The American vote is broken. The solution may not be to bring the people to the polls, but rather to bring the polls to the people by allowing them to vote at home.

The 2018 election cycle revealed that weaknesses continue to exist in our current election system. We have not yet perfected the process of voting; 2018 saw widespread voter suppression, discrimination, and disincentivization. Cases of voter suppression regarding missing ballots and widespread discrimination are currently being carried out in North Carolina and Georgia, and without changes to the system in place currently, these barriers will only continue to obstruct voters and erode confidence in our electoral system.

These issues are by no means new: voter suppression has occurred over the course of our country’s entire history. Dating back to the Jim Crow Era, racial minorities have been targeted at the polls and purposefully excluded from casting a vote. Socioeconomic voter suppression happens across the country as well, as people who are not able to take time off of their jobs simply do not get a holiday or break to vote. People are being, and have been, prevented from voting because of who they are, plain and simple.

Not only is voter suppression rampant, but even those who are able to vote are failing to show up at the polls. In fact, voter turnout in the US lags behind other similar countries, and in the 2018 midterm election less than 50% of registered voters actually voted (60% voted in 2016). The essential foundation of our democracy is the right to vote; the fact that people are being prevented from or simply are not exercising this right highlights how necessary reform is.

One possible solution to this widespread, hot-button issue is at-home voting. The idea is exactly what it sounds like: People are allowed to vote at home, without ever having to go to a physical polling location.

The system is opt-out: All registered voters are automatically sent a ballot via mail, which they can fill out and return via mail or a physical polling location if they still want the American tradition of going to the ballot box. The process is simple and transparent, and solves many of the issues that are currently plaguing our election and voting systems.

Voters who cannot take time off work during the day to go to the ballot box can simply fill out their ballot via mail and send it back via mail. Socioeconomic background might no longer stand as a barrier to showing up to the poll and exercising one’s right to vote. Other issues could be taken on with at-home voting as well, as voter suppression often takes place at actual polling locations, especially for people of color in the American South. Without actual polling locations, the problems of long lines and physical voter suppression could drop dramatically.

But how do we know this system could actually work? Look West: Oregon and Washington state have already taken up at-home voting, and have seen significant increases in voter turnout, outpacing surrounding states by a considerable margin. In fact, Oregon had the single highest voter turnout of any state, with 63 percent of registered voters turning in a ballot. Increases in turnout were actually most pronounced among people under the age of 25, a population with historically low turnout in comparison to their elders. These states are proof that implementing this new system of voting is not only feasible, but actually beneficial. While states, and their voting systems in turn, are obviously different, these two are proof that setting up this infrastructure and bringing the vote into people’s homes is a distinct possibility.

However, at-home voting is not a perfect system; several politicians and policymakers have raised suspicions about the process. They point out the possible issues of voter fraud, large-scale takeovers, and general infeasibility. In particular, many critics of the systems in Washington and Oregon point out the large homeless populations in Seattle and Portland that do not receive ballots in the mail due to a lack of a permanent address. Greater issues with a lack of infrastructure and lack of funds to power this new system have been raised by politicians on both sides of the aisle.

In terms of voter fraud, Oregon and Washington have shown that this is not much of an issue at all with at-home voting; voter fraud cases have been extremely rare since the implementation of the system in the states, and have even been more rare than many other states with traditional voting systems. As for the exclusion of homeless populations, Portland and Seattle have realized this issue and have taken up city-wide programs specifically to make sure that homeless populations are receiving their ballots just as often as people with permanent addresses. They have established registration drives at community centers, post offices, DMVs, social services offices, libraries, and more in order to make sure that people without permanent addresses registered with the state are able to vote, and their efforts have been shown to increase registration among low-income and homeless populations significantly.

Objections to a greater systemic shift may also come from a larger sense of American democratic traditionalism; going to polling locations has been emblematic of American democracy since it began, and many do not want to see this go. The ‘I Voted!’ sticker and the experience of physically walking into the polling station is inextricably tied with the act of voting itself for many Americans who have done so for their entire lives. But at-home voting does not prevent this. People are still allowed to bring their ballots to polling locations if they so choose, but they are also given the ability to vote if they do not have the ability to get there on election day.

Some Democrats have suggested that fixing the current system, rather than implementing a new one, is the solution. With the recent passing of HR1 in the House, a bill that calls for widespread changes to the current voting system, this style of reform looks to be the likely direction of the party in the near future. However, it is important to remember that this larger style of voting reform and at-home voting are not mutually exclusive, but rather can coexist to further solidify our most basic democratic right. At-home voting can be part of a larger package of democratic reform, and it could very possibly address some of the biggest problems with the current system.

At-home voting is not perfect by any means; it has its critics, and it has its shortcomings. However, we cannot sit idly by and watch as our voting system turns into one of suppression and low turnout.

Whether it is at-home voting or some other system of reform, something has to be done to secure the most sacred right of Americans: the vote.

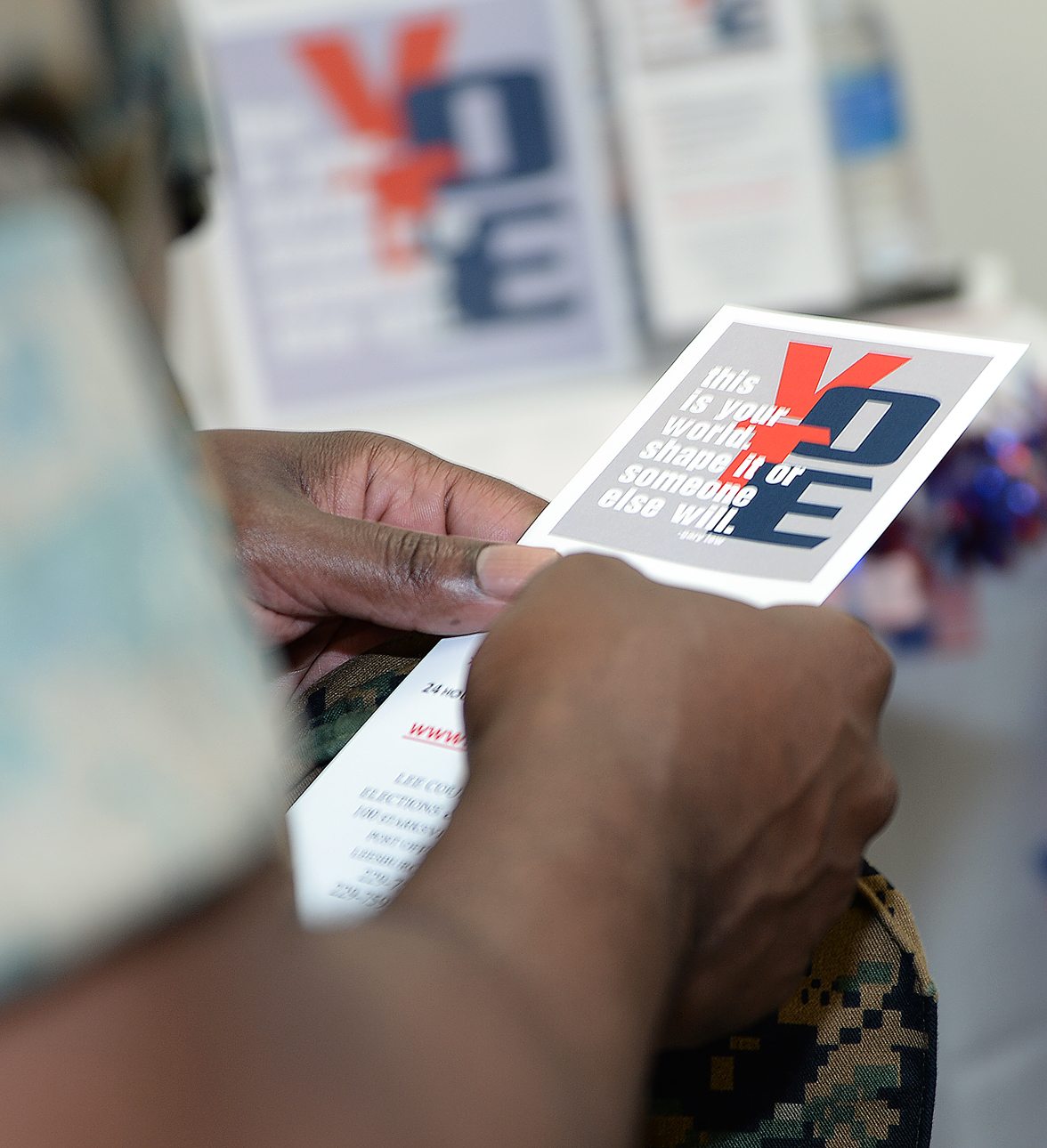

Photo: “Voting Literature“