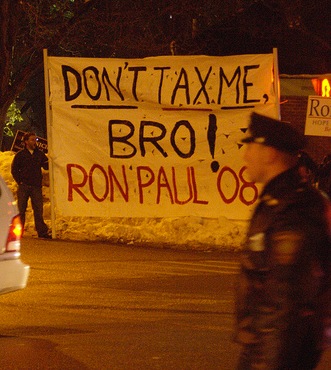

A strikingly common cornerstone of right-libertarianism (and, correspondingly, the modern American libertarian movement) is the assertion that “taxes are immoral.” This argument can take a number of forms, some significantly stronger than others. I wish to address two of the formulations of this argument that have appeared in recent articles in different publications on the Brown campus and from this, hopefully eke out what a sounder formulation of this argument would entail.

A strikingly common cornerstone of right-libertarianism (and, correspondingly, the modern American libertarian movement) is the assertion that “taxes are immoral.” This argument can take a number of forms, some significantly stronger than others. I wish to address two of the formulations of this argument that have appeared in recent articles in different publications on the Brown campus and from this, hopefully eke out what a sounder formulation of this argument would entail.

A weak form of this argument appears in Oliver Hudson’s article for the Brown Daily Herald, “Universal Suffrage is Immoral.” It appears not explicitly but in the course of his larger argument which I have no interest in even beginning to refute here. The crux of the argument is that taxes are roughly morally equivalent to theft.

Hudson tries to make this sort of argument by appealing to a common moral intuition, stating: “most would agree that controlling how your neighbor or friend spends his or her money is morally wrong.” This assertion is uncontroversial. However, the assertion that follows is less so. Hudson continues: “if you went to your friend and told him you’re taking his money to donate to charitable causes “for the good of the public” that would be fine? It is noteworthy that we call one case stealing and the other taxation, but they are effectively the same.” A parallel argument would run something like this: “if you caught someone forging a check of a value greater than $500 and imprisoned him in a room in your house for four years that would be fine? It is noteworthy that we call one case illegal kidnapping and the other justified punishment, but they are effectively the same.”

It is not exactly noteworthy that there are actions that a government can take that we would definitely not allow any individual citizen to commit. This could be for a number of reasons, but the primary idea seems to revolve around the fact that there is a robust system of checks and balances that limit when a government can and cannot do something like the removal of funds from a person or restricting their freedoms through imprisonment. This robust system of checks and balances, at least theoretically, means that any action taken on the part of the government must have a much stronger underlying rationalization than the actions taken by any individual. Allowing any given individual to remove funds for the common good or imprison another individual for violation of the common good under his own judgment gives us no guarantee that his judgment will be sound, nor that the common good will be served via the extraction of those funds or that person’s imprisonment. Of course, there is the possibility that any particular instantiation of self-limiting functions of government might be flawed, but it does not follow from this that all conceivable functions of government are flawed likewise.

A stronger version of this argument which appears in Benjamin Koatz’s article “His Holiness and State Sponsored Violence” runs like this: “Taxes are involuntary. If you don’t pay your taxes you go to jail. Police steal you away and put you in a cell, by force. Meaning, that government programs are funded at the point of a? [sic] Gun.” In context, the argument fixes around the Dalai Lama’s rejection of violence and I think, for the sake of fairness, a similarly complete rejection of violence as a means should probably be assumed. To be honest, I am unsure what the Dalai Lama’s stance on the use of violence in self-defense or to defend others is, however, I would think that most people without a radical religious or philosophical stance would probably agree that there are certain limited cases where violence is permissible.

Even if we concede that violence is never justified it does not necessarily follow that use of force is never justified as it is not exactly clear that all force is violence. The most salient illustration of the issue is a parent walking next to a busy street with a child. The child, excited by something on the other side of the road, runs into the street and his parent grabs him by the arm to pull him back. This is certainly a use of force as the parent grabs the child’s arm and physically moves him back onto the pavement, but only an incredibly loose definition of violence would include this act. Furthermore, any definition of violence which includes this act would seriously cast doubt on the idea of all violence being morally wrong as this action hardly seems to be wrong. This particular example seems to illustrate that there are certain situations where the use of force is justified in order to prevent harm from befalling someone.

Even if we concede that violence is never justified it does not necessarily follow that use of force is never justified as it is not exactly clear that all force is violence. The most salient illustration of the issue is a parent walking next to a busy street with a child. The child, excited by something on the other side of the road, runs into the street and his parent grabs him by the arm to pull him back. This is certainly a use of force as the parent grabs the child’s arm and physically moves him back onto the pavement, but only an incredibly loose definition of violence would include this act. Furthermore, any definition of violence which includes this act would seriously cast doubt on the idea of all violence being morally wrong as this action hardly seems to be wrong. This particular example seems to illustrate that there are certain situations where the use of force is justified in order to prevent harm from befalling someone.

In conjunction with this previous point, it seems notable that we generally consider people to have a moral obligation not just to refrain from doing harm to others, but also to prevent harm from befalling others if the cost to them is negligible. For example, if an able-bodied individual was to come across a quadriplegic who had fallen into a shallow body of water and was now drowning for lack of ability to remove themselves and the able-bodied individual could prevent the death of the quadriplegic at the cost of merely getting his sleeves wet, not helping said quadriplegic would be morally wrong. If this is the case and we accept that force is sometimes justified to prevent harm from befalling an individual as illustrated above, then it does not seem that one would be incredibly remiss to create a statute, which, by force of imprisonment or fine, would obligate able-bodied people to help mitigate possible harm to others whenever the cost to them would be negligible. How the argument follows from here should be relatively clear. People with large amounts of money can, without question, sacrifice an amount of their holdings with no noticeable effect to their quality of life nor to their physical person while this same negligible sacrifice could literally prevent people from dying whether it be from starvation or preventable illness.

The objection to this point runs something like this: yes, this is all well and good, but that money is the rich person’s property. How can we ever justify violating his right to his own property? The problem with this objection is that it automatically glosses over an entire (quite interesting) issue: what does it exactly mean to say that something is someone’s property? Or, more specifically, what relationship must one have to something to say that they have an inalienable right to the possession of something?

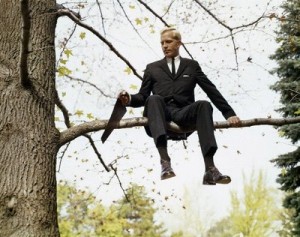

The Lockean model of property ownership as an extension of the right to personal sovereignty in the form of labor is a compelling one and is generally, I think, the one that runs implicitly in most discussions of property. If we own our labor, why should we not own the products of our labor as well? But as Locke recognized, this model cannot hold in the face of scarcity. The right to property is not the sole existing right, we recognize, at the very least, a right to life as well. And, in most cases, this right is far more fundamental (and far less controversial) than the right to property. Consider a group of people traveling through a desert, the strongest and fastest comes upon a fruit tree and picks all of the fruit for himself, he has technically mixed his labor with the fruit, but to assert that he has an absolute right to dispense with the food as he will is to say that his right to property is more important than the other individuals’ right to life. I cannot think of a way to justify this conclusion, and to do so requires an incredibly strong argument as it flies so intensely in the face of our moral intuitions. On the other hand, if there was exactly enough food for one individual to survive, there would be a strong moral argument for the fastest to keep the fruit of the tree. However, this does not stem from his right to property qua property but instead to his right to property insofar as it enables him to continue living. He does not have an obligation to give up goods that he needs to survive in order that others might, but he does not have a right to stockpile food if others might die.

The Lockean model of property ownership as an extension of the right to personal sovereignty in the form of labor is a compelling one and is generally, I think, the one that runs implicitly in most discussions of property. If we own our labor, why should we not own the products of our labor as well? But as Locke recognized, this model cannot hold in the face of scarcity. The right to property is not the sole existing right, we recognize, at the very least, a right to life as well. And, in most cases, this right is far more fundamental (and far less controversial) than the right to property. Consider a group of people traveling through a desert, the strongest and fastest comes upon a fruit tree and picks all of the fruit for himself, he has technically mixed his labor with the fruit, but to assert that he has an absolute right to dispense with the food as he will is to say that his right to property is more important than the other individuals’ right to life. I cannot think of a way to justify this conclusion, and to do so requires an incredibly strong argument as it flies so intensely in the face of our moral intuitions. On the other hand, if there was exactly enough food for one individual to survive, there would be a strong moral argument for the fastest to keep the fruit of the tree. However, this does not stem from his right to property qua property but instead to his right to property insofar as it enables him to continue living. He does not have an obligation to give up goods that he needs to survive in order that others might, but he does not have a right to stockpile food if others might die.

And this is the question that staunch tax opponents must answer: what could possibly give an individual the right to stockpile goods above and beyond his personal needs when there are others suffering for lack of them? A mere appeal to the right to property is not enough, as the right to life is generally considered the most fundamental. The government exists for many reasons, but the most primary is to protect the interests of those it governs. It is definitely in the interests of the poorest among us to not starve or die from preventable illness and when the cost to stop these things is so small as to be literally unnoticeable for the richest among us, there must be an incredibly strong ontological justification for the existence of a property right stronger than the right to life.

And this is the question that staunch tax opponents must answer: what could possibly give an individual the right to stockpile goods above and beyond his personal needs when there are others suffering for lack of them? A mere appeal to the right to property is not enough, as the right to life is generally considered the most fundamental. The government exists for many reasons, but the most primary is to protect the interests of those it governs. It is definitely in the interests of the poorest among us to not starve or die from preventable illness and when the cost to stop these things is so small as to be literally unnoticeable for the richest among us, there must be an incredibly strong ontological justification for the existence of a property right stronger than the right to life.

All the preceding arguments are not meant to illustrate that taxes are a distinctly moral institution. And it should go without saying that taxes not being a moral institution does not mean that they are an immoral one. There are many things which exist which are outside the scope of morality entirely (e.g. traffic laws). These sorts of things merely exist out of organizational efficiency, i.e. we get better outcomes from having traffic laws (or, possibly, taxes) than if we do not. In order to deduce the conclusion that taxes are positively immoral there are some underlying claims which must be put forth quite strongly. These claims are: first, a moral theory that asserts that all uses of force (except, possibly, to prevent another use of force) are immoral. Second, a theory of government which can exist while utilizing exactly zero force (except, again, possibly to prevent another use of force.) And finally, a theory of property rights so robust that it can: a) justify the accumulation of property far beyond what one human being could use, b) establishes said rights as more sacrosanct than the right to life in order to establish c) the right to dispose of that surplus property however one wishes even if people starving and dying as a consequence and d) exist without recourse to any form of codified force used by the government or justify the use of force to protect property (possibly by establishing theft as a use of force).

This is no small task, but claims of immorality (or morality) are large claims. I do not think that I could construct anything resembling such as system under any existing moral theory, but perhaps that says more about my cognitive abilities than the difficulty of the argument. Regardless, if anyone feels up to attempting this herculean task, good luck.