Even as the national Republican Party nurtures a strong sect of climate denialists, Republican-dominated Southeastern states have been quietly courting the electric vehicle (EV) market. It is a daunting task considering increased polarization around climate change, but state parties have found ways to thread the bipartisan line and deliver for their states’ economies. Brian Kemp, the Republican Governor of Georgia, has said, “I’m fulfilling my promise of creating good-paying jobs for our state…You’re gonna have a lot of Republicans driving [Ford’s electric pickup].”

These red states are not only taking the lead on traditionally “blue” policies but also using legislation championed by the Biden administration to do it. Mississippi and Alabama—two of the most conservative states in the Union—are among the many states using federal legislation to deliver on economic promises. Mississippi is creating jobs by taking advantage of $216 billion in corporate tax subsidies from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Localities in Alabama are improving public transportation to increase the workforce participation rate through some of the $196 billion from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill. Now, this does not mean these states will be voting for Biden this November. Still, this development represents both an interesting exception to stolid partisan politics and a potentially bipartisan shift on EVs and clean energy going forward.

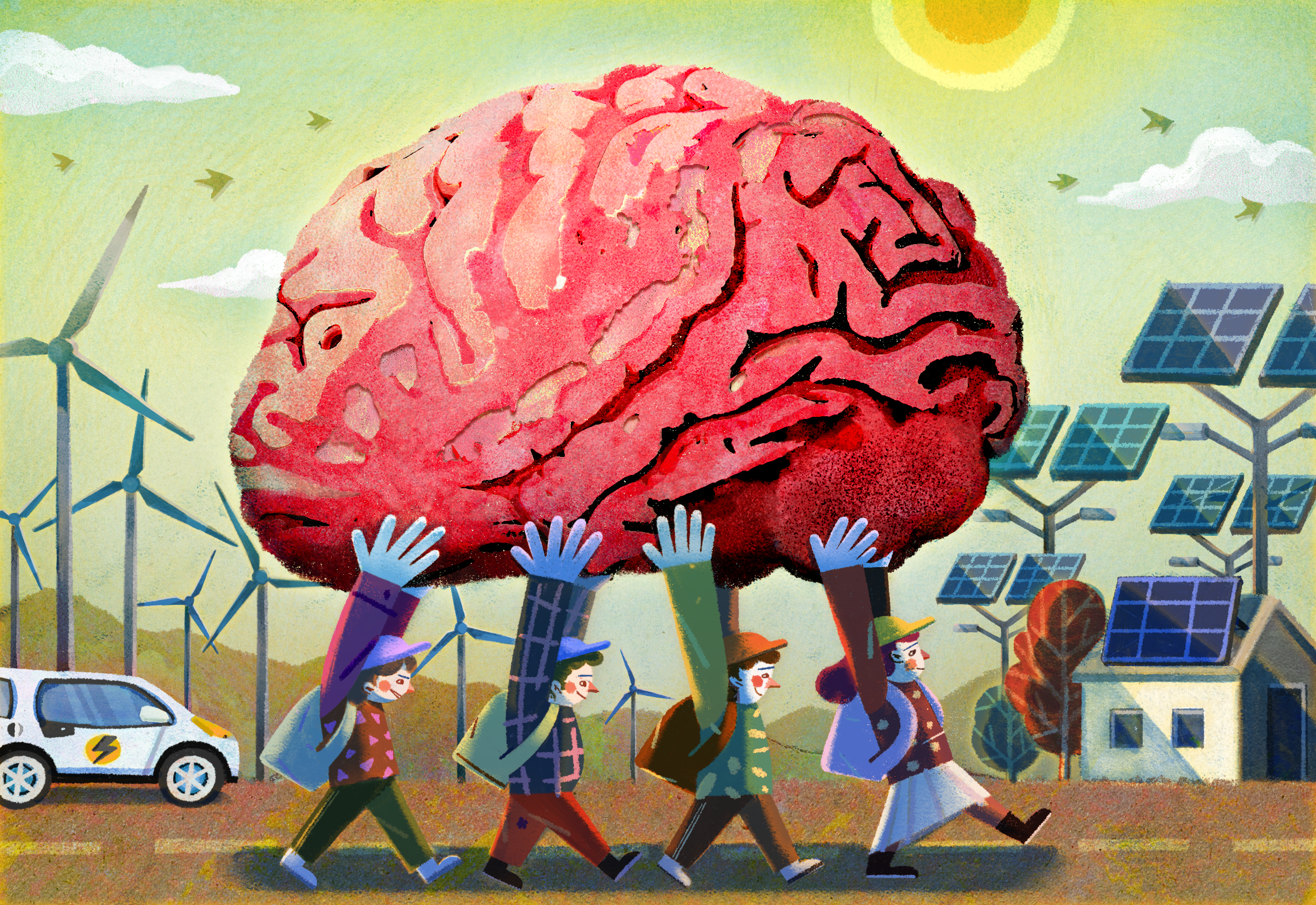

In his reelection speech, Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves promised to tackle “brain drain,” stating, “For too many decades our most valuable export has not been our cotton, or even our culture, but our children.” From 2020 to 2022, Mississippi and Louisiana were the only Southern states to see a net population loss. Many movers left for better opportunities in neighboring states, which is why Reeves was focusing on job growth by making Mississippi “masters of all energy.” This sentiment directly contradicts his own reelection campaign last year, which was openly critical of green investment, decrying his opponent’s donors as “solar panel buddies…that have tried to run the oil business out of America.” He may have needed to say that to win the Mississippi gubernatorial race, but his actions in office have spoken louder than his words.

Reeves, assisted by US Senator Roger Wicker (R-MS), has overseen the largest workforce investments in Mississippi history thanks to the IRA. The IRA includes tax incentives at every step of the manufacturing and sale of EVs, creating an “American manufacturing renaissance.” It also provides major incentives for clean energy production, having created over 100,000 clean energy jobs in its first six months. Reeves, with Republican supermajorities in the state legislature, has pushed through millions of state dollars to further incentivize businesses to take advantage of the IRA. In Marshall County, for instance, four companies are investing $1.9 billion in an EV battery plant. In Lowndes County, Steel Dynamics is investing $2.5 billion in an aluminum mill (EVs require 40 percent more aluminum than other vehicles) and a biocarbon facility to reduce emissions. In Madison County, Amazon is investing $10 billion in new data centers powered by new solar farms.

Initially skeptical of clean energy’s prospects, Reeves appears to have embraced its good-paying jobs—workers in the clean energy industry can expect to make about $20,000 more than the state average. It is not just Reeves: The Mississippi legislature voted almost unanimously across party lines for the state money to bring these businesses in. The clear movement of the executive and legislative branches to take advantage of federal largesse will be felt in Mississippi for generations. With the help of the Biden administration, Reeves is putting the state on a path to lead the EV and clean energy transition, attract future investment, and retain talented workers. With some luck, Mississippi may be as attractive as its twin flame, Alabama.

Alabama has, as Governor Kay Ivey quips, “a good problem to have.” Job growth in the Cotton State has been so great that positions are going unfilled. With one of the lowest unemployment rates in the nation, almost everyone looking for work can find it. Many jobs are being created through the EV industry and, by proxy, the IRA. The nation’s first graphite processing plant, which will produce a form of graphite essential to EV batteries, broke ground southeast of Birmingham in April 2022. From there, the graphite will be sent to a new battery factory in Montgomery and eventually to a recycling facility in Tuscaloosa. Despite this growth, many Alabamians are not looking for work. The workforce participation rate, one of the lowest in the nation (10 percent below the national average), remains a real problem. Federal legislation can also aid in mitigating this issue—but in Alabama, cities, not the state, are taking the lead to find solutions.

Alabama Lieutenant Governor Will Ainsworth’s “Alabama Workforce Development Plan” cites transportation as a key barrier to workforce participation—“15% of participants have lost or quit a job due to transportation issues.” Despite state recognition, 82 Alabama organizations that asked Governor Ivey to prioritize transportation were ignored. As one of only three states that do not fund public transportation, the $154 million that Alabama has received from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill has meant that much more. In Birmingham, a $12 million grant allowed the city to repair, expand, and lower the emissions of its bus fleet. In Huntsville, a $20 million grant is being used to expand bicycling and walking pathways. In Alabama’s case, inaction on the part of the state government has pushed localities to achieve solutions.

Defying climate denialism, Mississippi and Alabama are joining the economic boom of the Battery Belt. Green subsidies (that their congressional representatives often voted against) are blurring partisan lines and empowering the Southern economy. Though it is unclear how long this modern “Era of Good Feelings” around green investment lasts, anything is possible. The new industries will dramatically change these states; we may not recognize them in a decade or two. Mississippi and Alabama found an unlikely ally in the Biden administration, and both states’ economies are looking brighter as a result. For Mississippi and Alabama, at a time of hyper-partisanship and polarization, a localized break from national politics is opening up the space for meaningful political progress.