British politics are in a state of tumult. From the meteoric rise of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) to the unprecedented success of the Scottish National Party, the political landscape has undergone a transformation in recent years. Unfortunately, these shifts have failed to produce the structural changes that people had hoped for. The Liberal Democrats were debilitated by coalition politics; UKIP remains stymied by Britain’s nonproportional electoral system; and the Scottish nationalists didn’t quite pull off their referendum. The most recent beacon of populist hope is the ascension of Jeremy Corbyn to Labour Party leader. Yet even he seems to face impediments, with the parliamentary shadow cabinet and the annual party conference hard-wired against his success as leader. If Corbyn and his band of supporters — dubbed Corbynites — are to have any hope of achieving the reforms they seek, they must move quickly to change the internal mechanisms of their party, neutralizing the institutional obstacles before pressing onward with their varied policy objectives.

The election of Jeremy Corbyn, a veteran backbencher on the party’s left flank, as Labour leader is an incredible development in and of itself. Since 1983, the Labour Party has largely marched steadily rightward, concerning itself with purging the party of leftist figures and reshaping it in favor of more laissez-faire economics. Even the previous Labour leadership, itself perceived as left-leaning, towed a centrist line on issues such as welfare spending, the deficit, and immigration. So almost no one expected Corbyn, a figure associated with opposition to that centrist consensus, to succeed. That is until so-called “Corbynmania” took hold, electrifying stalwarts and newcomers alike. In the intraparty election for leader, Corbyn garnered nearly 60 percent of the vote in a field of four candidates — a slightly better showing than Tony Blair’s famous landslide in the 1994 leadership election.

Mr. Corbyn’s policy views, however, might pose a greater source of conflict than his supporters predicted. Despite Corbyn’s deep popularity with his supporters, much of the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) views their leader, both publicly and privately, with hostility. His republicanism, opposition to NATO membership, and pro-Palestinian and anti-Syrian intervention stances have not been well-received by most Labour parliamentarians. The grumbling grows even louder in response to Corbyn’s economic policies: renationalizing railroads and the postal system, halting the dramatic benefit cuts of recent years, adopting longer-term deficit elimination, and directing the Bank of England to embark on a capital investment program dubbed “People’s Quantitative Easing.” Though some of these policies poll quite well with the people of Britain, a great number of Labour Members of Parliament (MP) consider them both electorally unwise and somewhat outdated.

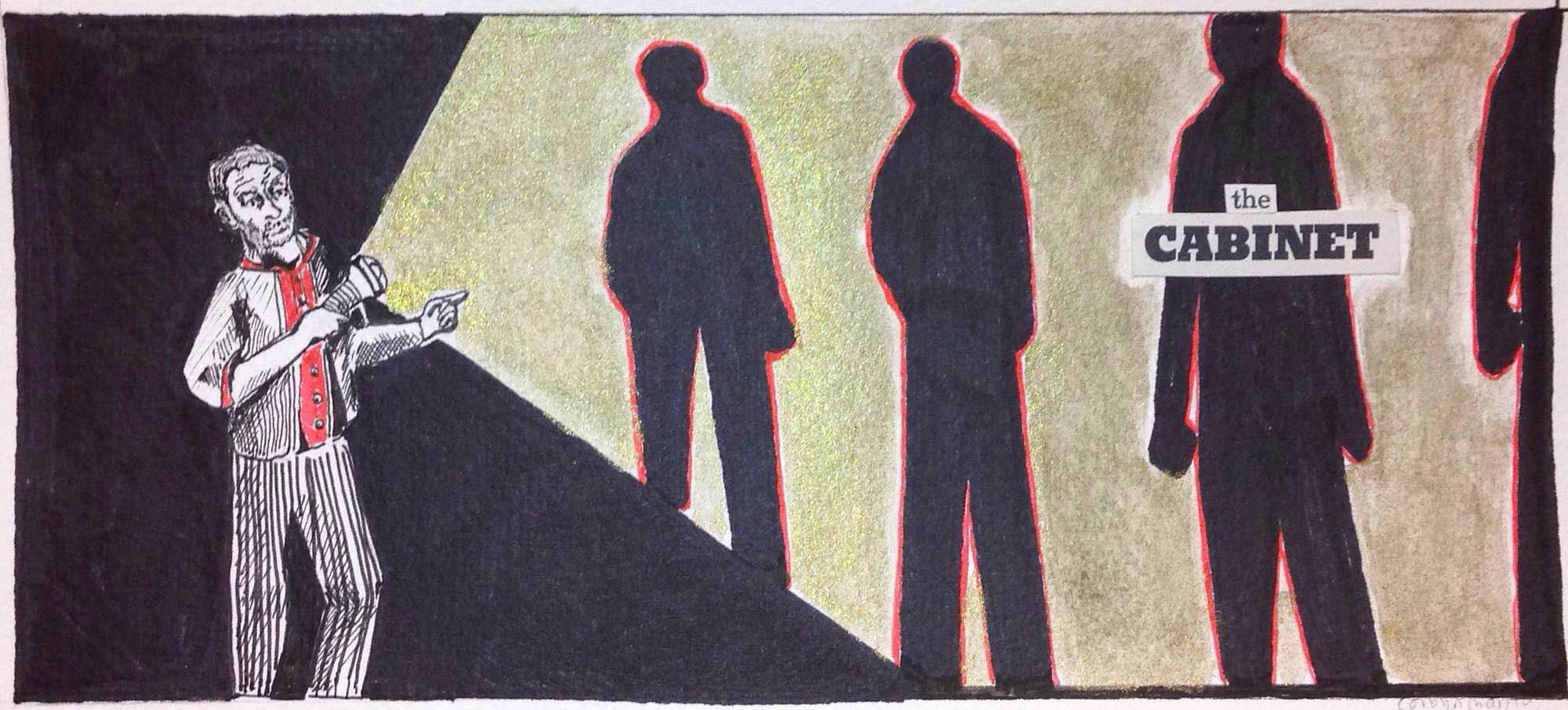

Corbyn’s crushing victory makes a direct PLP coup by his dissenters unlikely — for now. But the Labour parliamentarians can undermine the usurper without resorting to active sabotage. Their most powerful tool for disruption is called the shadow cabinet, which is ironically comprised of the very people who are supposed to have their leader’s back.

In British politics, the shadow cabinet represents the primary source of policy and leadership alternatives offered by the main opposition party. Appointed by the opposition leader, it functions largely as a mirror-image, albeit powerless, version of the governmental cabinet. Corbyn has appointed a shadow cabinet that draws heavily on more moderate Labour MPs, both for party reunification after a divisive leadership contest and out of an apparently sincere belief in inclusive decision-making. Outside of John McDonnell, the new shadow chancellor of the exchequer, a long-time Corbyn ally, the frontbench’s main figures are distinctly anti-Corbyn. Both Lord Falconer, shadow secretary of state for justice, and Hilary Benn, shadow foreign secretary, publicly supported one of Corbyn’s leadership opponents, Andy Burnham. Indeed, Burnham himself has a significant role as shadow home secretary — an especially notable choice given he and Corbyn stand apart on immigration policy, a key element of the home secretary’s policy portfolio.

This strange cabinet of grievances has already made trouble for Corbyn. Falconer fired the first salvo, saying he has “no idea” about Corbyn’s chances of winning the 2020 general election, as the right-leaning Telegraph gleefully reported. He further argued against Corbyn’s policies on ending the Trident nuclear program, apologizing as a party for the war in Iraq, and abolishing the welfare benefits cap imposed by the current Conservative government. Burnham has said that if the party officially adopts an anti-Trident policy, he will resign. Benn told the Independent that he would actively try to oppose Corbyn’s policies from within the shadow cabinet on issues such as Syrian airstrikes. Deputy Leader Tom Watson — who was elected by Labour members, not appointed by Corbyn — has also made critical comments on some of Corbyn’s policies. In short, Corbyn is almost as isolated within the shadow cabinet as he is within the PLP.

Such an unforgiving situation casts doubt on Corbyn’s appointments. Of course, Corbyn didn’t have many options to begin with; he doesn’t have many friends in Parliament, and several high-profile Labour MPs, including a few leadership candidates, refused to serve in the shadow cabinet. Additionally, if Corbyn had chosen a cabinet closely aligned with his own interests, he would have faced charges of heavy-handed radicalism and made open political rebellion more likely. In this way, the shadow cabinet represents a structural trap for Corbyn. No matter what he does, it’s easy for his parliamentary opponents to weaken him because the shadow cabinet is central to shaping policy and functions in the largely hostile House of Commons. The shadow cabinet’s structural importance makes an anti-Corbyn coup appear likely. Just ask the bookies, who are now giving him short odds of surviving as leader through 2020.

Corbyn’s way out of this trap could be to decrease the role of the shadow cabinet, and therefore the parliamentary party itself, in policymaking. Some Corbynites did in fact make noise about this, calling for an internal “democratization” of the party by largely sidelining the shadow cabinet or, at the very least, determining policy at party conferences. Tactically, this is a sensible move. Though the PLP is dominated by anti-Corbyn members, the grassroots Labour activists and members just voted for the Corbynite program by massive margins. If the power of this activist base were harnessed in policymaking, the tables would likely be turned.

The logical vehicle for a more democratic policy process is the party conference, a large meeting of members and activists held yearly by most parties. There is, in fact, precedent for using the conference as the ultimate source of policy. Liberal Democrats, for example, give much more policy power to their conference than either major party. And as the Lib Dems are ideologically homogenous for the most part, there isn’t all that much daylight between their members and the parliamentary party. That helps make the setup uncontroversial among Lib Dem MPs. Needless to say, the wide gulf between the populist and moderate wings of the party makes Labour a different beast, and a Corbynite attempt to push Labour toward this model would ignite serious opposition.

Corbyn seems to understand this. Unfortunately for him, the first party conference of his tenure was scheduled from September 27 to 30, almost immediately after his ascension to the leadership and too soon for a dramatic change in the conference’s proceedings. Corbyn did attempt to use this gathering to create mandates for some of his policies, which the PLP largely distrust, most notably by trying to schedule a conference vote on Trident. However, he wasn’t able to do so and left the conference in the same position he arrived in — shackled by his own shadow cabinet.

If the experiences of Corbyn’s young leadership show one thing, it’s that to succeed where other British political insurgents have failed — by turning electoral enthusiasm into meaningful policy change — he must first address structural issues within his own party. By embarking on a campaign of radical intraparty democratization and thereby harnessing the power of the rank-and-file party members in his corner, Corbyn can reduce the power of the politically divisive shadow cabinet. But time is of the essence. With influential party structures trying to depose him as quickly as possible, he simply can’t afford to wait for the next conference. He’s fighting an intraparty civil war, and as Napoleon said, “the logical end to defensive warfare is surrender.”

Art by Elodie Freymann