There’s a general understanding amongst the members of the American public that midterm elections are not, for most presidents, terribly pleasant. Much like the reevaluation that sometimes follows a daring decision to consume dodgy oysters, the American public reconsiders the rumblings in its stomach and is gripped by a putrid sense of buyer’s remorse. As a result the midterms are commonly perceived to be a cyclical referendum on our leaders’ performance, but that view suggests that the party in the presidency can make midterm gains if they have governed well. Past history suggests a much harsher trend.

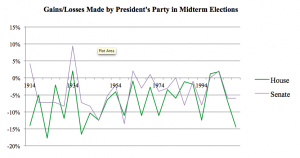

In the one hundred years since we settled on a 435-person House of Representatives and popularly elected Senate, our country has had twenty-five midterm elections. The president’s party has made advances in the Senate in a mere five of those 25 elections, and in the House of Representatives, a paltry three of 25.

The President’s party loses, on average, just over 31 House seats each midterm election, with the highest loss at 77 (a number that may go a long way towards explaining Warren Harding’s heart attack). The Senate is a little more merciful, as the incumbent party loses just fewer than four seats on average every midterm election; the worst performance in this chamber belonged to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who lost 13 Senate seats during his final set of midterms. When viewed proportionately, this comes out to mean losses of 7.4 percent and 3.8 percent in the House and Senate, respectively.

But these numbers are only partially representative of the electorate’s preference for kicking out the president’s party. Only a third of senators face their constituents each midterm cycle. If the numbers are calculated to illustrate the portion of seats won by each party, the president’s party fares worse in the Senate: party members win 38 percent of available Senate seats and 42.9 percent of such seats in the House. It’s not hard to uncover the mystery behind this difference. Senators in general enjoy lower rates of reelection, possibly due to the lessened intimacy between senators and their constituents — a natural byproduct of the fact that most senators are tasked with representing far larger and more diverse groups of citizens than most House members are.

It is very clear from these statistics that this fall, the president’s party is likely to have a difficult set of elections. What pundits and statisticians alike cannot decide on is how bad it will be. While stories of Bush II’s fortunate first midterm and the other ghosts of midterms past can spice up the coverage of otherwise dull races, too much of this sort of analysis masks the underlying trends. “Lame duck” midterms (the second midterm of a two-term incumbent) aren’t really worse for the president’s party than midterms during a president’s first term. They’re just different. If fact, the two are almost mirror images:

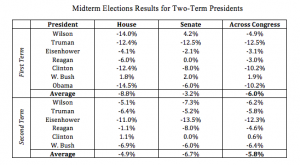

The table above outlines the net changes in the House and Senate for every President who has experienced two midterms in a two-term presidency in the past one hundred years. Recall that average changes overall are -7.1 percent in the House and -3.8 percent in the Senate. As such, we can see that the first term observes a shellacking in the House, but not-as-bad-as-usual results in the Senate. Au contraire, second-term presidents do comparatively well in the House, while suffering miserably in the Senate.

So far, so foggy. But how do individual presidents do? Eisenhower and Bush II did considerably worse in their second terms, Clinton and Truman did noticeably better, and Reagan and Wilson did terribly in one chamber and excellently in the other. Eisenhower is the most obvious example of the “lame duck” midterm myth, and for good reason — losing 13 seats in the Senate and 48 in the House makes his story an excellent example of the doomsday midterm scenario. But Eisenhower is the exception, not the rule. When you average seat changes across both chambers, the second-term president usually does marginally better. President Obama’s lame-duck midterm could yet affect the finely balanced record, however.

This close analysis of the numbers is all very well and good, but it still begs the question of just what the American electorate could be up to — after all, why elect someone to carry out a political agenda, doctrine or platform only to purée their political party and thus their chances of enacting that platform at the next opportunity. At best, it’s hopelessly inefficient. At worst, it’s downright masochistic.

The natural refrain is to think that American voters might just bear a deep and bottomless grudge for the presidential office (a truism that holds at the very least among Fox News watchers). But, in a voter-psychology sense, it’s entirely reasonable to suspect that the most preeminent and public face of the nation bears the brunt of responsibility for the country’s various ills: recession, war, the decadence of social programs. You name it — it’s the President’s fault, or at the very least the party whose flag he bears. It’s intuitive and, surprisingly, isn’t entirely unfair. The raw, etymological meaning of the word “President” itself evokes responsibility, even in the absence of fault. The president might not have made the mess, but it’s his (or hers) to clean up. On the other hand, the view of presidents as omnipotent country-custodians may give far too much credit to the role; many aspects of a country’s state, like the economy, social problems or your neighbor’s habit of playing Norwegian speed metal in the middle of the night are simply beyond the capabilities of the office to fix single-handedly.

As it turns out, social psychology may offer some more solid answers about sentiments surrounding the Leader of the Free World. Robert Cialdini, author of one of the field’s most preeminent works, writes about the power of associations, chief amongst which are the emotions we attach to the bearers of tidings, good and bad. Cialdini’s prime example of this is the varied plight and joy of a weatherperson — in short, whether people like them or not is intrinsically linked to the quality of the weather that they report, which, of course, has nothing to do with them as individuals. As such, weather people are showered with love or disdain depending on which part of the United States they find themselves employed in (as you can imagine, weather people are in high demand in Minnesota). It’s tempting to think that, just maybe, the same is true of presidents.

Yet, time and time again, the American electorate has left its stormy sentiment and ill-will towards the incumbent behind and invited him back into the White House. A mere five of the last 18 incumbents have been defeated when running for reelection to the Oval Office (Bush I, Carter, Ford, Hoover, and Taft). You’ll recall the crude food poisoning metaphor in the first paragraph: the dish that was once a source of regret may become a delicacy once the gastronomic seism becomes a distant memory.

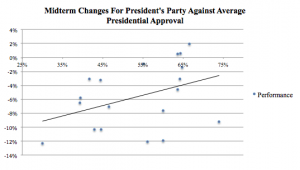

Moreover, although there is a positive correlation between a president’s average approval rating in the months prior to the election and the performance of the president’s party across the chambers of Congress, it is not at all a strong one.

Presidents with marginally different average approval ratings have suffered or enjoyed vastly different midterm outcomes. In short, though it’s a tempting hypothesis, the presidential weatherman theory has to be dismissed, as perceptions of the president don’t seem to have an especially powerful effect on election results.

If personal rancor towards the president isn’t the answer, perhaps displeasure towards government in general is the fuel that keeps the incumbent-roast going. In essence, this view would have midterms attract a disproportionately high number of protest votes. Not as much is at stake as during a presidential election, and as such, sentiment turns more generally against the establishment than for or against a particular candidate. This model would fall into line with those in the rest of the world, where there are numerous examples of the nonexecutive election being used to protest. In Europe, political scientists from the University of Mannheim have analyzed trends in European Parliament elections, with intriguing results. It’s difficult to make exact comparisons to midterm elections in the United States, for the vast majority of European countries follow a parliamentarian model, in which the executive is made up from members of the legislature, and as such are elected at the same time and in the same way. Even so, the findings can be enlightening. Europe’s executive-incumbent parties — effectively, the ‘party in charge,’ or host of the political process for the evening — perform similarly badly in nonexecutive elections as parties in the United States.

Sebastian Popa and Hermann Schmitt, the academics in question, also noted that in European Parliament (EP) elections, turnout is lower; the same is true for midterm election turnouts in the United States compared to their general election big brothers. And turnout, unsurprisingly, is a fairly good marker of the importance voters attach to a certain election — if it’s not important, they simply won’t wait in line. When an election is deemed less important, because it is perceived to have less impact on a voter’s welfare, votes as an expression of discontent are more likely — a voter can easily and symbolically express their general discontent with the government with minimal fear of repercussions, since the vote, and the election, isn’t perceived to have a strong real impact. Consequently, midterm elections come across as the perfect opportunity to express dismay at the government, primarily directed towards the party who controls the White House. This phenomenon is able to occur with unique strength in the United States because we have a strong two-party system; unhappiness with one party can easily translate into support for the other, whereas in a multi-party parliamentary system, discontent is much more difficult to express.

There are many ingrained reasons for the existence of the two party system, but one element of its perseverance — voter psychology — may hint at another reason why voters are quick to change their mind about the president and his bedfellows. It may be that the reflexive rejection of the incumbent presidential party is a monolithic and subconscious way of maintaining political balance. After all, polls indicate that, partisan considerations aside, Americans tend not to want the same party to have control over the two elected branches of government, so it’s not entirely out of the question to presume that this attitude favoring divided government hasn’t changed an enormous amount over time. Midterms may then simply be the other end of the electoral seesaw — a peculiarly and particularly American method of ensuring that government does not lean too boldly in any one direction.

The picture drawn by this theory isn’t a clear one, but it’s possible to make out a few distinct trends. That aforementioned fondness for divided government, which manifests mostly among independents and mid-aisle partisans in the US, provides a motive for the regular rejection of the president’s party come midterm season. But, a look at history books provides evidence that is initially discouraging for our hypothesis; the long-term fortunes of both major parties in Congress yields a 44-year Democratic majority in the House. With this in mind, the seesaw argument for discontent looks like a tough sell — that’s 22 election years and 11 midterm years in which the Democrats held onto the supposedly more volatile chamber of Congress. In the 50 Congresses since and including 1914, 27 have observed party unity across the House, Senate and White House. Case closed? Not quite. Perhaps the most compelling complication is the influence of Southern Democrats, who tended towards fiscal conservatism and were against civil rights reform for much of the mid-twentieth century — positions that put them at odds with the rest of the Democratic Party. This split meant that while the Democrats had a majority in name, it was not a majority in practice, as Southern Democrats and Republicans frequently collaborated. On a more quantitative level, since and including 1914 the average proportion of Congress that belongs to the president’s party after a midterm election is 50.5 percent: a few tenths of a percentage point off a perfectly balanced Congress (for the record, the median is 48.9 percent). As such, on average, the congressional aftermath of a midterm election is extremely close to perfectly balanced. If American politics is a circus, then midterms are the tightrope walker.

Midterms are nasty for presidents. If anything is clear, it’s that. The raft of bludgeonings that presidents’ parties have experienced through the years attests to that and completely and utterly redefines midterm electoral success: not making gains, but cutting losses. Although personal popularity does help alleviate the stress of midterms for presidents, it only goes so far, and it hardly guarantees results. The second midterm of a two-term president is as likely to be a lame duck as the finale to the tale of the ugly duckling. In short, there’s no distinguishable pattern. The sources of midterm madness are manifold and deeply complex. A reflex reaction against an incumbent president is most likely not the answer, but the protest vote and righting of the political ship theories are certainly factors.

If there’s one thing to take away on the subject of midterms, it’s this: The 2014 version is unlikely to be kind to President Obama. The New York Times’ latest prediction expects the Republicans to gain six seats in the Senate, and it appears to be on the right side of history in this sense. Regardless, if midterms down the years are a fable that narrates how the electoral reach of presidents is greater than their grasp, President Obama can expect yet another instance in which the American electorate bites the hand that leads.