In 2015, researchers from the US Army Corps of Engineers published findings that, to Chesapeake Bay area residents, were likely unsurprising: Tangier Island is sinking, and fast. A tiny island west of Virginia’s Eastern Shore and the current home to about 400 people, Tangier is highly vulnerable to rising tides and harsher, more frequent storms brought on by rapid climate change. Current estimates predict that the island will be completely uninhabitable by the 2050s, generating hundreds of climate refugees and signaling the beginning of an era where Tangier’s fate may not be all that uncommon. The drowning of the island’s rich culture under the Chesapeake waves represents a history lost to negligence. Our passive indifference will make it no less tragic.

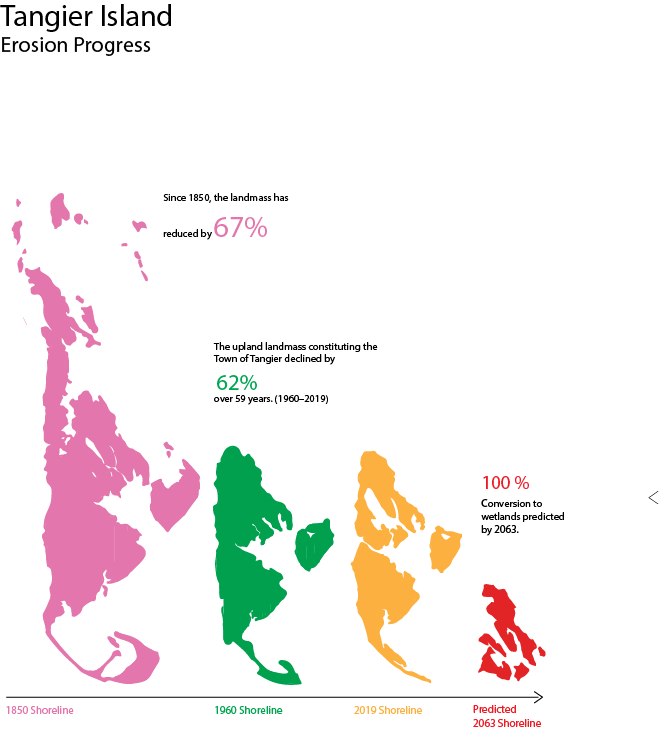

Long before the arrival of English colonists, Tangier was a hunting retreat for groups indigenous to the Eastern Shore, such as the Pocomoke people. The arrowheads still dotting the beaches suggest that a diverse ecosystem flourished on the island for centuries. English colonists displaced many Chesapeake Bay Native communities and drew up a remote fishing and agricultural village largely secluded from the mainland. To this day, the surnames of the island’s residents are a short list, one that aligns closely with the records of those who arrived there centuries prior. Tangier briefly became a place of refuge for enslaved people in the region during the War of 1812 when hundreds fled to the British Fort Albion to trade military service for emancipation. Today’s residents of the island even preserve a distinct English dialect owing to their relative solitude on the open waters of the Bay. The loss of two-thirds of the island’s landmass over the past two centuries has rendered farming impossible, leading the islanders to adapt and embrace crabbing as their primary industry. Unfortunately, Tangier’s rich history seems to be drawing to a close, with pessimistic climate projections dampening any hopes for natural resource preservation.

Policymakers face a uniquely bleak and wildly expensive set of options to mitigate the devastation of Tangier. After decades of inaction, Virginia Senator Tim Kaine and Representative Elaine Luria are currently fighting to secure $25 million to augment the island’s barricades from flooding. While an undoubtedly well-intentioned effort, there is little evidence that this project would do much more than prolong the continuing loss of land mass. The aforementioned US Army Corps of Engineers study predicted that it will cost $250-$350 million to fully protect the island from rising sea levels and $100-$200 million to relocate the island’s residents to solid ground. Given this grim prognosis, it seems unlikely that this federal money would be well spent on such stopgap projects. As one local journalist put it, “Mother Nature seems determined—and destined—to win” the fight against communities like Tangier.

Unfortunately, Tangier will be neither the first nor the last piece of Chesapeake Bay history lost to erosion and rising tides. About 500 islands have essentially vanished since the early colonial period. Despite the severity of the situation, even the Island’s current residents are unsure about Tangier’s future. High levels of doubt regarding the effect of rising sea levels, coupled with the unsubstantiated reassurances by former President Trump that the island has “hundreds of years more,” have severely undermined efforts to sound alarm bells. Tangier Mayor James Eskridge stated that he loved President Trump “as much as any relative [he’s] got” after Trump personally called the Mayor to claim that erosion, not rising sea levels, was the main cause of landmass loss and to encourage them not to worry about tides nor the island’s longevity. Local ambivalence, however, cannot give Virginia’s policymakers complacency in preparing for necessary relocation efforts. Ignoring a crisis does not alleviate its effects: Indifference is in itself a political choice, a mortgage on vulnerable coastal communities. If hundreds of islands with centuries of cultural importance sink into the water, will they make a sound? Will we finally prepare for ecological destruction and the generation of countless climate refugees both in the United States and abroad?

The plight of Tangier might be distant in the mind of the average American, but communities across the nation are facing the same intensifying issues. In 2016, the Department of Housing and Urban Development set aside $48 million to relocate the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Native community away from the increasingly unlivable Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana. The relocation process is also a grim cautionary tale telling us that ensuring equitable distribution of resources to the hardest-hit groups is not nearly as simple as one may hope. Albert Naquin, chief of the local band of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, protested that Louisiana has excluded Indigenous perspectives from the relocation process, asserting: “The state stole our plan to get the money, and now they are running off with it.” Dense urban areas have also borne the brunt of rising sea levels and harsher storms. Staten Island neighborhoods like Ocean Breeze have yet to fully rebuild after Hurricane Sandy ten years ago and have no plan to do so any time soon. The vulnerability of waterfront land devastated by the storm inspired the New York State government to buy people’s land at pre-storm prices. One resident, Joe Herrnkind, decided to participate in the program and permanently relocate from Ocean Breeze, saying that he was “reluctant to put someone else in harm’s way.”

The United States contributes to making Tangier and countless places like it uninhabitable through its reliance on fossil fuels. As a nation, we owe it to climate refugees—including the final generation of Virginians to live on Tangier Island—to offer financial and community support during this transition. Irreplaceable pieces of our cultural heritage may be vanishing before our eyes in the Chesapeake and around the world, but the warning signs of ecological catastrophe are as visible as ever.