Though the civil war that shattered Côte d’Ivoire has been over for almost three years, the nation is still struggling to piece itself back together. Since taking hold of the presidency in 2011, after four months of crisis and bloodshed, Alassane Ouattara’s central mandate has been to unite the country and restore stability and prosperity. Thus far, his performance has at least yielded popular support. On October 25, 2015, Ouattara was reelected to a second term with over 83 percent of the vote and virtually no outbursts of violent protest. His closest opponent received only 9 percent of the vote. But even if the beginning of Ouattara’s second term shows how far Côte d’Ivoire has come since 2011, it also provides an opportunity to consider the many problems the country continues to face — from latent ethnic tensions and deep-seated national wounds to weak political engagement. The challenges Ouattara faces are not insurmountable, but to ensure that his legacy lives beyond the end of his term in 2020, he must address the underlying fissures that threaten to destabilize the nation.

Though the civil war that shattered Côte d’Ivoire has been over for almost three years, the nation is still struggling to piece itself back together. Since taking hold of the presidency in 2011, after four months of crisis and bloodshed, Alassane Ouattara’s central mandate has been to unite the country and restore stability and prosperity. Thus far, his performance has at least yielded popular support. On October 25, 2015, Ouattara was reelected to a second term with over 83 percent of the vote and virtually no outbursts of violent protest. His closest opponent received only 9 percent of the vote. But even if the beginning of Ouattara’s second term shows how far Côte d’Ivoire has come since 2011, it also provides an opportunity to consider the many problems the country continues to face — from latent ethnic tensions and deep-seated national wounds to weak political engagement. The challenges Ouattara faces are not insurmountable, but to ensure that his legacy lives beyond the end of his term in 2020, he must address the underlying fissures that threaten to destabilize the nation.

Côte d’Ivoire’s fraught history provides a crucial frame for Ouattara’s rise to power. Under the 33-year rule of President Felix Houphouët-Boigny, who led the nation after its liberation from France in 1961, Côte d’Ivoire experienced a steady influx of migrant workers into its northern region, the majority of whom were Muslim. During Houphouët-Boigny’s rule, a sharp divide emerged around the claim to Ivoirian national identity, or “Ivoirité.” Southerners redefined the term, which traditionally referred to a common Ivoirian culture and was inclusive of foreigners, to exclude Ivoirians from the north and west parts of the country. This xenophobic sentiment was eventually channeled into a law that prohibited anyone without two native-born parents from running for president — a move that stopped Ouattara, whose father was of Burkinabé descent, from seeking the position in 2000. The policy was indicative of the deep regional and ethnic resentment that sparked the country’s four-year-long civil war. After a peace deal was signed in 2007, then-President Laurent Gbagbo announced that Ouattara would be allowed to stand as a presidential candidate when the next elections were held in 2010.

When Gbagbo and Ouattara did finally face each other in the long-awaited election, the nation’s longstanding ensions were laid bare. Ouattara won with 54 percent of the popular vote, as counted by the country’s Independent Electoral Commission. The next day, however, the Constitutional Council — the body legally responsible for verifying electoral results — announced that many ballots from the north were invalid. As a result of the decision, Gbagbo claimed a narrow victory over Ouattara with 51 percent of the vote. This verdict was quickly rebuffed by the international community. Ultimately, both Gbagbo and Ouattara took the oath of office, selected prime ministers, and claimed to be the rightful leaders of Côte d’Ivoire. Eventually, on April 11, 2011, after four months of clashes between forces supporting each candidate, pro-Ouattara troops, with the help of the French, captured Gbagbo and handed im over to the International Criminal Court, where he still awaits prosecution. Although violence continued for a short time after his capture, April 11 marked the beginning of Ouattara’s tenure as president — and the beginning of his UN-backed mandate to unite Côte d’Ivoire.

Over the past four years, Ouattara has had some success. As a former International Monetary Fund economist, Ouattara made economic recovery one of his chief priorities. The presidential crisis had left Côte d’Ivoire’s economy reeling, with a 4.4 percent GDP contraction in 2011. Just three years later, GDP jumped 9 percent and is projected to continue growing at its torrid pace. This turnaround is largely attributable to increased national stability; with little widespread violence, Ivoirians could focus on the economy rather than fear for their safety. Another sweet surprise for the country’s economic prosperity has been an increased global demand for chocolate. As one of the world’s primary producers of cocoa, Côte d’Ivoire has been able to ride the wave of surging global prices.

Closer to home, Ouattara has implemented an agenda aimed at attracting foreign investment. According to the United States Chamber of Commerce, Côte d’Ivoire has encouraged business activity through “mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures, takeovers, and startups.” Beyond just driving growth, these policies are rapidly producing tangible benefits for Ivoirians: French companies have constructed light-rail systems, managed ports, and opened retail shops, and companies from China, Tunisia, South Korea, Turkey, and Kuwait have all invested or made plans to invest in infrastructure projects ranging from expanding ports to maintaining airports. These ventures are crucial to the Ivoirian economy, not only because they create jobs in the short term, but also because nfrastructure projects help create stable, long-term economic growth. Infrastructure projects will also allow the economy to diversify, which is particularly important given the Ivoirian economy’s dependence on luxury commodities like cocoa. Considering that sturdy and diversified economic growth is key to consolidating the strides the country has made in the last few years, such trends are highly encouraging.

Despite this rosy macroeconomic outlook, however, the demons of conflict still haunt the country. Although internal relations have been fairly peaceful since 2011, observers have noted that the absence of violence may be due to conflict fatigue rather than substantive progress in bridging ethnic and regional divides. While this creates the illusion of short-term stability, the failure to address deeply rooted divides leaves the country in a tenuous state of equilibrium. The fact that rebel groups are still armed, despite ceasefire deals signed with the government, only confirms this sense of structural fragility. These weapons may remain in warehouses for now, but if tensions reach a tipping point again, nongovernmental militias would have no trouble mobilizing for conflict. Further-more, Ouattara has been accused of preferentially selecting northerners for public service jobs. What has been called “ethnic readjustment” is seen as a tactic to help northerners economically; predictably, it stokes resentment in the minds of many southerners.

Ouattara’s failure to incorporate regional diversity in the government is the most visible failure of his tenure thus far. While it’s unsurprising that many of his top appointments would be close allies from the north, the civil service is brimming with northerners across the board. This disparity is problematic not only because it prevents a diversity of voices from being heard, but also because it hurts the government’s credibility. When southerners see only northerners in high-level national positions, they have little reason to trust the government.

Compounding this mistrust is the political monopoly held by Ouattara’s political party, the Rassemblement des Républicains (RDR). Although the RDR only holds 127 of the 253 seats in Côte d’Ivoire’s National Assembly, Laurent Gbagbo’s opposition party, the Front Populaire Ivoirien (FPI), holds none. Ouattara’s landslide victory in October also was marred by a tepid turnout, diluting the strength of his mandate. FPI supporters were split between boycotting the election in protest of Gbagbo’s arrest and supporting the official party candidate, who failed to garner more than 10 percent of the vote. Furthermore, the party best poised to provide the country with a healthy and robust opposition — the Parti Démocratique de la Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI), which holds 76 seats in the National Assembly — endorsed Ouattara in the election after their strongest potential candidate refused to run. With a pair of languid opposition parties and few Ivoirians deeply invested in the electoral process, the country is far from a vibrant democracy.

These myriad challenges pave a long road ahead for Ouattara. Barring further violence or unexpected turmoil, Ouattara will hit his term limit in 2020 and Ivoirians will select his successor in an open election. With many deep divides still present in the country, Ouattara must ensure that the fragile beginnings of stability and prosperity continue once he leaves. He must restructure his nation’s economic progress to benefit all Ivoirians, not just northerners. To fortify his nation’s democracy, he must also include citizens from all backgrounds in the civil service. He can begin by appointing southerners to key posts in his government and using them as examples for citizens of all political persuasions. Ethnic diversity at the lower levels of government is equally important, and Ouattara should work to begin a recruitment program targeted at underrepresented groups. Only through diverse civil involvement can Ouattara restore full faith and trust in the government and ensure its strength as a legitimate body going forward.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Ouattara must ensure that there is a competitive race for his successor. As it stands, none of the three major parties has a politician with enough national support to become a successful president. Ouattara can start by looking at his own party’s ranks and working to groom a successor. In a perfect world, Ouattara would also do something unthinkable for an average politician: attempt to restore the FPI and PDCI as legitimate opposition parties. If he chooses to do so, it will be no easy task — it may even include granting immunity to many FPI members who are still held as political prisoners. But an open, fair, and most importantly, pluralistic election in 2020 would be the greatest legacy Ouattara could leave his country. With a renewed electoral mandate and support from both the country and the international community, Ouattara may just be the man to ensure that Côte d’Ivoire doesn’t splinter once again.

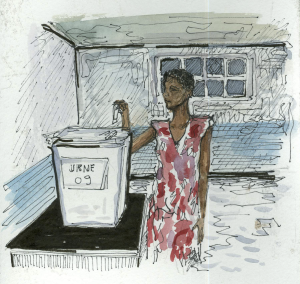

Art by Emma Lloyd