Excerpt from “A Handful of Ash:” “It started out as a film about a practice that has afflicted tens of millions of women worldwide. It culminated in a change in the law.”

Compiling footage from their extensive interviews and research in Iraqi Kurdistan, Shara Amin and Nabaz Ahmed created a deeply moving film, A Handful of Ash. The film provides insight into the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) in Kurdish society and its impact on girls and the greater community. The film was shown in the Kurdish parliament, and has actually impacted law and practice. The numbers of girls being “cut” in these communities has fallen by over 50 percent in the past five years. The success of the film highlights a potential approach to combating FGM in communities around the world.

The nature of FGM in Kurdistan is deeply rooted in tradition and, to some extent, religion. A mullah tells the film-makers that “Khatana [the Kurdish term for FGM] is a duty; it is spiritually pure.” That is the position of the Shafi’i school of Sunni Islam that is practiced by Iraqi Kurds. It is the same branch of Islamic law that is predominant in Egypt, where studies show that up to 80 percent of women have been mutilated.

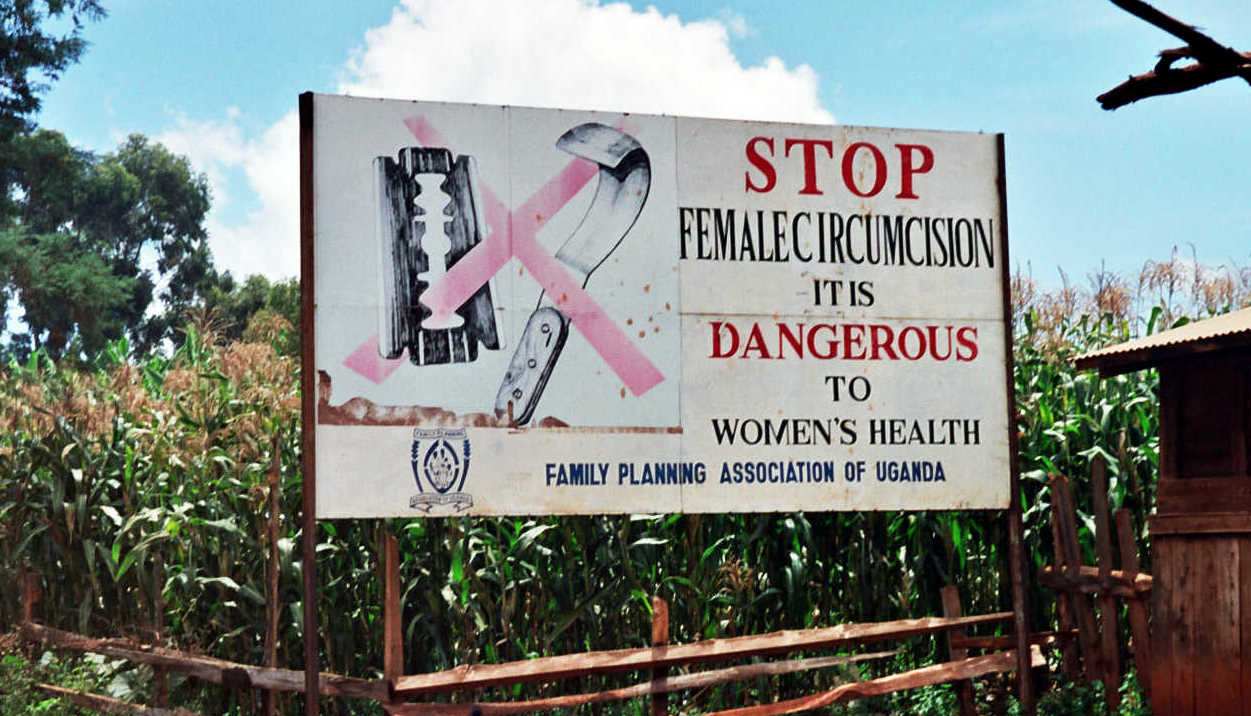

It is not only about religious traditions, however. “It is about controlling women’s sexuality and keeping them under control,” says Nadya Khalife from Human Rights Watch. The film exposes how this practice is harmful and how many religious leaders are now shifting their tone, acknowledging the weak connection between FGM and religious doctrine. FGM is practiced in 29 countries according to the WHO, and is not just confined to some Muslim countries in the Middle East – it is also widespread in parts of Africa and Indonesia.

The actual practice of FGM varies from the cutting of the clitoris in some countries, such as Kurdistan, to removing all external genitalia. Cutting reduces a woman’s libido and is therefore considered necessary for women to remain “chaste,” helping her resist “illicit” sexual acts. The effects of the procedure have much wider consequences, as it puts a woman’s health at major risk. Medical complications often include severe pain, hemorrhaging, infection, and sores in the genital region. The practice also results in severe long-term consequences such as infertility, an increased risk of childbirth complications, and infant mortality. According to WHO estimates, there are around 140 million girls and women worldwide living with the effects of FGM.

The success of the film, as well as a range of organizations and individuals committed to ending the practice of FGM, has made a huge impact. This isn’t to say that the practice is generally declining, or that it will be easy to overcome. One reason for this is that many view FGM as a practice that is part of a tradition and a cultural right that must be respected. While the sentiment seems empathetic and harmless, this mode of thought unnecessarily harms young girls. Another argument has equated female cutting with male circumcision. This is fundamentally wrong, as male circumcision has little or no negative impact on the sexuality or future health of the male. Female cutting has much more severe and harmful consequences. Mutilating young girls is not only physically scarring, but also sets an emotional and mental expectation for a life of submission and obedience. In fact, according to medical experts, “excision of the clitoris is the equivalent of removing the head of the penis”.

Changing minds about FGM and reducing its prevalence is not simply a matter of spreading awareness. The practice of FGM is often rooted in a set of beliefs, values, social norms, and economic pressures that govern the lives of women around the world. In other words, the embeddedness of the practice will make it all the more difficult to eradicate. And although the criticism of FGM raises questions about the right to judge culture and the precarious balance between tradition and modern consciousness, there is no excuse for systematic cruelty towards any group, in any society. In the case of FGM, these cultural arguments come in direct contrast with human decency. Though the practice must be combated in a holistic manner, within its social and religious context, there is never a valid reason to violate a woman’s fundamental right to her own body and her own happiness.

There are certainly valid arguments to be made about the harms and morality of male circumcision. However, there are distinctions between male and female circumcision that make them fundamentally different practices.

FGM is used to control women and their sexuality. In a 1997 joint statement, the WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA declared “FGM to be universally unacceptable, as it is an infringement on the physical and psychosexual integrity of women and girls and is a form of violence against them.” FGM is usually carried out on adolescent or teenage girls who should be legally able to make decisions about their own bodies, unlike male babies.

Furthermore, the WHO notes that “FGM has no health benefits, and it harms girls and women in many ways”, whereas circumcised males, according to the CDC, have lower risk that a man will acquire HIV …and also lowers the risk of other STDs , penile cancer, and infant urinary tract infection.” There are no such benefits to FGM.

This is not to say that things can’t go wrong and there aren’t potential risks involved with male circumcision. However, more serious long-term risks are unlikely. The CDC notes that there are “risks including pain, bleeding, and infection, more serious complications are rare.” In a British Medical Journal article, Dr. Kirsten Patrick notes that the male circumcision carries a complication rate somewhere between 0.2 per cent and 3 per cent, and carries little risk if capably performed.

Though there are studies to cite on both sides of the argument about male circumcision, as highlighted in this by Patrick and Hinchley, I believe that there is no room for debate about FGM, which is misogynistic and morally wrong.

MGM is about controlling male sexuality as well – quoth Harvey Kellogg, Rabbi Moses Maimonides and Isaac ben Yediah. And it serves to entrench male dominance over women by making them less sensitive – less ‘female.’ It is such a male status symbol that men in some areas have been physically accosted and forced to undergo it. The anatomy is different but the causes, reasoning and ethics are identical – and MGM will always be used as an excuse to promote FGM. Anything patriarchy forces on anyone’s body is about either harming women or making better rapists out of men.

The argument from severity also allows less severe forms of FGM to go unnoticed and unprosecuted – nearly half of it happens outside Africa but is ignored because it’s not as severe. The disease arguments are a red herring – penile cancer is twice as rare as vulvar cancer and the HIV studies were done on very small sample sizes by groups seeking funding. In US studies it made no difference to HIV rates. Anyone can invent surgical alterations that have minor beneficial effects (appendix? tonsils? skin bleaching as a response to racism? microchip implants to keep kids ‘safe?’) – those effects are irrelevant until the owner of the body consents. Unless the right to bodily integrity is upheld for girls, boys and intersex alike, no one is safe. Arguments that MGM can be beneficial inevitably lead to unsanitary circumcisions in many countries, a belief that circumcision totally stops HIV, and to the belief that FGM can have similar benefits if done ‘properly’ in a hospital. Studies have shown that some FGM is beneficial, and some survivors say it didn’t affect their sexual response. The only defense against such lies is a blanket condemnation against all genital cutting and other forced cosmetic alterations. The right to bodily integrity is universal, and it preempts any argument for FGM, MGM, breast ironing, foot binding, and other horrors yet to be devised. Half measures are self-defeating . And the reason I fight FGM is because my being cut as a male requires me to take all such violations personally (whether more or less severe – rights are equal even when violations are not). People do not act otherwise.

” Another argument has equated female cutting with male circumcision. This is fundamentally wrong, as male circumcision has little or no negative impact on the sexuality or future health of the male.”

Fact check time: This is utterly false. Sorrells et al showed in 2006 that the male prepuce, amputated during circumcision, includes the 5 most sensitive parts of the male sex organ.

Frisch et al showed in 2011 that circumcised men and their partners are 3X as likely to suffer frequent organ difficulties.

Dozens of boys die from their circumcision wounds every year in South Africa alone, dozens more have their genitals amputated after infections.

You have NO CLUE what you are writing about!

That should say “frequent orgasm difficulties”