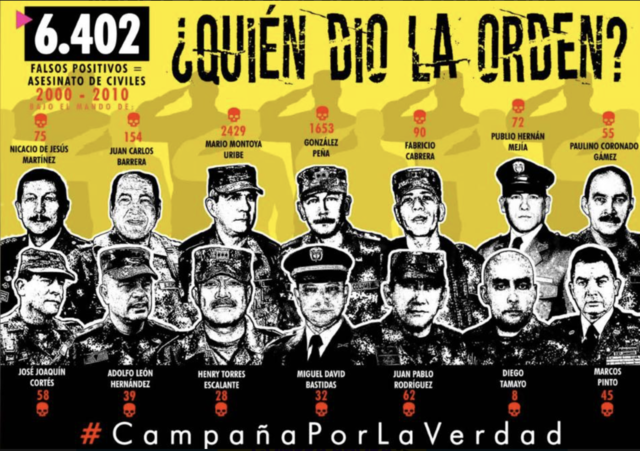

According to Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace, more than 6,000 civilians were killed this way between 2002 and 2008. The first victims, uncovered in 2008, were 19 men from Soacha, a municipality outside of Bogotá, whose bodies were found in Ocaña, Norte de Santander. As more bodies were discovered, however, it rapidly became clear that the government-led killing of civilians was not limited to a department or region.

The victims were young farmers from Huila, taxi drivers from Neiva, unemployed Bogotanos, and even minors from Cesar. It is no coincidence that most victims resided in high-poverty communities or rural areas—those in greatest need of protection by the state were the systematic targets of a crime committed by the state itself.

Years prior to the discovery of the false positives, then-President Álvaro Uribe launched his Democratic Security policy. Made official in 2003, it consisted of efforts to achieve a “gradual consolidation of state control over the entire territory” and protect civilians by dismantling guerrilla groups and reducing kidnappings and homicides. As defense budgets ballooned, an informal reward system emerged: Soldiers were rewarded for each “combat kill” and civilians were paid for information that led to deaths. The results looked good on paper: kidnappings, extortion, and rural violence dropped. Yet the same regions that appeared safest were those where the most civilians were executed. A lack of oversight and the greed built into result-driven policies led to one of the gravest violations of Colombians’ rights in recent history.

For years, the killings might have gone unnoticed if not for the persistence of a group of women, including Bernal, who became known as the Mothers of Soacha. Their activism began at the local level, following the discovery of the first bodies—pressuring municipal leaders, filing complaints, and gathering in public squares with photographs of their children. Over time, their voices grew louder, reaching national television and greater media coverage. Their initiative grew from social leadership within their communities to filming documentaries and taking over theatrical stages in countries around Latin America and the world at large.

Visibility came at a cost: The more their movement grew, the greater the threats they faced. Bernal herself was told bluntly, “You haven’t understood the message. Face the consequences.” It was a warning meant to deter her activism and inquiry on cases like her son’s. Though she never learned who sent the threat, her experience reflects a broader truth: In Colombia, seeking justice is a dangerous act. In 2023 alone, 181 social leaders and human rights defenders were murdered, and by mid-2025, the toll had already reached 81. Despite the danger—and the state’s failure to protect them—the Mothers of Soacha pressed on, ensuring the false positives became not just a whispered rumor but a national scandal that captured worldwide attention.

International human rights organizations also amplified the mothers’ demands. UN rapporteurs documented the patterned nature of the crimes, building a case against the state. Amnesty International supported the movement by closely studying Colombian politics; they warned that proposed constitutional reforms could cement military impunity.

At first, the government dismissed the mothers’ claims. Then-President Uribe implied that the dead were criminals, not civilians who went out “to pick coffee.” Defense Minister (and later President) Juan Manuel Santos expressed disbelief that army units could possibly be demanding “results, as bodies.” By distancing himself and the state from any direct responsibility, Santos downplayed the scale of the crimes, portraying them as isolated incidents rather than part of a systematic practice. In 2011, an ex-soldier’s testimony questioned this long-held belief, exposing the possible systemic nature of the crime. He stated that “the ones who gave the order were Lieutenant Ovalle and Lieutenant Mora,” two high-ranking officials in the army. Other testimonies given by two captains of the army accentuated the premeditated and organized reality of the killings.

As evidence mounted, the official line shifted. Soldiers were expelled, generals reshuffled, and apologies offered. What began as cases being handled within the Army’s judicial branch, with no true justice, turned into a rapidly escalating series of confessions that indicted the highest ranks of Colombian military personnel. As more information came to light, public awareness of the atrocities orchestrated by their own military grew, yet prosecutions largely stopped at the rank-and-file, while higher-ups escaped with careers intact. This scandal broke only towards the end of Uribe’s second term of presidency, though later investigations revealed that most killings had taken place throughout his presidency. While low-ranking soldiers were prosecuted, senior officers and political leaders remained largely untouched. By the time public outrage began to take hold in the early 2010s, the damage was already done—Uribe left office with approval ratings of 75 percent, a testament to how state violence could coexist with popular legitimacy. Still, while much of the public focused on declining insecurity rates, the Mothers of Soacha intensified their fight. In 2010, as Uribe left office, they brought their case before national and international institutions, demanding justice and state accountability. Their persistence kept the scandal alive, eventually leading to a 2015 complaint against Uribe himself after he accused their children of being criminals.

Some Colombians defended the army, framing investigations as an attack on national security. Analysts warned that prosecuting soldiers would weaken the fight against guerrillas. The official denial and consistent disconnection between lower-rank soldiers and higher-ranking officials created a veil of protection for the system and top-ranking politicians. This allowed for the creation of a strong political base that, with a 40 percent decrease in the homicide rates and increased perceived safety, swore support to Uribe. His alliance with powerful states like the United States reinforced international support for his policies, granting him legitimacy both at home and abroad.

This September, the first sentencing related to the false positives was concluded by Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP). Unlike earlier prosecutions that treated the killings as isolated abuses, this ruling recognizes them as part of a coordinated, systematic practice carried out under state authority. That it is happening now matters because it finally acknowledges the false positives not as independent instances, but as a collective crime rooted in institutional policy.

More than two decades later, justice for the false positives remains unfinished, and the struggle for memory and accountability continues. In November 2024, the mothers of victims—including Bernal—who have yet to find the truth about what happened to their sons, placed an exhibition of boots in Rafael Núñez Square, a known landmark in Bogotá, in memory of the 6,402 lives lost. In response, far-right Congressman Miguel Polo Polo threw the boots in a trash bin and declared the demonstration propaganda. Polo Polo argued that the claimed number of victims had been “inflated” despite the fact that several sources corroborate it as a conservative estimate. Colombian society, wrecked by internal conflict for more than 50 years, continues to grapple with a polarized social memory of the false positives and a brittle peace.Luz Marina Bernal continues leading the work of the collective, setting up exhibitions nationwide to remind everyone that the mothers did indeed know best, and that they will keep fighting until the very last victim sees justice.