Beds are running out at Ek’Abana, a shelter for abandoned children nestled in Bukavu, the capital city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC) South Kivu Province. In 2018, an Ek’Abana representative attributed the orphan- age’s dwindling capacity to an influx of young South Kivu residents banished from their homes following accusations of witchcraft. One resident, 16-year-old Aline Veronica, sought refuge at Ek’Abana after a witch doctor convicted her of casting a deadly spell on her neighbor’s son and she was forced to flee for her life.

Thousands of miles away, a similar phenomenon is devastating another community. In Gujarat, a state in India, approximately a dozen women gather at ANANDI, a nonprofit working to support and empower rural Indian women— especially those branded as dakan (the Gujarati word for witch). In one notable instance, three Gujarati women accused of eating the souls of their male relatives were subsequently beaten nearly to death, forced to give up their land, and made to live with their abusers. In the wake of horrific events like these, home is no longer a safe place to live for the Gujarati women, nor is it safe for witch hunt survivors in other parts of India, the DRC, and beyond. Thus, local and federal governments must take immediate action to protect the women and children whose lives are threatened by these deadly witch hunts. While implementing nation-specific laws both banning witch hunts and declaring witch hunting a motive for murder are worthwhile preliminary steps toward ending witch hunts, these efforts must be paired with education programs built by and for communities where witch hunts run rampant. Witch hunts are not isolated incidents, nor are they localized: They affect people—most often women—in many regions of the world, from Southeast Asia to Africa to Latin America.

In India, for instance, more than 2,500 people were murdered in witch hunts between 2000 and 2016, most of them women from a low caste. In Tanzania, between 1960 and 2000, around 40,000 people were accused of witchcraft and killed. In Ghana, about 1,000 women live in “witch camps,” settlements where women accused of witchcraft can flee for safety. And in the DRC, as of 2015, a staggering 20,000 Congolese children were living on the streets, an estimated 80 percent of whom were doing so because accusations of witchcraft forced them out of their homes. Though these numbers are horrifying already, experts warn that witch hunt-related murders are grossly underreported, especially in countries like India and Tanzania where witch hunting is not nationally outlawed.

While witch hunts are clearly a widespread phenomenon, the motivations behind this brutality vary drastically from country to country. One of the most common explanations, however, points to witch hunts as a form of gender-based violence. In India, for example, not only do women make up the majority of victims of witch hunts, but witch hunt survivors also draw a clear connection between witch hunts and gender violence. Many accused women recall being branded as a witch not because they caused harm to others, but because they broke gender norms by inheriting land or refusing a sexual advance.

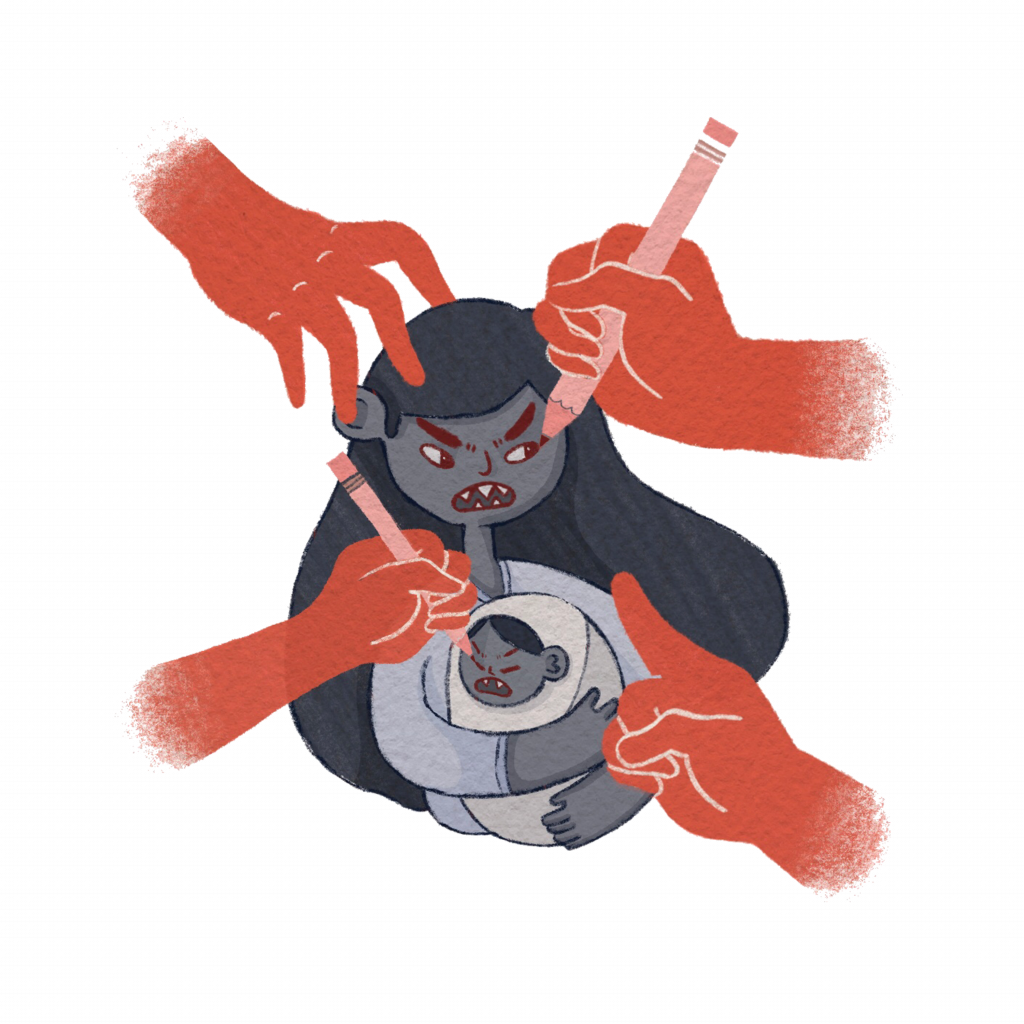

Witch hunts must be confronted as an issue of gender-based violence against typically older women in places like India but this is not the case everywhere. In fact, the DRC is facing a crisis with entirely different victims: children. The rise in reports of child witches began in the early 1990s, paralleling a similar increase in overall violence toward children. Even in recent years, young survivors recount being condemned to death by their own families or tortured through “exorcisms” meant to drive out the devil.

According to researchers, this abhorrent violence against children in the DRC can typically be attributed not to gender violence, but to economic hardship and rapid urbanization. As the poorest country in the world, the DRC struggles with prolific poverty, and children—especially those who have lost one or both parents and live with extended family members—are often seen as a costly burden for already struggling families. Issues like death, illness, or unemployment, all of which are exacerbated by a sudden shift to urban life, also tend to be blamed on children. Thus, the persecution of children through witch hunts can be attributed to larger socio-economic problems in the DRC.

Even as gender-based violence and economic struggles are the sources of many witchcraft accusations, superstition is another factor motivating witch hunts in many countries. Often, women and children serve as scapegoats for problems like droughts and crop failures, and people see witchcraft as an explanation for the misfortune befalling their communities. Disease and disabilities are often attributed to witchcraft too, especially in nations that lack strong healthcare infrastructures. In Tanzania, for example, people with albinism are frequent victims of witch hunts, and in Ghana, witchcraft is a common explanation for the birth of children with disabilities. These superstitions must also be acknowledged in the fight to protect women and children from witch hunts.

Undoubtedly, the violence and terror caused by witchcraft accusations need to be addressed. Especially in places like India, where bans on witch hunts are determined by individual states, it is imperative that a national law is implemented that recognizes witch hunts as an illegal form of abuse in order to hold attackers accountable in a court of law. In places like the DRC, where a similar law already exists banning witchcraft allegations against children, law enforcement officials must stop turning a blind eye to abuse committed by families and churches as they usually do. Instead, they should take responsibility for the protection of women and children and the punishment of abusers.

Although establishing and enforcing these laws is an essential first step toward curbing witch hunt-related crimes, legislation alone is not enough. In India, some states that have outlawed witch hunts still see dozens of related murders each year, and the DRC is no different. This is partially because witch hunts are a deeply entrenched cultural practice, built upon gender-based violence, economic troubles, and superstition. When nonlocal groups work toward solutions to end witch hunts, they might do so with the conviction that supernatural beliefs are inherently false, while ignoring the fact that these superstitions are still an essential part of other cultures. Thus, local leaders must spearhead efforts to educate their communities on the harmful impacts of witch hunts, reunite accused women and children with their families, and outlaw witch hunts in totality. With a full grasp of their region’s cultural practices, community leaders can create lasting change that prioritizes the safety of the victims of witch hunts in India, the DRC, and beyond.