At 8:30 a.m. on August 9, 2018, an aerial bomb fell on a school bus in a market in Yemen, killing 40 children. The explosion was so powerful that some parents could not even find a trace of their children’s remains. That same day, a lawyer identified markings on a guidance fin from the bomb’s casing: Lockheed Martin had manufactured the bomb in Garland, Texas. This now-infamous tragedy was just one of many war crimes committed by the Saudi-led coalition in the Yemeni Civil War using weapons and intelligence purchased from the United States.

After almost six years of attacks like these, President Joe Biden recently announced a plan to end US support for Saudi Arabia’s offensives in Yemen and voiced his desire to end the war. He also vowed to halt any “relevant arms sales,” and reversed the Trump administration’s designation of the Houthi groups as a foreign terrorist organization. Biden also appointed a special envoy to Yemen to boost conflict mediation and diplomatic efforts. However, while all these moves look promising on the surface, Biden’s policy for Yemen actually needs much stronger commitments—namely, a more complete withdrawal of all US support from all coalition members—in order to make any real progress toward peace.

The conflict in Yemen has deep roots, but it has raged most fiercely since the Houthi rebels took the capital of Sana’a from the Yemeni government in 2015. Saudi Arabia formed a coalition against the Houthis, and Iran has been supplying the rebels with arms, turning it into a proxy war between regional powers. Seeking to combat Iranian influence in the region, the US has supported the coalition with intelligence and weaponry. Both sides have targeted civilian food and energy infrastructure and obstructed or diverted humanitarian aid going to the areas they control. As a direct result, 13.5 million Yemenis are food insecure, and thousands are starving to death.

Various human rights activists celebrated Biden’s decision as a welcome change in tone, compared with the previous administration’s stubborn support for the Saudi military intervention. Yet many also speculated that it had come too late and would take several years to make a significant impact, as the US has already supplied billions of dollars’ worth of arms to the conflict. Farea Al-Muslimi, a researcher focused on the region, called the decision “symbolic in a lot of ways.”

The Biden administration’s new policy is not without its caveats. In the same speech announcing cuts to Saudi offensive aid, Biden promised to continue to help Saudi Arabia “defend its sovereignty” against the Houthi rebels. Since Saudi Arabia frames its entire intervention in Yemen as “defensive,” there is still significant room for interpretation as to what the US will or will not support. The president also did not clarify what arms sales his administration will regard as “relevant.” In addition, it remains unclear how the government will deal with Qatar, which recently re-joined the coalition and could begin providing arms or even troops to the conflict. In light of all this, it is no wonder that Saudi officials reacted much less negatively to the announcement than one might expect, even saying that they “welcome” the promise of continued defensive support. Perhaps they understand that these caveats will leave Biden plenty of room to maintain the status quo.

In truth, this announcement which may look promising to opponents of the war in Yemen could turn out to be little more than paying lip service to President Biden’s campaign promises. He will need to show a stronger hand to Riyadh if he hopes to make any progress toward a ceasefire. However, now that he is in office, Biden may be more reluctant to jeopardize the U.S.-Saudi relationship given the various interest groups which have maintained it over the past 70 years. Specifically, the US relies on Saudi counterterror intelligence, weapons sales, opposition toward Iran, and (of course) its oil.

US counterterror officials have emphasized the role that Saudi Arabia plays in fighting al-Qaeda and other extremist groups. They point to a 2010 thwarted terror attack which Saudi intelligence helped prevent, among other cases. The weapon-manufacturing lobby, of course, supports the hundreds of billions of dollars in arms deals with the kingdom. Security hawks want to maintain U.S. influence in Yemen to keep Iran from securing greater influence in the region through the Houthi rebels. And while the U.S. has become more energy-independent in recent years, it still relies on Saudi Arabia’s economic cooperation. Riyadh reminded Washington of this fact last year when they flooded the oil market and damaged America’s shale gas industry.

These various pro-Saudi interests may explain why Biden’s rhetoric was more muted than it was on the campaign trail, where he promised to turn Saudi Arabia into an “international pariah.” He also signaled his willingness to capitulate to Saudi interests by deciding not to punish Prince Mohammad bin-Salman for his killing of Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist. However, in order to make any progress toward peace in Yemen, Biden will need a much stronger stance than his current Yemen policy. Both sides of the war have committed too many atrocities against civilians to merit any U.S. support, offensive or defensive.

The best policy in Yemen at this point would be to revoke all military and intelligence support for all members of the coalition. The administration could then focus more on humanitarian aid, which is falling far short of its funding needs. Only a concrete stance like this one would allow the U.S. to mediate the conflict, encouraging both sides to open ceasefire negotiations or at least to allow humanitarian aid to reach those in need.

In reality, President Biden has full power to override the interest groups tying America to the Saudi kingdom and its war, he just needs to see it through. Gerald Feierstein, a former US diplomat to several countries in the region, called the US-Saudi alliance “a relationship that’s kind of a mile wide and an inch deep.” After Saudi Arabia flooded oil markets, conservative members of Congress finally began to reconsider their high regard for the kingdom, meaning cutting ties could have bipartisan support. The argument that America must stay in Yemen to counter Iranian influence is losing power now that this intervention, which Saudi Arabia originally predicted would be over in months, has dragged on for 6 years. Meanwhile, the Houthis only continue to gain ground. In addition, counterterror officials are hard-pressed to argue that Saudi intelligence is critical to national security given that most terrorists in recent years have been home-grown, not coming in from the Middle East. Considering all this, President Biden is fully capable of getting US weaponry out of the region. He only needs the will to do so.

Long-term peace in the region will require a lot more reconciliation than the United States can initiate alone. However, even a temporary break in the fighting due to US pressure would at least be enough to reach more Yemenis with aid and allow them to start rebuilding some infrastructure. That alone could save thousands of lives, and is well worth the effort. The conflict in Yemen is the direct cause of one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. Over 230,000 Yemenis have already died from the war, half of them from indirect causes such as lack of food and medical care. There is no room in this situation to capitulate to corporate interests or myopic counterterror officials. President Biden must unequivocally end support for the Saudi-led coalition and apply strong pressure to both sides to come to the negotiating table so that the US will no longer be complicit in the suffering in Yemen. If America still claims to represent peace and democracy, it must start applying those values to its policy in the Arabian Peninsula as well.

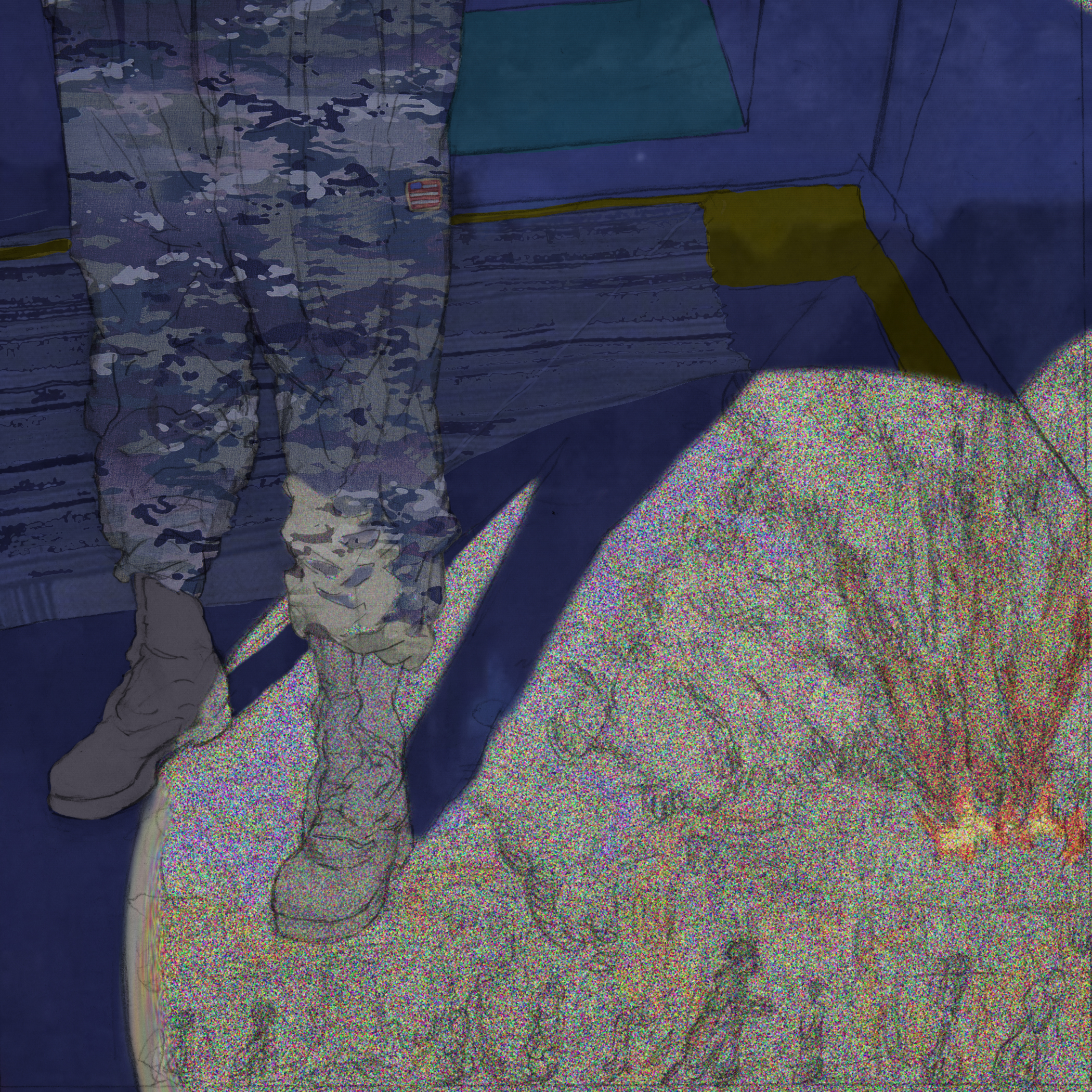

Illustration by Josh Sun