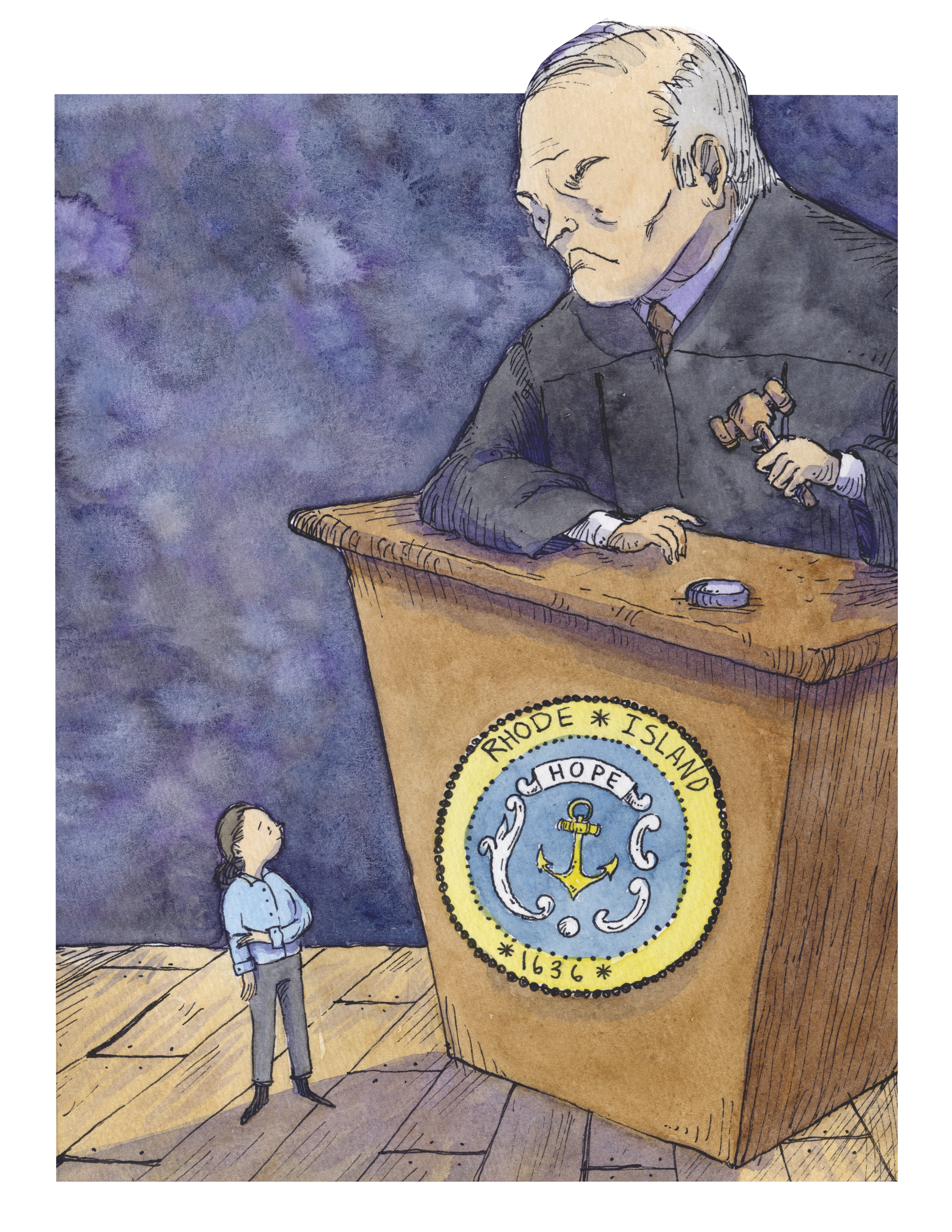

If you experience domestic violence, a victims’ compensation fund should defray the medical and legal costs of victimization. If you are deemed the wrong kind of person, however, Rhode Island’s victim compensation fund will turn you away. Rhode Island is one of only seven states that ban people with criminal records from receiving assistance from victim compensation funds, alongside Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Ohio. Despite its reputation as a progressive state, Rhode Island is out of step with other liberal states when it comes to helping victims of crime who may themselves have a criminal record. For a state whose motto is “Hope,” denying compensation based on criminal history is unacceptable. Reforming these policies is crucial for all victims to receive the help they need.

Victim compensation funds exist in all 50 states and are important sources of relief for people who have experienced the trauma of a crime. The federal government supports 75 percent of the funding, and states provide the remaining funds, typically through fines and fees levied on criminal defendants. Victim compensation funds commonly provide relief for often substantial medical and burial expenses that are not otherwise covered by a victim’s insurance.

Victim compensation funds do not just help current victims: They may also stop cycles of violence and prevent the creation of new victims in the future. A report from the Center for American Progress notes that people are less likely to commit harm against others if they receive the support they need to heal from their own victimization.

However, the process of obtaining victim compensation is challenging. According to a 2022 poll conducted by the Alliance for Safety and Justice, 96 percent of victims of violent crimes across the United States were not given support from victim compensation funds. Fewer than 50 percent of crime victims and survivors submit reports to law enforcement about what happened to them, precluding their ability to obtain compensation in most states. Many are unaware that victim compensation funds are an option for them; even if they are aware, many lack the necessary resources to apply for the funds because the application requests an abundance of often difficult-to-find information. In fact, just over 6 percent of people who were victims of crime actually applied for compensation in 2023.

The distribution of victim compensation is often based on subjective views of law enforcement about who deserves help rather than the objective strength of a case of victim need. The many hurdles to obtaining relief exacerbate the obstacles victims already face in recovering from their trauma. A state committed to recognizing and legitimizing the experience of victims must ensure that it provides compensation without needless bans or so many impediments to relief that victims do not bother with the process of applying.

Despite being known as a relatively progressive state, Rhode Island has some of the nation’s most restrictive rules for people seeking assistance after being victimized. Regardless of the nature of the crime that they have suffered from, victims must report it to the police within 15 days. Those with a violent conviction in the past five years, or any criminal record at all, may be denied relief. The legislature of Rhode Island even rejected a proposal to have the state cover funeral costs for victims, whether they had a criminal record or not.

Restrictions on fund access based on prior convictions are especially unforgiving for victims of gender-based violence. Victims of gender-based violence often delay contacting police because reporting their experience can lead to escalated violence in their relationship. If this delay exceeds 15 days, Rhode Island will deny compensation. People—especially women—in abusive intimate relationships may be coerced into aiding and abetting their abusers’ crimes, thereby obtaining a criminal record. Of the 24 percent of relationships that involve violence, almost half involve reciprocal violence, where both parties might find themselves with criminal records, but the relationship is characterized by a power imbalance where one of the parties is driving the abuse. If those coerced partners or the vulnerable party in a reciprocally violent relationship seek compensation for the violence they have experienced, they will not receive aid from Rhode Island’s fund.

These bans also disproportionately harm Black communities. Black Rhode Islanders may have an augmented number of prior records because of structural barriers to employment, housing, transportation, education, and healthcare, coupled with discriminatory policing practices that target their communities to a higher degree than others. Despite making up 14 percent of the population and being equally likely to use drugs when compared with white people, Black people make up one in four of those who are arrested for drug-related crimes. Black Americans are 5.9 times more likely to be incarcerated than white Americans. In Rhode Island, Black people make up 15.3 percent of the population, but they accounted for 33 percent of all arrests in 2019. A ban on people with criminal records thus ends up targeting people of color, compounding existing inequities.

Rhode Island’s victim compensation system equates a person’s past mistakes with present guilt, effectively blaming victims for their past and not allowing them room to grow after subsequently facing harm themselves. It is time for Rhode Island to join states like Illinois, Maryland, and New York that have reformed their victim compensation regimes in the last four years. Maryland and New York no longer require victims to make a police report to receive compensation. A referral from a social service provider to the victim compensation fund can be sufficient, thus helping those victims (especially those who have experienced intimate partner violence) who are reluctant to go to the police. As a state that prides itself on progressive values, Rhode Island should be joining the states that are leading on this issue because it is also a matter of racial and sexual justice.

Rhode Island should reconsider its ban on individuals with criminal records, allow victims to report their harms to service providers other than the police, and make sure its victim compensation application process is user-friendly. Enacting these measures will help break cycles of violence and harm. When it comes to providing relief for victims, Rhode Island unfortunately stands out as one of the few states to punish crime victims for their past. Rhode Island should reform its compensation regime and join other states that are leading the way by compensating victims regardless of their criminal records. In doing so, they would recognize that even those with past convictions can suffer victimization and should receive help.