Last week I missed an important reason why Spain is in a state of absolute disarray. This of course is the growing strength of independence movements, both in the Basque Country (Euskadi) and Catalonia –which may have crossed the Rubicon in its decision to secede from Spain. I have so far avoided tackling the issue for two reasons. First, it is dense, complex, and hard to summarize in a single post. Second, as a Castilian born and bred in Madrid I cannot pretend to be a neutral observer… my gene pool is authoritarian, centralizing, and so forth.

Nevertheless, I’ll take a stab at Houston Davidson’s recent column on Basque and Catalan nationalism. Parts of it are inaccurate. The account of the Catalan bailout is confusing, and nationalism in Spain is not limited to the Euskadi and Catalonia –although it is more widespread in the last two than in Galicia or the Canary Islands. More problematic than all this is Houston’s decision to explain nationalism in Spain while leaving history “for another time.”

Economic realities are obviously important. Catalonia and Euskadi are comparatively wealthy regions that do not want to see their tax revenues redistributed throughout the impoverished south of Spain. Ditto northern Italy and the Mezzogiorno, or Slovenia and Croatia with Kosovo. But if grievances were simply economic, the case would be made for a federal Spain, and not a complete break with Madrid. After all, maintaining your own armed forces and embassies is expensive… and the Spanish state continues to foot the bill whenever Somali pirates hijack Basque fishing boats. Omitting history is no good; one might as well explain the 2008 crisis without a reference to finance, or Walt Disney movies without the disturbing subliminals. Having said that, I am also reluctant to tour five centuries of Spanish history. Bear with me. (Or, alternatively, skip to II.)

I

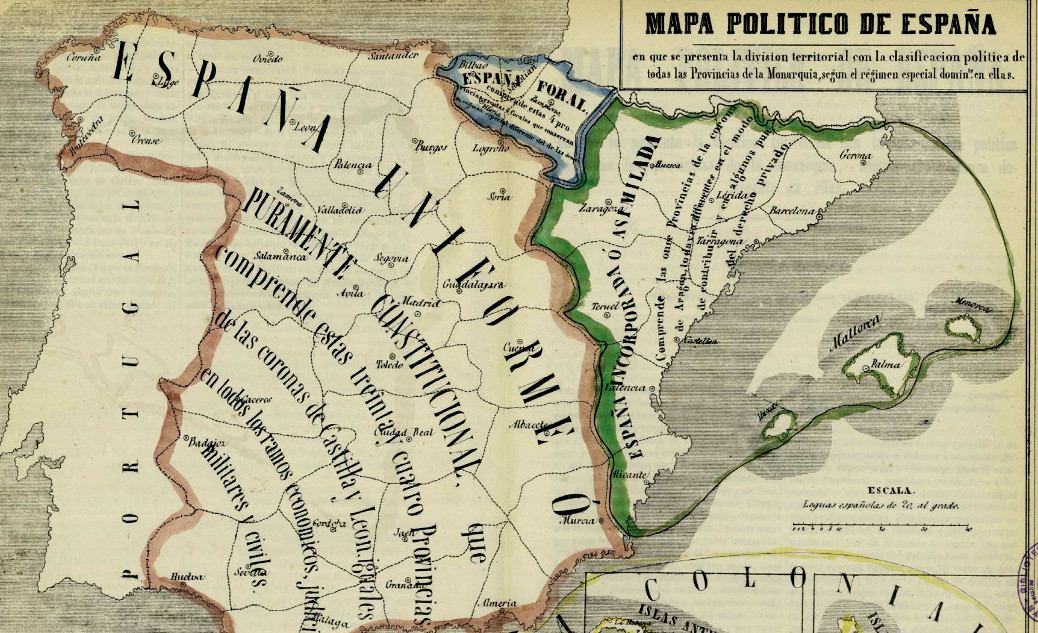

Catalonia and Euskadi each have a culture and language different from those of Castile –the largest region in Spain. These differences can be traced back to Charlemagne and the creation of the Spanish March, a buffer zone between Christian Europe and the Caliphate of Cordoba encompassing most of modern Catalonia and the Basque Country. Catalan language, in fact, has common roots with Occitan and shares similarities with French. This is not the case of the Basque Country, to the extent that the region’s language and people have nothing in common with its neighbors. As Orson Welles put it, Basques are the last aborigines of Europe.

There are three key periods in the history of Basque and Catalan nationalism.

The first traces back to the creation of modern Spain in 1469, through the marriage of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon. Machiavelli’s prince was inspired in Ferdinand: here was the Tywin Lannister of the day, with a ruthless but effective plan to consolidate the Spanish state through religion. This entailed creating the Inquisition and expelling Jews and Muslims from the Iberian Peninsula. Pogroms, ethnic cleansing, and constant paranoia regarding one’s neighbors’ limpieza de sangre; all of this in a society that had been remarkably tolerant under most of Muslim rule, and to this day shares Sephardic ancestry in 20% of its population.

Netanyahu’s father wrote a lot on the subject. Long story short, if Spain did not become the first totalitarian state in history, it was because it lacked the technical means to do so. An ugly story –as nation building tends to be.

Religion, however, was not enough to glue the country together throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Spain, as Gerald Brenan pointed out, became a militarized theocracy. Its monarchs, invested in the power of the Church, were Pharaohs that dominated, but never properly understood, Europe. In a classic case of imperial overstretch, the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) left Spain bankrupt and hollowed out. The attempt to centralize power in Madrid at the expense of Spain’s former kingdoms, followed by a long war of succession, fueled a rise in Catalan secessionism that ended with the siege, bombardment, and occupation of Barcelona by French and Spanish troops on September 11, 1714. The date, which commemorates a defeat, remains Catalonia’s national day.

The second period encompasses the 19th Century. Spanish liberals (in the classical sense of the word) came to power in the aftermath of Napoleon’s occupation, and attempted to modernize Spain. Their agenda was anti-clerical and centralizing, inspired in French Jacobinism. Pitted against a Spanish state of which it had previously been part and parcel, the Church now threw its weight behind Basque and Catalan regionalist greivances, and between 1833 and 1876 three civil wars ensued. The liberals emerged victorious, but the case for regional autonomy was strengthened, with the former Basque kingdom of Navarre becoming a hotbed of regionalist insurgency, and a drive for municipal decentralization that came close to fragmenting the First Spanish Republic into a slew of independent cantons.

The century also witnessed the rise of Romanticism in Europe, and the industrialization of Catalonia and the Basque Country while the rest of Spain remained an agrarian, underdeveloped economy. Where the interest in volk culture met immigration to Euskadi’s industrial core in Bilbao, Basque nationalism was born. As a construct, it was notably different from Catalan nationalism. Where the latter was elite-driven and grounded on existing cultural and linguistic differences with the rest of Spain, Basque nationalism, as formulated by Sabino Arana, developed around a profoundly reactionary ideal of the Basque race, inherently different from, and superior to, that of its atheist, liberal, lazy, effeminate, Untermensch Iberian neighbors –Catalans included. To the extent that Basque elites throughout the period were not nationalist, and Basque language was fragmented, close to extinction, and systematically ignored by Basque writers such as Miguel de Unamuno or Pío Baroja, the race card was the only one left to play.

The final period is Francisco Franco’s dictatorship. Following a civil war between 1936 and 1939, Franco ruled Spain with an iron fist, and attempted to erase all traces of Basque and Catalan nationalism. (Spanish nationalism, on the other hand, was one of the regime’s defining elements.) The repression exercised upon Catalans can be qualified as a cultural genocide, and Euskadi spent the last years of the dictatorship in a constant state of turmoil as the terrorist group ETA answered the regime’s repression with targeted assassinations. Francoism wasn’t just an isolated event, but the culmination of a history of repression dealt by Castile to the remaining nations that composed Spain.

Unsurprisingly, the regime’s brutality encouraged a considerable amount of Catalans and Basques to seek full independence from, instead of more autonomy within, the Spanish state. The shift is still ongoing, and represents an important change in the history of nationalist demands –as Castells points out, the notion of Catalonia as a nation lacking a state was not–up to recently–problematic for most Catalans.

When the dictator died in 1975, decentralizing the Spanish state became a quintessential part of the democratization package. As of today, Catalonia and Euskadi are recognized as “nationalities” in the 1978 Constitution, and both regions enjoy a considerable degree of self-government. It is unclear whether either can seek independence by adhering to the principle of self-determination, to the extent that neither is a former colony nor submitted to any sort of cultural oppression from the Spanish state.

II

To go back to the article, understanding secessionism in Spain requires at least a brief summary of the country’s history. This explains why Catalan and Basque nationalism are different in origins if not in goals, and should not be automatically placed in the same bag. It also sheds some light on what Houston calls the “suspect” notion of “Spanishness.” Basque nationalism appeared only at the end of the 19th Century, and Catalonia has never been an independent nation-state outside of Spain. Spain, in turn, is unlikely to remain Spain without the Basque Country or Catalonia –unlike the United Kingdom without Scotland. It also serves to remind some of the less pleasant aspects of Basque nationalism, such as ETA’s terrorist activity. Now close to being fully dismantled, ETA murdered more than eight hundred Spaniards throughout the last fifty years. Perhaps the organization’s actions could be looked over when they were directed to Franco’s henchmen and torturers, but following the 1977 Amnesty Law it is hard to see them as anything other than senseless murder.

None of this is to deny the history of repression that the Spanish state has exercised throughout its periphery, or the legitimacy of claims to self-government made in light of such abuses. I am equally aware that the current Spanish government, composed by conservatives who are the political inheritors of Francoism, only adds fuel to the fire by disregarding nationalist claims, and attempting to re-centralize the Spanish state in a textbook example of Castilian arrogance and stupidity.

I do, however, remain skeptical of any person who claims to be of the left and nationalist in this day and age. Nationalism seems to me inherently suspect, in its Spanish, Catalan, Scottish, American, and Texan variants. That being said, I would rather see an independent Catalonia than tanks rolling through La Rambla. But the choice is not as drastic as Houston puts it. A federal Spain is (in my humble opinion) the most sensible outcome for everyone.

Perhaps “the most sensible option” is not the de-facto one in times of distress. But I still believe there is much middle ground to be found between independence and oppression.

Love this column. That Houston character’s piece doesn’t hold a candle.

The final point you make about being suspect of nationalism is an engaging one. Perhaps I’m over-reading, but it seems you are picking up on a kind of discursive dissonance, between the cosmopolitan values in left-leaning rhetoric often used as a legitimation device and nationalist reasoning (which is often essentialist, as in your depiction of the basque case). It’s quite possible that there is a way around this tension, though. My bet is that many attempt such a thing.

Finally, thank you for picking up the historical slack. You are 100 % right in this regard.

Here’s an attempt to square the left/nationalism circle.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PuLebpUBCio

Another could be Bolivarianism, which is interesting… But I’m still not sold.

“as a Castilian born and bred in Madrid I cannot pretend to be a neutral observer… my gene pool is authoritarian, centralizing, and so forth.”

I agree