When the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan in 2021, Central Asian governments continued with business as usual. After 20 years of an internationally backed government in Afghanistan, the five Central Asian nations (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan) have become accustomed to shared trade and infrastructure and sought to maintain this regional security following the Taliban’s return to power. This approach has benefited both these states and the Taliban, with Central Asian nations meeting regional security and trade goals while Afghanistan receives electricity, food, and humanitarian aid. However, this stability is threatened by an issue that has plagued Central Asia for decades: water.

In March 2022, the Taliban-led government began digging the Qosh Tepa canal, a proposed 285-kilometer canal intended to irrigate 550,000 hectares of agricultural fields in northern Afghanistan. While this waterway would help alleviate Afghanistan’s chronic food insecurity, its construction could pose both internal issues for Afghanistan and external economic, political, and environmental issues for its northern neighbors, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

Central Asia has a long history of water disputes and concerns. Spurred on by dreams of collectivization and large-scale socialist industrial undertakings, the Soviet government set out on an ambitious project in 1959 to turn Central Asia into its primary cotton supplier. In order to grow this water-intensive crop in the arid Central Asian steppe, the Soviet government irrigated the region through canals and dams stemming from the Aral Sea and the two major rivers that flowed into it. The project was unsustainable and inefficient: Significant amounts of water leaked or overflowed, with the large Karakum canal in Turkmenistan reportedly wasting 30 to 70 percent of its water. As a result, the Aral Sea, which was once the world’s fourth largest lake, shrank by 60 percent from 1960 to 1998. By the 2010s, the sea had almost completely disappeared.

While the Soviet project ultimately did help create a wildly successful cotton industry, it set a precedent for irresponsible water usage practices in the region. Without the Aral Sea, the five Central Asian countries were left to rely on water from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. When the Soviet Union collapsed, ownership over what was once shared water infrastructure became murky and necessitated collaborative decision-making, as each state’s water usage decisions affected the others.

The water situation today is dire. The governments of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan have all publicly commented on their own water crises, attributing low water levels and mass water waste to regional mismanagement and climate change. These tensions have already caused security issues in the region. Disputes over a water supply station in Tajik-Kyrgyz resulted in border skirmishes responsible for at least 100 deaths in 2021 and 2022. In May 2023, Iranian and Afghan border guards clashed over rights to the Helmand River, leaving three dead.

Now, with the return of the Taliban, Central Asia is facing yet another water-related conflict as Afghanistan digs the Qosh Tepa canal. The canal is intended to draw water from the Amu Darya River, which flows along Afghanistan’s northern border with Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. The canal is projected to divert 10 billion cubic meters of water from the already waning Amu Darya each year. Critically, the water from the Amu Darya supplies Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan with 80 percent of their water resources, the majority of which goes toward irrigation.

The economic effects of the diversion will be felt most strongly in Uzbekistan, where cotton production makes up 17 percent of national GDP and 40 percent of jobs. It would also disproportionately affect the southern regions of Bukhara, Khorzem, and Karakalpakstan, risking intensified conflict in an area that already experienced violent unrest in July of last year. In Turkmenistan, the population depends on the Karakum Canal (and therefore the Amu Darya River) for drinking water in its particularly arid environment. The Amu Darya, whose water levels have decreased by one-third in some areas of Turkmenistan, also feeds a water-intensive agricultural sector. Agriculture (mostly cotton) accounts for 11 percent of Turkmenistan’s GDP and uses a whopping 91 percent of the country’s water resources. Even experts in Kazakhstan (which does not border Afghanistan or the Amu Darya River) are concerned about the construction of Qosh Tepa, as it would result in more water being drawn from the Syr Darya, the other major river in Central Asia that supplies Kazakhstan with the majority of its water.

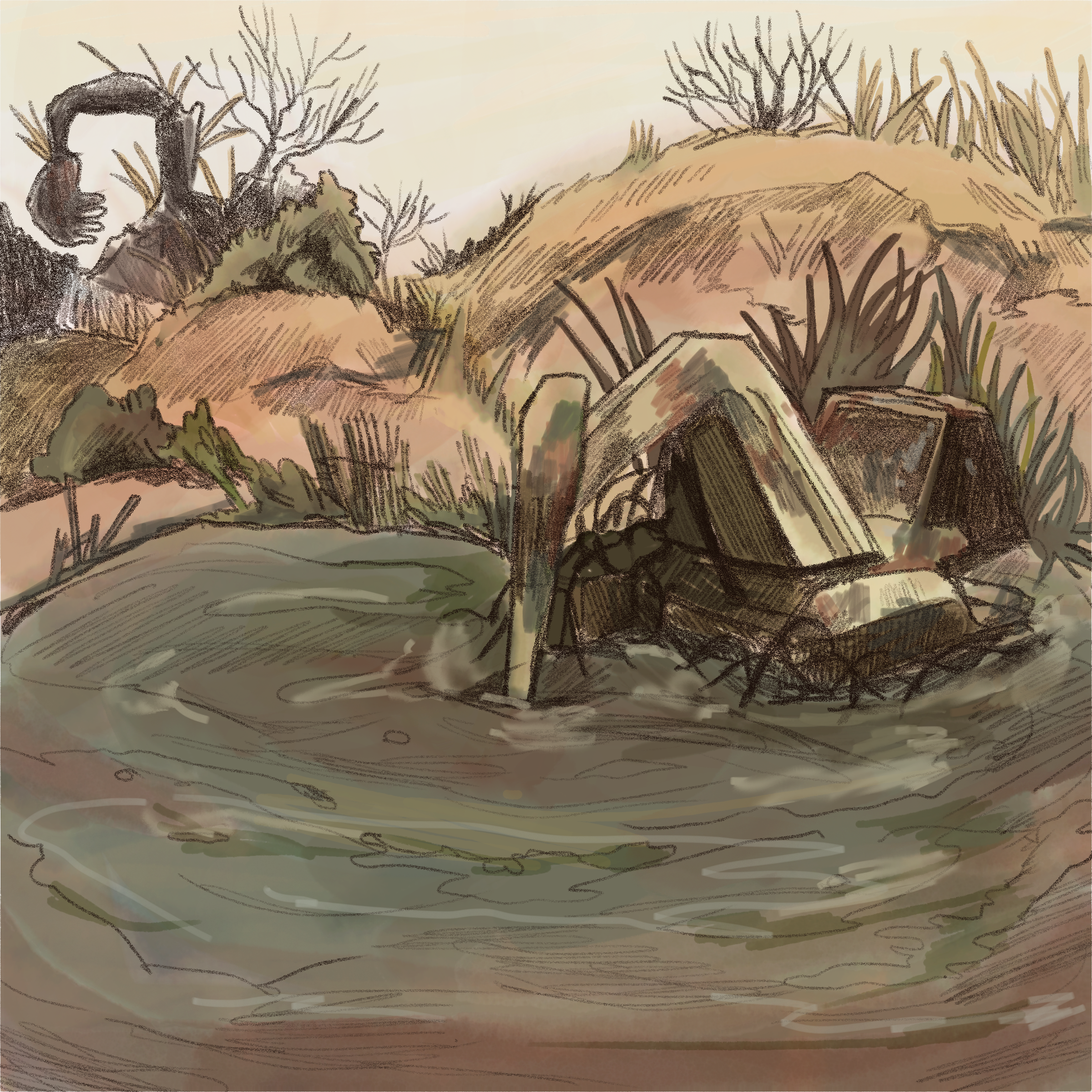

The proposed Qosh Tepa canal’s impact in Afghanistan has also been debated. While it is projected to help the 15 million Afghans facing chronic food insecurity and create an estimated 250,000 jobs, the canal’s construction will most likely have unintended environmental consequences. So far, Qosh Tepa’s first 108 kilometers lack reinforcement in its banks and bottom, meaning it will likely waste a large proportion of its water. Satellite imagery of a Qosh Tepa diversion dam has already shown signs of overflow and erosion. There is also the question of funding, as billions of dollars worth of funds in Afghanistan’s central bank were frozen after the Taliban returned to power. For a project that will cost somewhere around $700 million, a shortage of cash could seriously impact construction quality.

Under international law, Afghanistan does have the right to claim Amu Darya’s water. However, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan allocated the canal’s water among themselves in the Almaty Agreement in 1992, taking up old Soviet quotas. They continue to operate accordingly. Due to the Afghan War and Afghanistan’s lack of Soviet-era ties to Central Asia, Afghanistan was excluded from the Almaty Agreement under the assumption that it would use little of the Amu Darya’s water.

As the construction of the Qosh Tepa Canal marches on, Afghanistan and Central Asia face a major diplomatic test. Although the Taliban is not exactly used to diplomatic solutions, both they and the governments of Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have expressed a desire to solve this issue amicably. In March 2023, an Uzbek delegation visited Afghanistan to discuss improved cooperation across a variety of issues. No resolution was officially reached, with the Taliban simply claiming that “Uzbekistan is ready to cooperate with the Islamic Emirate in completing the Qosh Tepa Canal project.” The Uzbek Ministry of Foreign Affairs was even less committal, releasing a statement on their website that did not even mention Qosh Tepa, only stating that “special attention” had been paid to “cooperation in the water and energy sectors.” While this lack of resolution is discouraging, another Uzbek delegation is expected to continue negotiations with the Taliban before the end of 2023. Even the president of Uzbekistan, Shavkat Mirziyoev, mentioned Qosh Tepa in a September 2023 presidential address, asserting that it is “necessary to conduct practical talks on the construction of a new canal in the Amu Darya basin.”

Still, it is not clear whether diplomatic efforts will be able to cool the tensions brewing in the region, with some Afghan leaders alluding to the possibility of a military confrontation. Afghan news outlet Tolonews quoted Defense Minister Mawlawi Mohammad Yaqoob Mujahid as saying, “All of us, especially the national and Islamic armies of the Defense Ministry, are behind the implementation of such projects, and they will support it with all their power.” Sirajuddin Haqqani, the current Minister of Interior Affairs, was cited saying that Afghans are ready to “defend their rights.”

Both the Central Asian countries and Afghanistan are faced with a difficult choice. Afghanistan risks isolation from critical allies and trade partners if it oversteps with the construction of Qosh Tepa, but it also cannot sustainably continue relying on external aid to feed its starving populace. Central Asian countries, particularly Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, risk the loss of their lucrative cotton industries, which would cause high levels of unemployment and potentially country-wide destabilization. The alternative, however, is stopping the construction of Qosh Tepa through negotiation with a notoriously stubborn southern neighbor, or, if that fails, via military engagement, which could lead to even greater regional instability. As climate change looms large and a history of water mismanagement catches up with the region, the construction of the Qosh Tepa Canal will force governments to create new legal frameworks that bring Afghanistan into the fold or risk regional unrest.