In a protest about the Eastern Bloc’s future, the public station Polskie Radio wasn’t just handing out tote bags. The station played the Polish national anthem and the EU anthem on an alternating schedule. These patriotic medleys were a symbolic protest against a series of controversial laws passed by the Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS, following its victory in Poland’s fall 2015 elections. Already, in its first months in power, the PiS — an ultranationalist, conservative party — has enacted a series of changes that pose a threat to the democratic fabric of the nation. Chief among these are a new set of laws governing public television and radio broadcasters, replacing the old executives with party loyalists who say nary a negative word about the government.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Poland has stood as the archetype of formerly communist countries smoothly transitioning to democracy. The largest Eastern Bloc state, Poland is also one of the more recent additions to the club of global democracies. But the actions of the PiS have threatened the nation’s two decades of strong, institutional democracy. Given Poland’s vital leadership in the region, the EU must address the grave and present threat of a democratic backslide — or risk a huge potentially damning setback in a decades-long effort to liberate Eastern Europe.

Like many radical parties, the PiS cloaked itself in moderate garb during its electoral rise, tapping into a sense of economic hopelessness among young people and those living in rural areas. This sense of hopelessness, exacerbated by a ruling party beset by scandal and overindulgence, made the PiS’s message a perfect fit for the political climate. Earlier in 2015, the party’s Andrzej Duda won the presidency by running on an economically populist message that appealed to ordinary Poles’ frustrations. The newly-elected Prime Minister Szydlo employed these same techniques in the fall, leading the party to success by promising a monthly child allowance, free prescription medications for the elderly, a lowering of the retirement age, and tax write-offs for small businesses. Szydlo focused primarily on economic issues, clearly staying away from the nationalist foreign policies and conservative social policies that the PiS normally emphasizes. It was a clever strategy: The PiS portrayed itself as both the party of change and as a changed party.

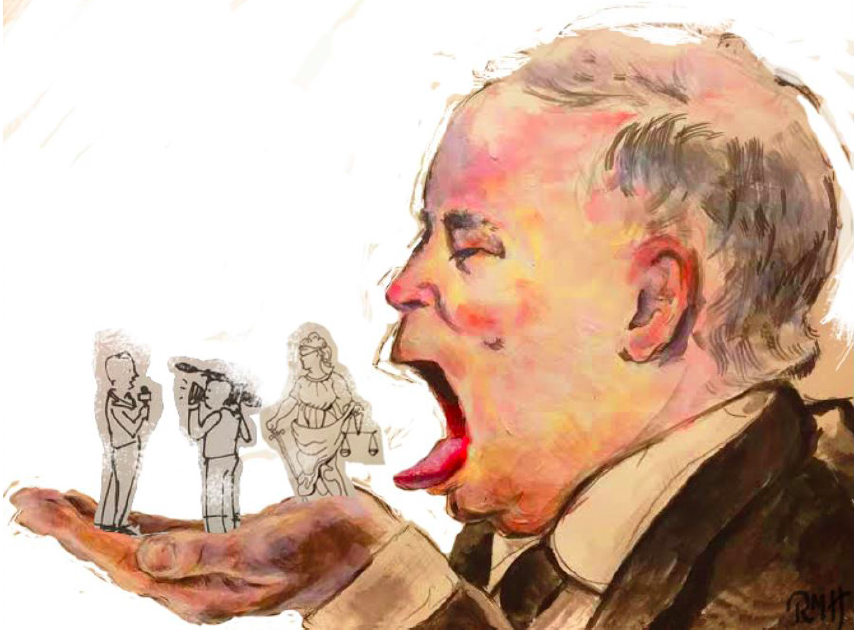

However, as soon as it came into office, the PiS reverted to its old self. Although Szydlo and Duda are technically the heads of government — and therefore heads of the party — they don’t seem to be calling the shots. Instead, at the helm of political decision-making is former prime minister and party leader Jarosław Kaczyński, who still serves as chairman of the party. Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz, a former prime minister, who served under Kaczyński in the mid-2000s, said, “[Kaczyński] has built himself into this head of state without any real position, and this is very comfortable for him. He has no direct responsibility and is free to change the pawns on the chess board.” Although Szydlo and Duda seem to represent a new era for the PiS, Kaczyński still adheres to much of the ultra-conservative, nationalist ideology of the party’s past. His role in pushing his agenda seems evident in several recent actions by the government. On November 25, just days into the PiS reign, the government nullified the appointment of five judges to the 15-member Constitutional Tribunal made by the outgoing Civic Platform government. Duda refused to inaugurate three of the judges, and the PiS quickly appointed five new judges to fill the vacancies. The court responded by finding three of the five appointments illegal. Not to be outdone, the PiS later raised the requirements for the court to declare a law unconstitutional, undermining the democratic system of checks and balances in the country and neutering the court. With a higher bar to overturn legislation, most legislation passed by the PiS going forward will likely stand as long as the party is in power.

To help craft that legislation, Kaczyński has planted government loyalists in key positions around the country. On its second day in power, the PiS appointed Kaczyński’s close personal friend to lead the intelligence service – a friend who had to be pardoned by Duda before the appointment because he was previously found guilty of abuse of power. The PiS has also replaced the heads of the Warsaw stock exchange, several state corporations, and many other civil servants. It has even gone so far as to pass legislation to make it easier to sack civil servants in all parts of Warsaw’s bureaucracy.

However, the most publicly-vilified reforms were those regarding public broadcasters. Silencing government criticism on the airwaves has become a symbol of Kaczyński and his party’s authoritarian overreach, and it has sparked widespread protests and an active investigation from the EU, along with comparisons to Viktor Orbán, the illiberal leader of nearby Hungary. Ironically, Kaczyński has shown admiration for Orbán: The two men met privately in January, talking for six hours. Taken together, the actions of the PiS represent an intentional move to centralize power in the hands of the ruling party — and, specifically, in the hands of Kaczyński.

The PiS’s threat to democratic institutions doesn’t only have ramifications domestically; it’s also a blow to the immense progress Poland has made toward becoming a democracy. When the Soviet Union started to collapse, Poland quickly escaped the USSR’s orbit and sprinted toward democracy, becoming the first Eastern Bloc state to approve a non-Communist government in 1989. A decade later, Poland, along with the Czech Republic and Hungary, became the first Warsaw Pact state to join NATO; in 2004 it was in the first class of Eastern Bloc states to join the European Union. Quickly, Poland became a sterling example of what a former communist state could look like. As the largest of the former communist states to enter the EU, both by population and size of the economy, Poland’s impressive democratic record has served as tangible evidence that the eastern and central European countries can successfully hold onto democracy and rule of law. The country even ranks ahead of the United States and the United Kingdom on the Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index. In short, what’s happening in Poland shouldn’t be happening. But as troubling as the PiS’s actions are for the Polish people, the current state of affairs displays the ever-present risk for young democracies: A slide back into authoritarianism is always just an election away.

To be perfectly clear, the PiS’s actions have not represented the will of the Polish people. A poll by the Taylor Nelson Sofres (TNS) Institute in January showed that the PiS has approval ratings of only 27 percent, down from 42 percent at the beginning of December. While this may seem odd in light of its electoral victory just months before, it’s important to note that the PiS won less than 40 percent of the vote and just over 50 percent of registered voters turned out. That equates to less than one-fifth of all registered voters actually expressing support for the party. Nor have Poles been quiet about their discontent with the PiS’s illiberal actions. After almost every major legislative move, thousands of Poles have gathered to protest, with about 20,000 gathering for the third time in Warsaw, Lodz, Berlin, London, and Prague on January 27. These protests are drawing citizens across age, class, and regional divides, as many fear that democratic backslide will impinge on their way of life.

International institutions need to play a larger role in steering Poland away from authoritarianism. To its credit, the European Union has not been silent about the actions taken by the PiS. In a letter addressed to the Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs, Frans Timmermans, the First Vice President of the European Commission, invoked the “rule of law” mechanism. Adopted by the EU in 2014 to address threats to democracy in any EU country, it states that the European Commission, the EU’s executive body, can initiate dialogue with the violating country in an attempt to prevent any further threat, but its power stops there. And indeed, Timmerman’s letter was an attempt to begin this dialogue, although the Polish government has been unresponsive to date.

If the PiS continues to refuse engagement, the EU will need to act boldly — and, luckily, it has the authority to do so. The European Council, a body composed of the heads of state of all EU members, in addition to the president of the Commission and the elected European Council President (a position coincidentally held by former Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk), have more leeway to act in this case. First, the council can begin a “preventative mechanism,” which is effectively a warning before a “serious breach” has occurred. If a serious breach has been in place for some time, the Council can begin a “sanctioning mechanism,” which would allow it to suspend certain EU rights, including voting rights for the harshest offenders. Neither mechanism has ever been used, and it seems unlikely that they will be, since each requires the unanimous consent of the remaining EU countries. However, the council should consider threatening to use them.

Additionally, the EU may have leverage with Poland through foreign policy, like Poland’s request for further defense support against Russia. More immediately, the EU can also coerce the PiS by threatening to end subsidies during its yearly financial framework review. While these methods may seem to only further enrage the largely Eurosceptic PiS, a Pew survey shows that 72 percent of Poles have a favorable view of the EU. With the growing protests and opposition within the country, an EU effort to use its leverage over Poland and apply strong pressure on the PiS would likely halt the move toward illiberal democracy.

Regardless of which option the EU chooses, the fact still remains that the PiS is instituting a dangerous, illiberal program, one that will likely reverberate beyond its borders. Poland plays a key role in demonstrating the success of democratization in eastern and central Europe, meaning that if any modicum of success Poland has seen to date were to be erased, it could be a warning that democratization was only a Band-Aid on a larger wound. In any case, the decline of a once democratic nation would not be a positive force for democratization elsewhere. Because of this, the European Union must pressure the PiS to act according to democratic principles both internally and externally. Hopefully then, Polskie Radio will be able to return to its regularly-scheduled programming.

Art by Roland High