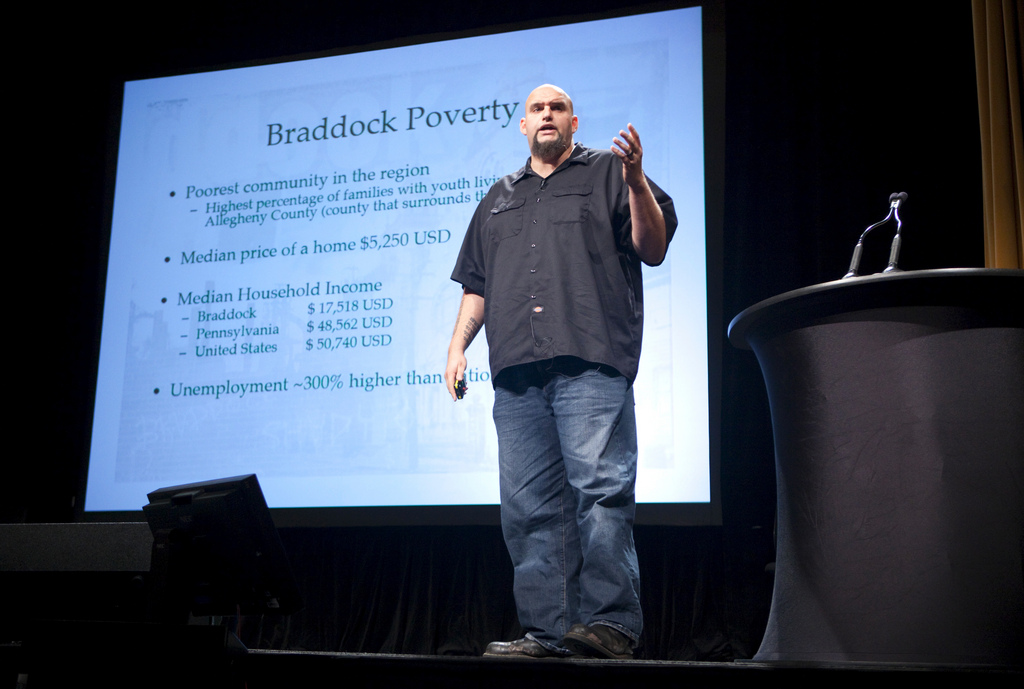

John Fetterman is Mayor of Braddock, Pennsylvania, a town—near Pittsburgh—that once was home to Andrew Carnegie’s first steel mill and a thriving population of 20,000. Today, with some 2,000 residents, over one-quarter whom live in poverty, Fetterman has brought national attention to the town and the efforts he has helped to lead in reviving it. With hopes of bringing post-industrial towns like Braddock into the national conversation via his unique progressive stature—both figuratively and literally—Fetterman is currently running to be Pennsylvania’s next Lt. Governor.

How can American society reframe our political dialogues at the local, state, and national levels to support communities like Braddock as industrialism declines across the nation?

That’s what [this campaign] is trying to be about. We are coming from a marginalized place and community. These places need somebody; we’ve got to make it about these communities too. I’ve lived in Seattle, I’ve lived in Boston, I’ve lived in D.C., and those places are going to be fine, but, to me, there are a lot of places in danger of being left behind.

I’m worried that there are whole segments of our society that are going to break off and start drifting away. My biggest anxieties are places like McKeesport, places like Butler, places like—take your pick—all these places across Pennsylvania. What do they look like twenty years from now? The only thing that has made a difference in Braddock has been resources, attention, and investment. For far too many small government officials in Pennsylvania, the best that they can hope for is to manage the decline, and in a lot of places they can’t even do that, and that’s what makes me sad.

How do you envision using Pennsylvania’s Lt. Governorship for places like Braddock?

The only value in a position like Mayor of Braddock is the platform that it affords you to champion the ideas and the community and the belief that these places genuinely matter. And if you are able to make positive changes and make progress in a place where there hasn’t been anything but forty years of straight decline, I think that that is an important message that needs to come out. Braddock is a small place, whereas when in a statewide position, there’s a lot of scalability there. It’s about visibility. It’s about reimagining what the office is capable of doing. The issues that we care about can manifest themselves on a statewide level.

I want to be someone with a statewide voice coming from a region like this. My issue with politicians is that they come from a certain class of people then pay consultants to make themselves relatable to working class people. Why not just start from that place in the beginning and be your authentic self? Everyone can relate to a place like Braddock. You may not be living in a place like Braddock but can still care and root for places like it. That’s the essence of why I am running. I hope I never come across as cheesy or disingenuous. It’s not a powerful position or one of any prestige, but it’s meaningful and I think in my own small way important that these kinds of places have a voice.

You offer a unique brand of progressivism. You defied state law in 2013 to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples while still offering a robust defense of what some might call “Trump Country.” What changes do you believe that American progressives must make?

There’s this kind of purity [amongst progressives]: if you don’t agree with me on every single issue, you are now my enemy or are a bad person. There’s this idea that progressivism and pragmatism are oil and water and that you can’t be both. The only way Republicans can win is if [progressives] start in-fighting about who is more devout, instead of saying that there are things we will never compromise on and others that we can. I’m not saying be some spineless person who doesn’t stand for anything. You can be principled and at the same time acknowledge that if you don’t have a seat at the table, you are on the menu.

We are the same nation that overwhelmingly chose Barack Obama over a decorated war hero in John McCain and a movie star, handsome Republican [in Mitt Romney], and neither race was close. What made Donald Trump possible was that we left far too many people behind and they were left with this idea of “what do I have to lose? He’s out here talking to me, and I haven’t seen [Hillary].” I think most of his voters don’t like the fact that he mouths off on Twitter. They just want to know that they’ve got someone who looks out for them. I’m not saying Trump does. At the end of the day, they are almost always decent people.

What lesson can the country learn from Western Pennsylvania?

[Journalist] David Templeton did an article in the [Pittsburgh] Post-Gazette where he compared McKeesport and Upper St. Clair. They’re both in Allegheny County; they’re both an equivalent size. And McKeesport has a decade less of life expectancy than Upper St. Clair, and you can drive between the two in fifteen minutes. Even in Allegheny County, you have developing nations health outcomes. We are creating two separate societies within one overall society, and that really frightens me. When you’ve just assigned $1.4 trillion to a giant tax cut that benefits a very select group of people and then there are places like McKeesport left behind, I just find that indefensible. I don’t know why it doesn’t bother more people. Talent is equally distributed; opportunity is not.