Under the guise of an anti-terrorism campaign, the Chinese government has established Muslim detention and re-education camps in the northwestern Xinjiang. In reality, this practice is a form of cultural erasure that aims to replace practices and names that do not reflect traditional “Chinese” heritage to assimilate all under a “great rejuvenation of the ‘Chinese’ nation.”

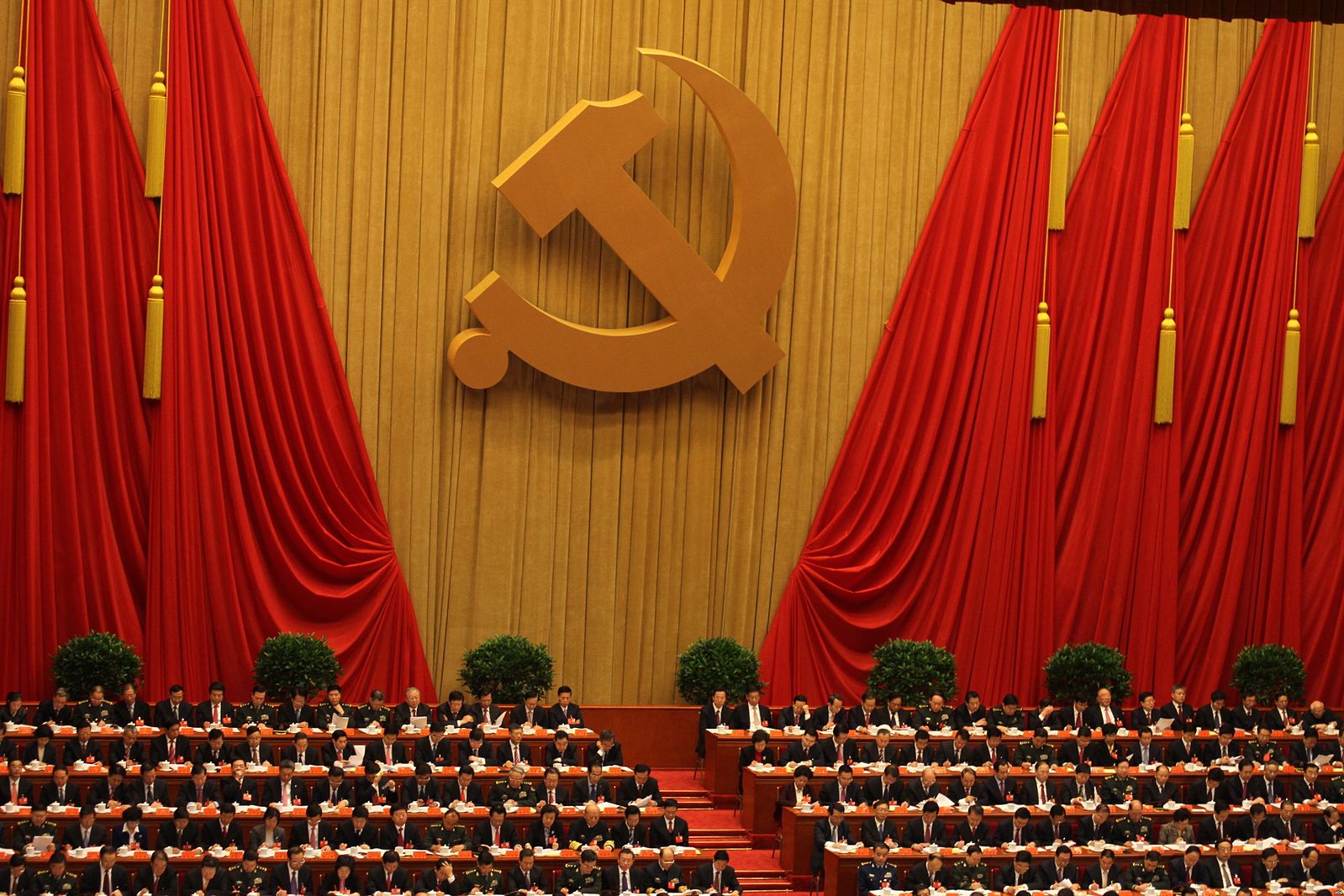

This assimilationist ethnic policy has been spearheaded by General Secretary Xi Jinping, who regularly exploits revolutionary idealism to legitimize his rule. Under Xi, the party has frequently drawn on the legacy of the 1949 Chinese Revolution to justify its actions. Slogans such as “never forget our original aspirations, firmly keep in mind our entrusted mission” bring the Revolution’s messages into public spaces throughout China. Xi even referred to his official ideology as the continuation of China’s “great socialist revolution.”

But the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s attempt to assimilate ethnic minorities under a nationalist “Chinese” label stands in stark contrast to its stated goal of reviving revolutionary ideals. In fact, China’s aggressive policy toward ethnic minorities is not only bad on face, but also politically dangerous. Such a policy betrays the promises the CCP made to minority ethnic groups during the revolution and revives racial ideologies that the revolutionary-era CCP fought against. It is important to prevent the CCP from manipulating history for its own ends by declaring ethno-nationalistic policies part of maintaining the Revolution’s legacy. Indeed, by doing so, the Party is repeating mistakes its former Nationalist enemies made that led to ethnic revolt and rebellion. Following this path again today will erode the potential for a harmonious, multiethnic China.

During the Revolution, ethnic minorities were vital to the CCP’s success. As the CCP claimed governance in 1949, it prioritized the right to self-determination and preservation of the culture of ethnic minorities. On the famous Long March in 1934, the CCP journeyed through regions populated by ethnic minorities where its only option for survival was to negotiate and work with local minority leaders. In exchange for help fighting the enemy Nationalists, the Communists promised to recognize the unique ethnic identities of minority peoples and protect both their cultures and languages. After the CCP victory, the Common Program of 1949 codified these promises into law, guaranteeing regional autonomy for ethnic minorities, protection of their languages and cultural practices, and full recognition of minority nationalities by the central government.

This respect for ethnic minorities aided the Communists’ victory because of its stark contrast with the Nationalists’ approach. The Nationalists pushed for an assimilationist policy designed to mold a “single-nation race,” which lost them the support of minority groups. The Communists seized this opportunity, championing minority rights to build a broad coalition of people opposed to Nationalist policies. These tenets persisted once the Communists took power. During a famous 1956 document written by Chairman Mao Zedong, he stressed to his comrades the importance of “combatting Han Chinese chauvinism” and rejecting the “bullying” of minority peoples.

Of course, the CCP’s early ethnic policy was not entirely beneficent. The Party often used the central government to tightly control “autonomous” minority governments, and there is ample evidence that the goal of its autonomy pledge was to maintain the territorial unity of China, not to deliver true self-governance. But despite its flaws, the relatively benevolent attitude of the revolution-era CCP towards ethnic minorities is starkly different from the Sinicization measures being pushed by the government today.

In Xinjiang alone, current reports have documented numerous attempts to impose severe restrictions on the practice of Islam, the use of the Uighur language, and the performance of traditional arts. Scholars of Uighur culture and writers reporting on the Uighur community have suddenly disappeared. The Chinese government has begun to openly push and defend Sinicization in Xinjiang through press releases, documentaries, and op-eds, publicizing its intent to remold Uighur cultural practices and painting them as an ethnic group susceptible to radicalization and in need of modernization.

In stark contrast, Islam in Xinjiang flourished in the early 1950s, though it was more intensely regulated. Efforts to follow through on promises to the Uighurs led the state to support Uighur-language schools and recognize key heritage sites and art forms. The government placed Uighurs in decision-making positions previously only held by Han Chinese officials and chastised Han Chinese people who belittled minorities or otherwise contradicted the ideal of interethnic equality. Today’s government, despite its rhetoric to the contrary, is worlds removed from practicing what the CCP originally preached.

The CCP gives two main justifications for its current policies towards ethnic minorities. The first is that the detention camps can combat the rise of Islamic extremist ideology, which they argue is present in Uighur Islamic practices. The second is that assimilation is necessary for ethnic unity; on this view, China can be stable and prosperous only when a single Chinese-nation race is cemented. This belief, which arose in the early 2000s after significant ethnic unrest in Xinjiang and other places during the 1990s, became solidified as state policy under General Secretary Xi in response to another bout of ethnic violence in 2014.

These arguments, though problematic, are neither novel nor implausible. But claiming that the motivations behind the push for assimilation are faithful to the ideals of Chinese communism is deeply hypocritical and dangerous. By using the same language of assimilation and “single-nation race” that the Nationalists did before Communist ascendency, the CCP under General Secretary Xi looks and acts like its former enemies, employing the same “bullying” approach to ethnic minorities it derided in the past. This about-face could have serious political consequences. After all, the Nationalists’ inflammatory ethnic policy undermined its rule and contributed to its fall from power. The two successful ethnic rebellions that occurred in Xinjiang under Nationalist rule were reactions to harsh bans on Islamic practices and ruthless purges of minority leaders. If the CCP looks and acts like the Nationalists in the ’30s and ’40s, it risks reliving their mistakes, fomenting ethnic conflict, and delegitimatizing its own rule.

Still, General Secretary Xi continues to evoke the revolutionary past to link his rule to the glory of the Communist liberation. But the radicalization of Sinicization policies makes clear that the current government is betraying the CCP’s original promise of minority group recognition and is reverting to the ethnocentric ways that the Party campaigned to abolish. The CCP is going down the path of “Han Chinese chauvinism” that Chairman Mao warned about in 1956. Both Mao and history tell us this chauvinism will weaken the state and exacerbate ethnic tensions. Far from leading a “national rejuvenation,” Xi’s policies will leave the Chinese Revolution’s hopes of a harmonious multi-ethnic China to die.