The Sochi Olympics were the most expensive Olympic Games in history and, by some estimates, more expensive than all other Winter Olympics combined. This price tag presents a question: what were the Russians trying to buy?

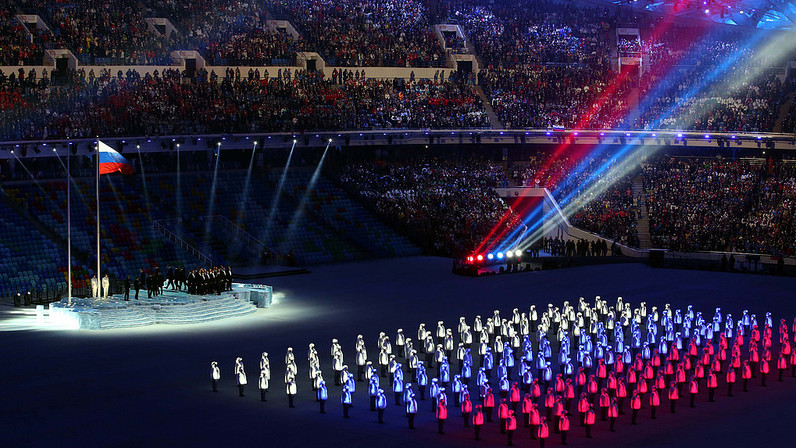

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s intentions had been clear since Sochi’s selection in 2008: “At last Russia has returned to the world arena as a strong state — a country that others heed and that can stand up for itself.” However, with disgruntled journalists live-tweeting their experiences in Sochi’s troubled hotels, a heightened terror-alert and political activist Alexei Navalny launching a website to expose corruption in Sochi, the big posters in Sochi proclaiming “Russia — Great, New, Open!” seem increasingly misplaced. Putin’s wish to showcase Russia’s strength was marred by negative international media coverage on everything from gay rights to guest workers’ pay. The country’s weaknesses – corrupt institutions and human rights abuses – rather than its strengths took the spotlight. What kind of Russia was the Kremlin attempting to portray, and who was the intended audience for this display of extravagance? While international coverage of the Olympics challenged Putin’s attempt to show off to the rest of the world, it is possible that Putin’s aims changed over time, and that international media underestimated the domestic importance of the Olympics. The Russian bid for the Olympics was presented in 2006, not long after a bloody victory over a drawn-out Chechen rebellion. In deciding to host the Olympics in Sochi, Putin directed the world’s attention toward the Caucasus region, a historically violent place. The decision was a gamble, indicative of either hubris or calculated risk. Hosting the games in Sochi was a clear nod to the domestic Russian audience. Considering the added risk of arranging the Olympics in an area known for centuries-long bloody conflict and recent terror attacks, it is clear that the Games’ location seemed to offer a political reward.

Putin’s popularity was partly based on his success in ending the war in Chechnya, which (like many other things) had been severely mismanaged by the Yeltsin administration. In fact, Chechnya had briefly been allowed full autonomy, virtually seceding from the Russian Federation. This autonomy was quickly removed after a series of terrorist strikes in Moscow and other cities. International journalist Christian Caryl opines that Putin effectively rehabilitated the war-weary region by first destroying and then rebuilding Grozny, the capital of Chechnya. Others, like Gregory Shvedov, editor of the news site the Caucasian Knot, believes that the “rehabilitating” nature of Putin’s stimulus money in the Caucasus has been largely propagandistic. In a way, Sochi is the site where the new and strong Russian state will finally prevail – or ultimately fail to. Keeping this in mind, the extreme safety measures taken by the Russian government seem amply justified. According to the Caucasian Knot, the death toll in the region was close to 1,000, in addition to those deaths caused by the three terror attacks in Volgograd. In Shvedov’s view, “the ‘bloody events of the Caucasus’ are not [only a] reality of the nineties, they are real today.” Some international observers pointed out that the seemingly secure Sochi was at serious risk. The “ring of iron” around the event had serious vulnerabilities, and it was up for debate whether the 70,000+ Russian security forces imported for the event would be able to handle the security pressures. On one hand, rebuilding and rehabilitating the public image of the Caucasus was clearly one of the main domestic motivators behind Russia’s original bid for the Olympics. As Putin put it in a recent interview, “There is also a certain moral aspect here and there is no need to be ashamed of it. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, after the dark and, let us be honest, bloody events in the Caucasus, the society had a negative and pessimistic attitude.” However, the gamble could have backfired; security threats were very real.

On the other hand, the motivation for organizing the Olympics was also clearly of an international nature. After all, what are the Olympics if not a way to show off to the world? The seventeen-day-long competition drew huge international TV audiences. The Russian state news agency RIA Novosti published an opinion piece that warned not to write the political legacy of the Games before they took place. According to them, “as with London, many of the political issues tend to fade when the sporting action starts. Sochi organizers can only hope that… the post-Games narrative is dictated by the oohs and ahs from the snow and ice.” However, international perception is unlikely to change given the consistent onslaught of negative PR since Russia’s anti-LGBT law was signed last June.

If the point of the Olympics was to show off Russia to the world, Putin has done little to mitigate the negative media attention Sochi has gotten. If anything, the way Putin has handled press disaster after press disaster has been indicative of the opposite – he does not care how the foreign media interprets him. For instance, in response to Olympic Committee member Gian-Franco Kasper’s statement that “up to a third of Sochi’s circa $50 billion budget had possibly been siphoned off,” Putin said, “I do not see serious corruption instances for the moment, but there is a problem with overestimation of construction volumes.” According to Putin, the overestimation of construction volumes took place during the bidding wars preceding the Olympics. When forced to reconcile Russia’s anti-gay legislation with gay Olympians, he stated that they would be welcome in Sochi, as long as they “leave the children in peace.” These clumsy and unapologetic answers leave much to be desired and have done nothing to improve Russia’s international image.

Russians themselves are divided on what they think the motivation for hosting the Olympic games were. However, in a new poll released February 5 by RIA Novosti, 38% of Russians believed “opportunity for graft” was the most likely motivation for authorities’ interest in hosting the Olympics. Twenty-three percent said the Games were meant to boost sports and unite the nation, and 17% said they improved the government’s public image. It is interesting that a combined 40% believe the “official explanation,” whereas almost the same number, 38%, believe that corruption is the main motivator.

It is clear that Russia’s initial motivation was to flex its muscles both domestically and internationally. In a way, the Games fit right into previous displays of power that have taken place in the Caucasus, though these displays have usually been of a military nature. The problem with the Western media’s commentary is that it has overestimated the importance of Russia’s international aims, likely a remnant of Cold War thinking.