It’s a well-worn cliché that older generations complain about their descendants’ privileges, but that doesn’t mean that it is any less justified. Parents seem to take a special joy in reminding their children that when they were learning calculus, they didn’t have the luxury of graphing calculators or fancy computer programs. Their complaints are especially pronounced in regards to academic research; often complaining of long nights at a physical library, sifting through disorganized card catalogs to find old books. The Internet has rendered such drudgery obsolete, placing a vast portion of the world’s knowledge only a few clicks away. While parents’ diatribes grow tiresome, they do reflect an important point: The Internet has already revolutionized the way we learn and has the potential to upend a system that has more or less remained static since the beginning of public school education in America.

The American public school system isn’t much different from when it was started. While we’ve moved away from the one-room schoolhouse, most lessons are still delivered in a simple lecture format and students complete homework at home. The school year itself, among the shortest in the world, is a relic from the country’s agrarian past. It is a system long due for an overhaul, and advances in education are especially important right now given the general consensus on the dismal state of schools in the United States. A 2012 ranking by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) judged US students to be below average in mathematics, ranking 27th in the world and barely on par with other developed nations in reading and science.

The Internet offers tantalizing possibilities to revolutionize the educational system, especially since 87 percent of the country’s population is active on the Internet. One of the most common innovations — moving the classroom online — has the potential to transform American schools. Proponents contend that its adoption will make for a more egalitarian system where students’ choices are not limited by geographic location or poverty. The explosive growth of massive online open courses (MOOCs) reflects this thinking as does the great increase in opportunities for distance learning. In 2010, 55 percent of public school districts offered online courses. The proportion has only grown since. The College Board lists over 500 online providers for AP courses, and in 2010 the International Baccalaureate began developing its own online platform.

The Internet has already revolutionized the way we learn and has the potential to upend a system that has more or less remained static since the beginning of public school education in the United States. Online classes for K-12 students, proponents contend, will improve the system by offering students more choice and access. In Iowa for example, where 98 percent of schools are rural, online courses allow rural students access to the same courses enjoyed by their urban counterparts. Internet-based innovations also take on other forms. One is the flipped classroom, where students watch lectures online at home and then work on class problems during the school day with teachers available to help. Khan Academy has attracted more than 10 million users, and the company is working with schools to develop a sort of hybrid classroom, with some of the learning conducted through online instruction and some through more typical methods. It’s too soon and still too uncommonly used to be able to gauge the method’s effectiveness just yet, but teachers contend that students complete the work faster and that the technique is more accommodating of individual learning styles and speeds.

However, the increased use of online learning in K-12 education is not without its flaws. Even though the Internet appears universal, in many parts of the country that isn’t quite the case. The federal government estimates that less than 30 percent of K-12 schools nationwide have adequate broadband Internet. The cost of updating and improving technology may be prohibitive, especially in the rural areas where improvements are needed the most. That means that while some areas of the country are able to harness new educational opportunities online, a great portion of the nation is not — hindering the ability of virtual classrooms to transform American schools. Additionally, there is evidence to suggest that the expansion in online education comes at the expense of traditional classrooms and teachers because politicians will be able to point to an expansion in online opportunities to justify cutbacks in physical classrooms. It also isn’t clear how effective the courses are; no peer-reviewed rigorous studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of online K-12 classes, although College Board and a plethora of more informal studies state that scores for students from online courses match those achieved by those in traditional classrooms. While there are clearly some limitations with online courses, they should not be case aside and are still a potent tool for improving education outcomes at least in K-12 schools.

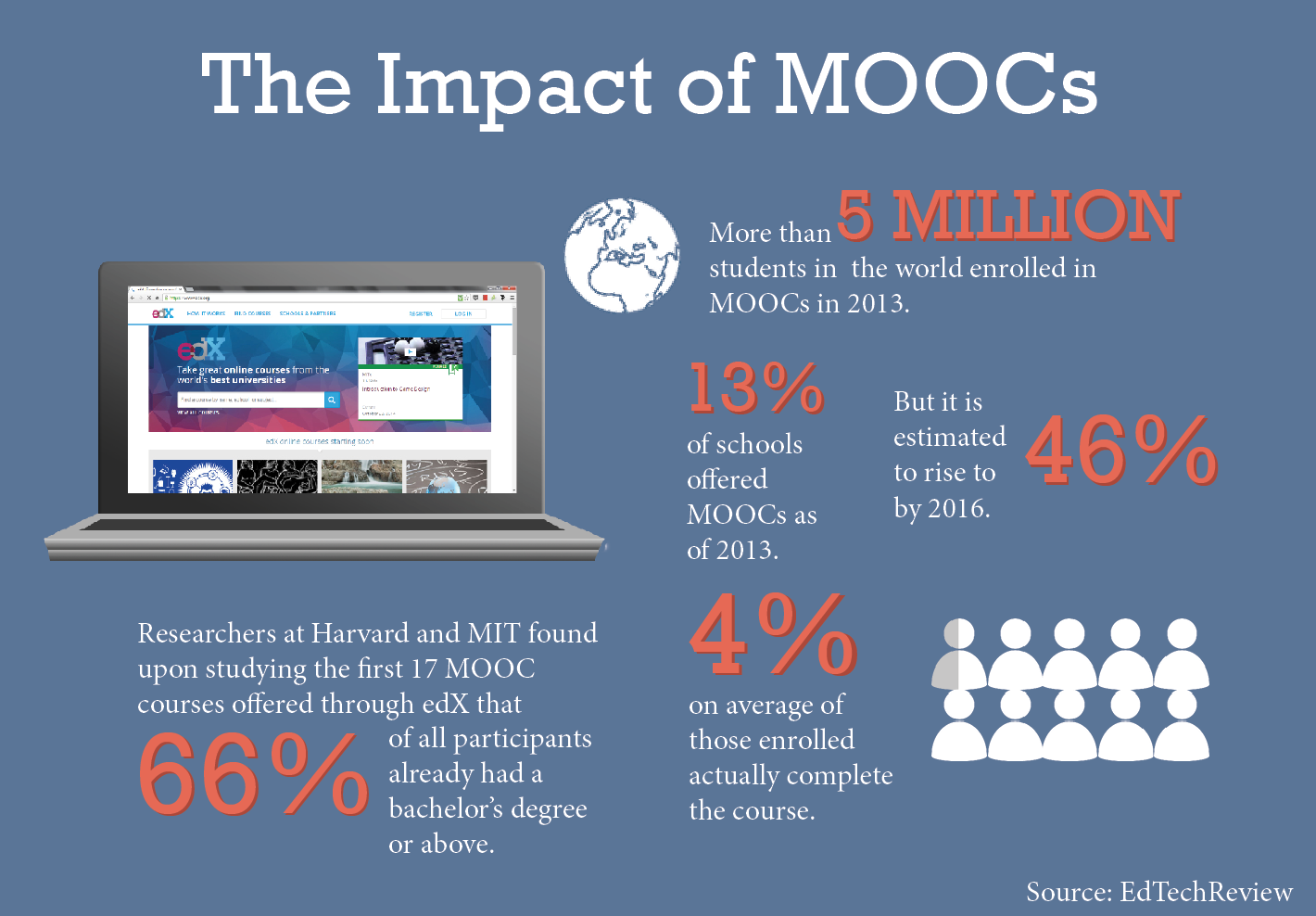

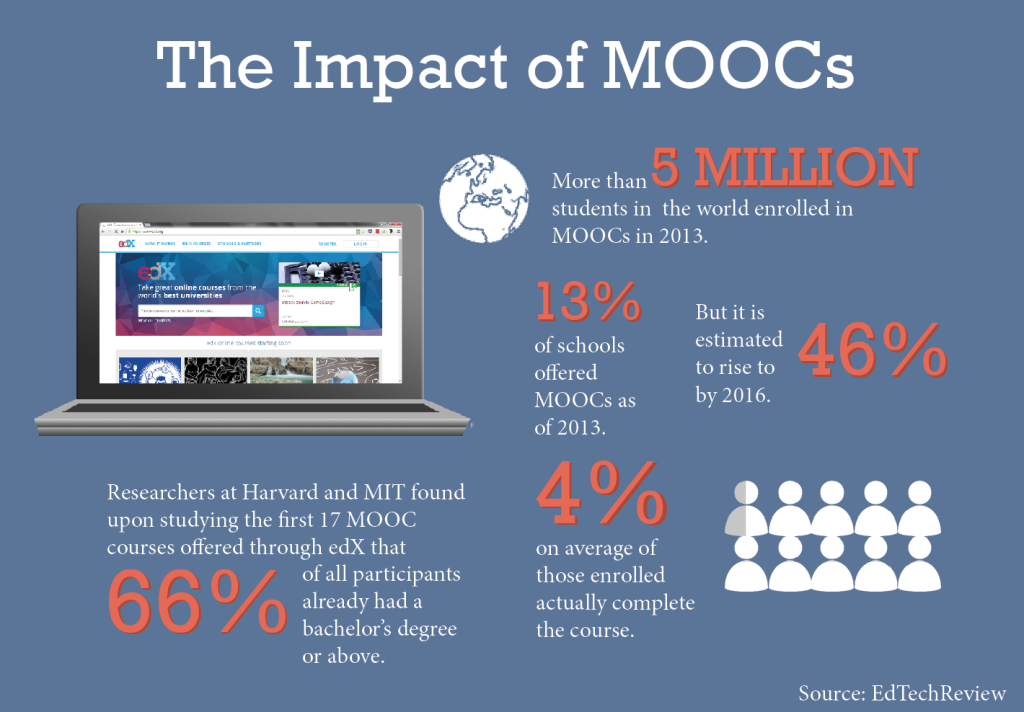

The picture is different when it comes to higher education. One of the most publicized recent developments has been the massive online open course, or MOOC. MOOCs offer the tantalizing possibility of a college-quality education for anyone. Most importantly, they’re free, an especially attractive feature given the 12-fold increase in the cost of a degree.

The growth in MOOCs is breathtaking. Coursera, a platform for the courses, was founded in January 2012 and by November of that year boasted 1.7 million users. It is part of a long list of similar ventures including edX, Udacity and Class2Go. Although the playing field is diverse, the companies all have the same hope — that free courses can bring an elite education to all corners of the planet, democratize education and create opportunity for upward mobility. These platforms cast themselves as the future of higher education, a potent message giving the many problems faced by traditional colleges and universities. This rosy façade obscures some potential pitfalls, however.

Despite the fanfare, the MOOCs’ true benefits lag behind its supporters’ high hopes. Engagement drops steeply after the first few weeks, and only about 4 percent of those enrolled actually complete the course. A concern shared with K-12 online courses is that MOOCs will be seen as a replacement for flesh-and-blood instructors. Furthermore, the huge size of the courses makes for an impersonal learning experience. The low completion rates may also be a reflection of the lack of any real incentive to finish; currently the MOOCs only offer a certificate, no sort of degree or real qualification. An avid MOOC-taker can enroll and excel in many Harvard or MIT courses and still come away with nothing more than a stack of certificates. This is not to say that MOOCs are failures, they just face challenges heading into the future. But they are beginning to adapt and address these concerns. Georgia Tech, for example, has developed an online master’s program in computer science that, if completed, will leave students with a degree, the sort of qualification many MOOCs currently lack. Although with a $6,000 price tag the program certainly isn’t free, it’s still far more affordable than the equivalent program on campus. The success of the initiative will help determine if MOOCs can really live up to their potential.

Newspaper headlines proclaiming the death of a traditional education in favor of an online equivalent are, at least at this point, a bit premature. The virtual classroom, however, has potential as it allows students across the country more equality of opportunity to enroll in advanced classes in diverse subject fields. Educational outcomes are still largely a function of the resources of the school districts and online courses may help level the playing field. Only time will tell whether or not the online classroom is something that will stay. But if it is able to facilitate access to education for at least some students it will be a success.