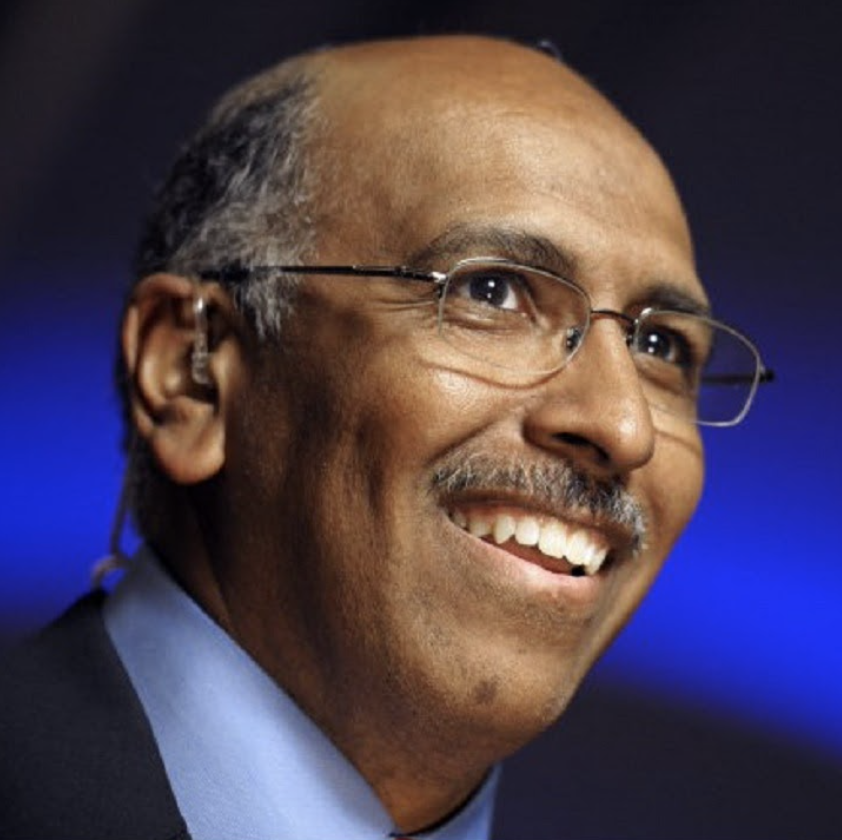

Michael Steele made history as the first African American Lieutenant Governor of Maryland (2003) and chairperson of the Republican National Committee (2009). During the 2020 presidential election, Mr. Steele became an advisor for the Lincoln Project—a culmination of his long-standing criticism of President Trump. In addition to his role as a Watson Senior Fellow at Brown University, Mr. Steele makes regular appearances on MSNBC as a political analyst. Currently, Mr. Steele is considering running for governor of Maryland in the upcoming primary.

Alex & Haley: The Republican Party continues to embrace a kind of Trumpist rhetoric on issues of identity and race. Is this a sustainable electoral strategy for the Party, especially in a country that is becoming increasingly diverse?

Michael Steele: No, it’s not. The Republican Party is placing its future political bet on white voters. Period. You can’t sugarcoat it. The Party has failed to acknowledge that the country is going to look more like me in less than 20 years. Despite what people may think, the demographics are changing, and so are the attitudes of young white voters as they begin to see through a lens very different from their parents—certainly different from their grandparents. The Party’s strategy can not stand up against this new reality of demographic change and social awareness.

There’s something good about becoming self-aware. Everyone got their nose out of joint about the 1619 Project because for the first time Black folks told their side of history, and white folks lost their mind. People said, “Oh, well that’s not academically correct.” Well it is! We’re telling our story; you don’t get to tell our story anymore. So this awakening—not just in the Black community, but for women, Hispanics, Asians, gay people, and all of the various pieces that make up this thing called America—is a frightening thing for those who don’t want to recognize it.

There is a fear of recognizing that in my Party right now. So they hold on to that 1950s view of America, a view that never really existed: the white picket fences, daddy going to work, mommy staying at home, a Chevy in the front yard, the flag flying on the front porch. It’s the “make America great again” narrative. And you could take out “great” and put in “white” and it would still mean the exact same thing. How do we know that? Well, we’ve embraced the Proud Boys. We’ve embraced Nazism. We’ve embraced white nationalism. We have not pushed back against it as we once did. When Senator Goldwater gave his segregationist speech at the 1964 Convention, a lot of Republicans were like, “Hell no, that’s not who we are. We’re not doing that,” and they didn’t vote for him. That’s how he lost. So you can see how the politics have changed, and so the question for the Party becomes: how do you lean into that? How do you step into those changes and reconcile yourself within a country that looks less and less like you?

60,000-65,000 Hispanics turn 18 years old every month in this country. How do you think those voters are gonna vote if we call their relatives murderers and rapists, and say that we’re going to build a wall to keep their cousin from coming here and that we’re going to separate their brother from their mom, and put him in a cage? How do you unwind all those narratives that have been created? So you’ve got to start from the beginning and recognize what you’ve done as a party and what some of your politicians have done, individually, to perpetuate racist narratives.

A&H: In an interview with the Baltimore Sun, you described your difficult relationship with the Republican Party in the form of an extended metaphor: “If you come to my house and, in the course of being there, you start tearing up my carpet and writing on my walls and breaking my fine china, do I throw you out or do I leave?” At what point do you leave your house? Is there a clear threshold for you?

MS: These questions are at the forefront of a lot of Republicans’ minds right now. We’re at that reckoning moment where we have to assess whether or not the infestation of Trumpism has become too deep and terminal. I’ve said that I’ll stay in the fight for as long as I can—as long as there’s value in the fight. And I know that there are a lot of Republicans who don’t want to leave for a whole host of reasons, so you’ve got to help them and be respectful and mindful of why they stay.

The next question is what are our options? The Democrats have not offered Republicans like me a reliable alternative because politically, they’re beyond dysfunctional, and on policy, they’re not very welcoming. And our political structure doesn’t allow for other voices to land someplace else. After all, we only have two parties in this country…

But why do I stay? Because I know it pisses people off. They weren’t there when I joined in 1976, and I’ll be damned if I let them kick me out now. So they can threaten me and browbeat me and push me around, but I’m not going anywhere. They don’t have that kind of control. They never have.

A&H: It seems like we’re touching on a broader criticism of the US’s majoritarian system. In keeping with your metaphor, the US really only has two houses that promise any kind of electoral success. Do you find the current model to be limiting or problematic?

MS: Yes. It has lost its usefulness for a country that is beyond its agrarian, white-male-dominated origins. Just go back and look at what the Founders said about our political system and political parties—they didn’t want it.

That’s why they formed a Republic of independent colonies that bannered themselves under this idea of being united. Our first founding document was the Articles of Confederation where we agreed to work together, right? So our Founders were very wary of a political system that would become dominated by factions. And we have lived true to their concerns and their doubts, from Madison to Washington. So the system has to fundamentally change. We cannot sustain ourselves as a Republic under this current system. In fact, a republic almost demands pluralism in our parties, because it’s going to be the closest to representing all of our values.

A&H: Given that the two-party system is likely here to stay, is there anything the Democratic Party can do to welcome alienated Republicans into its ranks?

MS: That’s a good question. I’ve had close relationships with many Democratic chairs, and I’ve said to all of them, “Who is your Reagan?” Reagan pulled Democrats to the Republican party and kept them there for 10 plus years. How did he do it? What was his messaging? This idea of a Reagan Democrat has some real value to it.

Currently, who is that political figure who recognizes that there are Republicans who probably would align themselves with the Democratic party? I mean, if a pro-life Republican like myself became a Democrat, I wouldn’t expect the Democratic party to become pro-life. But damn, could they at least acknowledge that they already have some pro-life Democrats? They make it seem like no such creature exists in politics. I know a lot of pro-life Democrats, but even they feel stunted in their ability to express that openly because they get shouted down and labeled as anti-women, and that’s just not the case.

So the reality, politically, is what can the Democratic Party do to make it attractive for me, a Republican, to join forces with them?

A&H: On the subject of abortion, many Republicans feel as though the all-encompassing decision of Roe v. Wade was overreaching, and that abortion law should have been left to the states. However, wouldn’t allowing state legislatures to decide abortion laws nonetheless infringe on personal freedom?

MS: How is it an infringement on personal freedom if the citizens within that state decide that they all agree through referendum or their elected officials? I live in a state where abortion rights are enshrined in our constitution. I have a choice: if I’m so offended by that, I can leave my state. But we decided back in ‘92 through a constitutional referendum to make that change. That’s an appropriate state action, and that’s what the Constitution allows.

The problem with the abortion discussion is that it was decided prematurely, in my view, by the Supreme Court—it had yet not matured within the States. By the time the Supreme Court had acted, the debate over the issue hadn’t even been tested legislatively, really, but in a handful of states. So the reality of the question was not ripe for adjudication by the Supreme Court, and therefore the states should have, as they do in all other matters, made their own decisions. And where there is conflict, the Supreme Court can then decide what the constitutional norms should be. But we’ve never had that debate, so let the citizens decide what they want.

When it comes to something as personal as the choice over whether to carry a child to term and all of the dynamics that go into that decision, what makes you think this individual is going to stop because there’s a law that says she must? So we’ve got to be honest and recognize where we are in this space, and my party has played as much of a role in making it a difficult, ugly space to navigate as have the Democrats.

A&H: If the underlying motivation for “leaving it to the states” is to improve representation, why stop there? Why not make it an individual choice in order to fully optimize representation?

MS: Because you’ve got to provide a legal mechanism for that to happen. So in other words, if I choose to have an abortion, then I’ve got to have a legal mechanism in which that choice is protected or allowed to occur, because what if in the community you live in, all the doctors refuse to operate on you?

So you’ve made your choice, but so has that doctor. And so then what? Where does that woman go? What does she do? So there has to be a consensus around what we will allow to happen in this space; we want to take into account individual choices and also those who may disagree with whatever that individual choice is. And that’s where restrictions come into play.

A&H: Perhaps I can clarify the case for individual choice. Let’s look at Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, where the Supreme Court upheld the right for a baker to refuse to bake a cake for a gay wedding. In the same way, why can’t doctors choose to perform or not to perform abortions? That way, we affirm everyone’s personal freedom without imposing restrictions.

MS: The issue there is a little bit stickier because doctors have taken an oath to provide for the wellbeing of a person. So they can not just say no if a woman is in a distressed situation. If a doctor were to object, he may be able to remove himself, but only if someone else could step in his place. So for a rural doctor in that situation, he can’t deny care for a patient, especially if her life is potentially threatened, as well as the life of that fetus.

I don’t have to bake a cake for a gay couple if I don’t want to. And, to be honest, there’s not a law on the books that will require me to do so. That’s just the way it is. But for a doctor in that situation, it’s a little bit different because there are additional obligations related to their role as a medical professional.

A&H: American politics has become increasingly sectarian—especially on issues such as abortion. Does either party have an incentive to combat political polarization, or are there overriding motives to maintain such a divide, if not magnify it?

MS: No, there’s no incentive to combat polarization. All the money is in polarization. That’s the great grift that’s going on right now in our politics. So to give you an example, Marjorie Taylor Greene, a woman who should not be in Congress under any circumstances whatsoever, gets taken off of committee assignments because she is reprehensible and racist. And what happens? She raises $3 million because of it. Someone with no committee assignment—she’s an absolutely useless entity inside the United States Congress. So the system is now rewarding racist, fascist, misogynistic, polarizing behavior.

A&H: What is one of the most important lessons you’ve learned from the campaign trail?

MS: The one thing I would say to any candidate is that if you’re not comfortable with who you are and you’re not firm in what you believe, then you shouldn’t engage in politics yet. You’re not ready, because you have to be prepared to withstand the buffeting that will come—when those forces push up against what you believe in and value.

And look, I know some people hate me. It’s not a question. And you know, I’m fine with that because I like me. So you can hate me ‘til you get sick. I don’t care. That’s not going to change what I think or believe. And I’ll ask the person who hates me for their vote as much as I ask the person who likes me for their vote. I’ve lost elections before, but I’ve come out the other side being able to look in the mirror every night and say, “You’re okay, kid, keep it going.” And if you can’t do that, then you’re just not ready to engage.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.