Magdaleno Rose-Ávila, a revered hero in many Latino communities, former CNN hero of the year and a tireless civil-rights activist, was once a gang member. His experiences in and eventual disengagement with gangs galvanized a desire to expand opportunities for young gang members, outside the pressures of organized crime. This precipitated his founding of Homies Unidos in 1996 as “a group committed to gang prevention via youth empowerment,” which remains one of El Salvador’s most discussed NGOs today. Two years after the organization’s original founding, it opened an office in L.A. Due to significantly greater funding and external socio-economic conditions conducive to growth of civil society, the North American branch has since achieved effective results in the community. Meanwhile, the original branch has fallen behind, having been ostensibly shut down during the late 1990s by the Salvadoran government. Homies Unidos (El Salvador) prides itself on an incredibly intimate connection with youth gang members and their powerful bosses. So intimate, that a nebulous gray area has risen. It is this anomalous relationship, and it’s development over the years into an arguably pro-gang disposition, that lies at the crux of the organization’s largely ineffective policy and subsequently adverse effects in the community. Moreover, an analysis of Homies Unidos within El Salvador’s broader socio-political context highlights just how far the country is from establishing an effective civil society.

So, where did it go wrong? How can an NGO with pure intentions, close community ties and a theoretically revolutionary action plan have had an adverse effect on the people it sought to help? The answer lies in the question. The relations with gang members became so inextricable, and so bent on getting the youth gang members and their affiliates to identify with the organization on a trustworthy, peer-to-peer level (hence the name, “Homie”), that it perpetuates the already predominant “gang culture”. The staff of Homies Unidos self-identify as pandilleros calmados, a label signifying that they have distanced themselves from the drugs and violence aspect of gangs, but continue to partake in the gang lifestyle for the sake of friendship and camaraderie. Sonja Wolf, a scholar and expert on civil society in El Salvador, describes the implications of this position, saying, “The difference between pandilleros calmados and ex-gang members (who have severed all ties to the group) may be immaterial if the former stop participating in crime and violence. Insofar as gang work is concerned, however, scholars have suggested that ex-gang affiliates are unsuited for such tasks, because they tend to over-identify with gang values and norms and risk showing pro-gang/anti-police attitudes that may increase gang cohesion and delinquency.”

It is this effort to establish a “Homie”-esque relationship with their clients that has entrenched the organization in the depths of organized crime. Thus, Homies is promoting the participation in gang life to their advisee’s, rather than facilitating the severing of ties. Being waist-deep in the orders of gangs has perpetuated the organizations’ characteristic advocacy strategies. Wolf, upon living in the communities and working with Homies Unidos throughout her dissertation process, poignantly described the insidious culture of corruption within the organization, saying, “My existing uncertainty about [Homies Unidos]’s staff and their motives intensified, understandably perhaps, with the co-director’s detention…I had the suspicion (which was later confirmed) that staff were fabricating his alibi to secure his acquittal.”This malfeasance is not only a propagation of the very issues the organization ostensibly seeks to address (gang affiliation, organized crime), but is also inhibiting any effective advocacy work. The corruption tarnishes the political capital needed to effectively serve the youth in gangs, as well as the funding needed to maintain a non-profit. In an effort to mitigate the omnipresence of gangs, the conservative Salvadoran government of the early 21st century initiated Mano Dura policies, infamously described as being “zero-tolerance policing strategies.” Central America’s equivalent of the ‘Iron Fist,’ these strategies targeted gangs antagonistically and reactively, which included the immediate imprisonment of a gang member, simply for having gang-related tattoos.

Mano Dura policies are objectively against any and all cooperation with gangs themselves, and Homies Unidos’ affiliation with gangs inherently contradicts that. “It suffices to note,” remarks Wolf, “that Homies Unidos continued identification with gang culture limited their policy influence, because it informed their strategic choices and shaped external perceptions of the organization, thus restricting relationships with other actors.” While, Homies Unidos does provide an incredibly supportive space for immigrants who have recently been deported back to El Salvador as well as for youth struggling to separate themselves from gang life, its severe inability to mobilize effective advocacy strategy limits its overall impact to simply being a supportive environment.

The organization must therefore grapple with compounding variables: They are unable to gain any political ground for the sake of youth in gangs and are also exempt from receiving any government funding, which is intrinsic to the function of a non-profit. This has forced them to revert to “stop-gap measures to keep the organization afloat.”

A vicious cycle reemphasizes the NGO’s ineffective strategy: affiliation with gangs inhibits adequate funding, which then forces them to revert to corruption within the parameters of organized crime, thus pushing the organization back into the depths of the “gang society.” This further promotes “project-based” humanitarianism, where sporadic and reactive policies do not address the core of the problems, mainly because they do not have the funds or professionalism to mitigate the core of the issues they seek to address. “In recent years,” writes Wolf, “Salvadoran NGOs have tended to maintain a largely reactive attitude to the country’s problems and have shown little capacity either to propose alternatives to existing measures or to influence public opinion.”

Homies Unidos’ unprofessionalism and incestuous gang affiliations, confounded by the subsequent lack of government funding, highlights the true pitfalls of Salvadoran civil society. Michael W. Foley explains in his essay, Laying the Groundwork: The Struggle for Civil Society in El Salvador, that, “The [Salvadoran] government continues to direct its resources, almost overwhelmingly, to inefficient and, at times, corrupt government agencies, ARENA party mayors, and the ‘private sector’ NGO’s.” US interests and desire for a business-oriented, “private sector” heavily influenced the government’s creation of a post-war civil society. This excludes groups like Homies Unidos from receiving funding, who despite having devolved into corrupt strategies, maintain an altruistic mission statement incongruent with that of the government.

In this vicious cycle of corruption, malfeasant strategy, and criminality, NGOs such as Homies Unidos eventually inflict adverse effects on the communities it allegedly serves. But Homies Unidos is prevented from breaking the cycle because it is considered undeserving by a self-promoting government that refuses to fund organizations that do not fit within the narrow parameters of their business interests. As a result, the El Salvadorian government fails to support the development of a “public” civil society. Until something changes, El Salvador’s struggling non-profit sphere is stuck between a rock and a hard place, at the intersection of confounding variables. Until the culture of corruption is mitigated on both sides, civil society in El Salvador will remain a struggling enterprise.

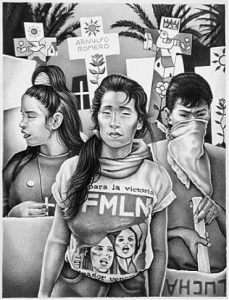

And a SLIGHT correction may be warranted with regard to the caption– (probably fault of the editors): “Artist Mark Vallen depicts the poignancy of the Salvadoran struggle for equality and peace. The countries’ disparate civil society inhibits such movements from gaining much political ground.” In fact, the FMLN (former guerrillas who formed a political party in 1992) has been in power 6 years; it’s now in its second presidential administration.

Co-opting by gangs of well-meaning NGOs and individuals happens in El Salvador in part due to the dynamics this article describes, and it continues to happen (check out recent reporting on the jailed priest Antonio Rodriguez). But Ms. Perez’s reporting is very dated and is missing a lot; she is clearly not following El Salvador closely or carefully. For one, ARENA has been out of national power 6 years, and its mano dura policies are a thing of the past. Neither is there any mention of the controversial 2012 gang truce, the biggest development in the gang-gov’t-NGO-nexus (and a big mess). I would suggest that if she were to continue writing about El Salvador and about gangs especially she consult some of the very accomplished journalists here who can lay this all out for her very precisely (El Faro editor Carlos Dada, eg.). Relying on old work by American academics won’t suffice.

Informative, interesting, and intelligently written.