The first mental illness attributed to women, and one of the most prolific for four millennia, was so-called “female hysteria.” An amalgamation of symptoms that would be considered both mood and personality disorders in the modern Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders were readily compressed into this exclusively female diagnosis. “Female hysteria” was used to rescind agency from women diagnosed. Today, these same symptoms are found in possession-trance religions: largely affecting women, yet resulting in a far different balance of power.

The first mention of hysteria is found on the Kahun gynecological Papyrus, an ancient Egyptian scroll dating back to 1900 BCE. The treatise described nervousness, fainting, and insomnia as a part of the female disposition. Early interpretations of the Papyrus believe this to be the result of a “wandering womb,” the idea that the organ would be displaced within the body due to lack of use. A social belief rather than an exclusively religious one, this diagnosis reinforced the idea that women existed solely for the purpose of reproduction, and the detriment that could befall everyone if this was not adhered to. In the 5th century, Hippocrates brought this diagnosis to Western medicine, giving hysteria its nomenclature in Diseases of Women from the Greek word for uterus, hystera. The identified cause of hysteria reflected the androcentric nature of the medical field, as the Socratic philosopher went on to argue that a major cause was a woman’s withholding of sex from their male partners. Plato treated hysteria with regular marital sex, a prescription which reflects the broader objectification of women and centering of men within medical practices, a positing that continues to this day with infamous examples like “the husband stitch.” Women were generally not treated as patients and victims of mental illness. Rather, they were a cause of far greater suffering: unfulfilled male sexual desire.

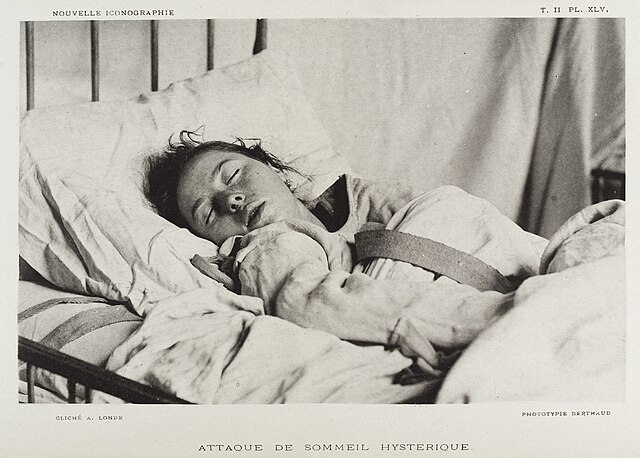

With the recognition of mental illness and the psychological discipline in the 19th century came a shift in the societal attitude toward female hysteria. Charcot and Freud framed hysteria as a neurological and psychological condition respectively and were the first to diagnose it indiscriminately of gender. This came with a rebranding: the term “neurasthenia” served as a more scientific classification of hysteria. Still, women were institutionalized at far higher rates due to neurasthenia diagnoses, particularly after the establishment of state-run psychiatric asylums in 1845 in the United Kingdom and then five years later in the United States. In England and Wales, 31,822 out of 58,640 “certified lunatics” in 1872 were women. In extreme cases, female-presenting patients were even forced to undergo surgical hysterectomies.

While it may not be wrong to view hysteria as a female illness, this connection is not because of anatomical reasons. Instead, the diagnosis may be a socially induced gender disparity rather than a biological one. The field of psychiatry was established and codified by men from its inception, inevitably ingraining gender roles and ideals of the time. As Elaine Showalter, author of the Female Malady, argues, “In a society that not only perceived women as childlike, irrational, and sexually unstable […] but also rendered them legally powerless and economically marginal, it is not surprising that they should have formed the greater part of the residual categories of deviance…” With this in mind, female hysteria makes the political personal, serving as an outlet for suffering at the hands of patriarchal exploitation.

However, there are cases where female distress becomes not a manifestation of subjugation, but a tool to combat it. This occurs in socio-political climates where women are almost entirely disenfranchised, resulting in an antithetical collective fate to women in distress. Examining this presents a juxtaposition exposing how female political influence is both silenced and elucidated. Clear examples of this can be found in possession-trance religions in Northern and Central Africa. Spirit possession, while common in many world religions including Hinduism and Christianity, takes on a vital role in many animist and Islamic African religions. Symptoms of these trances are similar to those of hysteria, including hallucinations, seizures, and respiratory distress.

In Sudan, women who display these are considered part of the Zār Ṭambura, an amalgamation of indigenous animist African beliefs and ṣūfī piety (a mystical branch of Islam). Within the Zār Ṭambura religion, spirit possession is a central tenet: Zār translates roughly to spirit and almost exclusively involves female bodies as conduits. Spirits enter these women and cause illness, which can only be cured by the husband appeasing the spirit’s demands. This frequently includes the acquisition of material needs, such as clothing, for her and any children involved in the familial structure. A particularly researched case of Zār possession struck a girl on the day of her wedding—though the dowry had been paid—and prevented the union from moving forward. The spirit had to be appeased and the engagement was broken, albeit with an agreement to pay the dowry back in installments while keeping the furniture for the family.

Zār possession is an inherently gendered torment: the greatest threat of spirit possession is permanent infertility, a belief that indicates the constraints of female power while paradoxically enabling female influence. This element is similar to hysteria, as female predominance in distress states has been recorded by anthropologists globally. Zār possession sanctifies women as the financial decision-makers for the family unit, granting them control over the most historically male sphere of influence. Zār practices directly contrast the Western treatment of hysteria-ridden women, who are stripped of any economic control.

The Puna of Congo-Brazzaville see spirit possession with a benevolent lens, viewing it as a form of divine intervention for the greater good of the society. Bayisi, water spirits, are believed to almost exclusively use women as a medium to enact communal policy. This is also a more conscious act, as during collective song and dance women’s minds are “opened up” to the “maternal universe.” Here, the Bayisi may enter them whenever the community requires intervention for its well-being. During religious ceremonies in front of political leaders and elders, the spirit is thought to speak through possessed women who then temporarily serve as policymakers.

This rapid political enfranchisement is a direct result of possession, once again inverting the ramifications of female mental distress in the West and particularly the United States. The potentiality of mental health crises in female political leaders are often cited as reasons for their lack of credibility. During Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign, the head of the Republican Party said it was legitimate for a “’conservative political operative’ to publicly question whether Ms. Clinton has brain damage and whether she’s covering up other health issues.” Accusations around the illegitimacy of female political power due to “hysterics” harks to the long history of medical subjugation, and further contrasts the political and economic power gained from the possession-trance paradigm.

There are unique dimensions to the Zār and Bayisi enfranchisement as the Zār Ṭambura and Puna are collectivist and non-capitalist communities. These communal and relatively isolated societies are far more homogenous and spiritual, facilitating possession-trance centrality. Under these conditions, exhibits of female suffering grant greater power in relationship dynamics and leadership positions within political institutions.

The contrasting treatments of female mental distress in Western and African contexts reveal the complex ways in which gender, power, and societal structures intersect with perceptions of mental illness. While hysteria in the West has historically served as a tool of patriarchal control, stripping women of agency and economic power, possession-trance religions in Africa provide a striking reversal: female distress translates into political and marital leverage. This juxtaposition underscores the deeply ingrained gender biases within medical and cultural systems, highlighting how societal frameworks can either marginalize or empower women based on the context. As the history of mental health diagnoses evolves, it is essential to recognize the broader implications of how such labels shape the lives and roles of women across the globe.