Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite was the first South Korean film to be awarded the Palme d’Or. The film uncovers the South Korean class struggle by depicting the Kim family’s fraudulent invasion of the Park mansion and the stark contrast between their residences. While the affluent Park family lives in an architectural masterpiece, the Kims’ minuscule banjiha, a semi-basement style home, offers a realistic and true look at how a vast portion of Seoul’s youth lives.

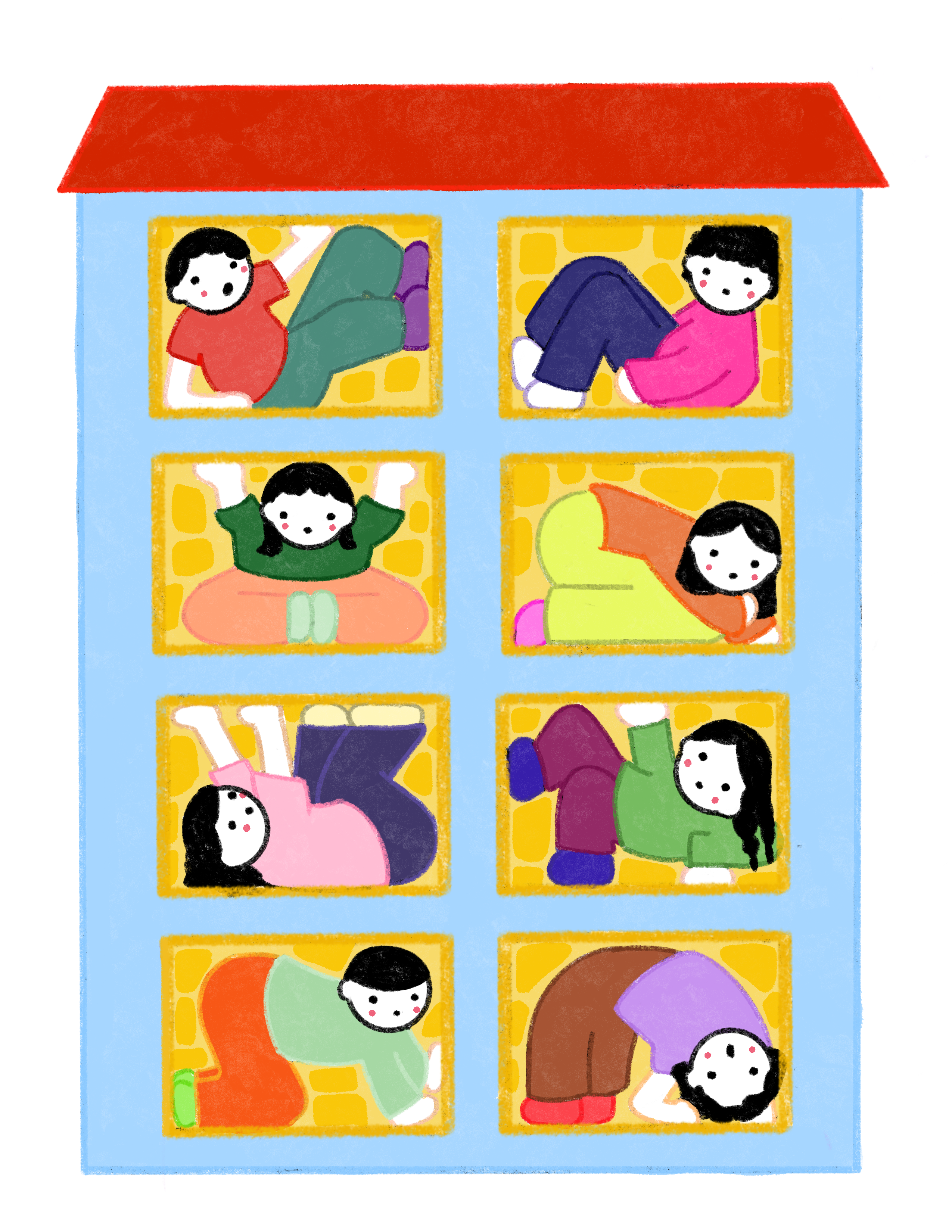

Residential housing prices in Seoul have risen dramatically in recent years—increasing by 6.5 percent in 2021 alone—and have forced many young people into precarious living arrangements. A banjiha is one type of substandard housing with a monthly rent of around $450 for what is often less than a few hundred square feet of space. It is but one of the three most common, cramped, and cheap forms of housing, the other two being gosiwon (dorm-sized apartment residences) and oktapbang (rooftop rooms). While South Korean film and television often display the glamorous highrises that saturate the hypermodern Seoul skyline, many young hopefuls looking to prosper in the nation’s capital inevitably fall short of achieving this fantasy. Although there is no quick fix to Korea’s widespread inequity, the government should investigate an array of creative solutions focused on broadening the availability of viable housing options, expanding the pathway to home ownership, and increasing the availability of public housing options.

The housing crisis of Korea’s precarious youth represents a broader trend of Korean urban inequality, exacerbated by neoliberal free-market reforms at the turn of the millennium. What’s more, the development of the nation’s economy has its foundation in what is considered Korea’s greatest national dishonor: its annexation by Japan in 1910 and the 35 years of colonial rule that ensued. During this time, Japan instituted a strong central bureaucracy that overwhelmingly industrialized South Korea.

In the decades following the end of Korea’s occupation, the country experienced a period of rapid economic growth. The government instituted a series of reforms similar to those the Japanese implemented under colonial rule: robust industrial, educational, and economic programs under authoritarian control. Yet, when Korea’s foreign exchange reserves were depleted in the late 1990s, the country’s impressive growth came to a halt, and South Korea neared bankruptcy. As the International Monetary Fund stepped in to stabilize the economy, Korea was forced to implement high interest rates and restructure its economic policy around neoliberal standards.

Those who came of age during Korea’s economic downturn were especially affected, particularly in terms of urban inequality, job insecurity, and housing uncertainty. The crisis brought about a decline in full-time and lifelong employment, reductions in social services, and heightened social stratification. Many young people who migrated to the Seoul metropolitan area seeking better education and employment opportunities continue to find themselves cyclically trapped in low-wage, unstable, and precarious jobs with limited housing options.

Today, Seoul boasts some of the world’s highest speeds of internet connectivity. But despite the city’s robust technological and innovative industrial advancements, over 30 percent of South Korea’s young adult population lives in poverty. The country’s birth rate is stagnant, and over 40 percent of households consist of one person, indicating that much of the country’s youth is choosing not to marry or start a family. Many remain single due to rampant financial insecurity, which inhibits them from being able to afford better housing because high rents are often out-of-reach for single-income households. Gosiwon specifically cater to singles and prevent them from starting a family—trapping them in a cycle of poverty.

The consequences of these constricted living conditions for the mental and physical well-being of residents are catastrophic. A 2021 Seoul National University (SNU) study shed light on this reality. The researchers highlighted that rates of anxiety were alarmingly high among residents, with many primarily concerned about their inability to pay rent, housing cost increases, and deposit refundability. Additionally, the coronavirus pandemic, which was particularly harsh in South Korea, magnified these anxieties. Those forced to isolate in their tiny abodes faced high levels of social isolation and disconnection from friends and loved ones, worsening their mental health.

The physical health of these residents is often similarly abysmal. With improper ventilation, limited living space, and squalid sanitary conditions, many participants in the SNU study reported feeling lethargic and being in poor physical condition; even so, they could not afford the basic healthcare necessary to overcome such detriments. Since gosiwon also lack kitchen space, many residents are unable to store or cook healthy food options and struggle with food insecurity. Clearly, Korea’s urban youth not only lack sufficient living space, but their spatial arrangements also beget an array of concerning implications for their health and prosperity.

As housing prices in Seoul continue to rise, the patience of South Korea’s youngest bloc of voters dwindles.

As housing prices in Seoul continue to rise, the patience of South Korea’s youngest bloc of voters dwindles. Young adults are utterly outraged by the lack of government intervention concerning their precarious outlook. In a way that is unprecedented among previous generations, these voters are less concerned with security issues, like the threat of North Korea. Instead, at the polls, housing continues to influence the ballot decisions of young South Koreans. In a statement to The New York Times, professor and elections expert Kim Hyung-joon stated, “To [young South Koreans], nothing matters as much as fairness and equal opportunity and which candidate will provide it.”

This issue has not been left undiscussed by some of Korea’s most prominent politicians. Seoul’s own mayor, Oh Se-hoon, has promised to make the capital a “city of hope,” acknowledging in a press interview that housing inequality is “perhaps the biggest grievance of young people in Korea.” Campaign promises like those of Mayor Oh, however, may remain unrealized, and it is unclear whether or not government leaders will take adequate action to improve housing conditions for the urban youth of South Korea.

Recently, the Seoul city legislature approved substantial subsidies to aid the city’s low-income youth, which will allow quality housing to be rented at a much lower cost than market value. These subsidies, however, do nothing to solve the sheer shortage of affordable housing. Once they expire, young Seoulites without stable employment will again be left unable to afford rent prices. Thus, approaches aimed at expanding the stock of affordable housing options and facilitating home ownership offer the most assurance of long-term relief. The city is planning to build 55,000 new public housing units by 2025; however, with nearly 471,000 of Seoul’s youth population already living in public housing, it is likely that more will be needed.

If politicians fail to advance adequate housing options, equal opportunity surely cannot be achieved. The current outcry, though, offers hope that housing inequalities will be addressed in the future. Still, given the scale of the inequity, it is obvious there exists no blanket solution. While the Seoul city government has already begun providing assistance, additional measures are necessary to ensure that residents living in banjiha, gosiwon, and other substandard living arrangements can afford healthcare, build families, and become upwardly mobile. If South Korea forsakes its urban youth, adequate housing—let alone the Parks’ lavish mansion—will remain just another unrealized fantasy.