2023 was the year of unions. The 148-day strike led by the Writers Guild of America ended with a 5 percent wage increase in the first year, bonuses for movies and TV shows on streaming, and protections against AI usage. Shortly after, the Screen Actors Guild – American Federation of Television and Radio Artists strike led to a 7 percent wage increase in the first year and similar increases in bonuses and AI protections. In the auto industry, the United Auto Workers strike successfully secured raises of at least 33 percent and a three-year wage progression to the top pay rate, a marked improvement from the previous eight-year wage progression.

And yet, as conversations about unions become more frequent, union membership rates are dropping, a phenomenon aptly named the “union paradox.” 59 percent of workers across all sectors support unionization in their workplace, but the union membership rate in 2022 was only 10.1 percent, the lowest on record. A combination of policies and companies has created several obstacles for employees to have a union to join in the first place. The Economic Policy Institute estimates that corporations spend $431 million annually on union-avoidance consultants, shutting down unions before they can even form. Increasing automation is making it easier for companies to replace their employees with technology, and a slew of legislation has hindered effective union organization. One type of legislation in particular has found a home in national headlines: right-to-work laws.

Simply put, right-to-work (RTW) legislation prohibits requirements that employees in a unionized workplace be required to join a union to retain their positions. These laws—which date back to 1944 in the United States—have seen a resurgence in recent years. Since 2012, six states have enacted RTW laws: Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Missouri (though Missouri overturned its RTW legislation in 2018). Proponents argue that employees should be able to decide whether they want to be part of a union and emphasize the economic benefits of RTW laws, such as job growth. Opponents often use a simple yet effective counter-argument: They weaken unions. Few, however, treat RTW laws with the nuance they deserve.

By weakening unions, RTW legislation may hurt workers. In 2023, union members earned 18 percent more than non-union workers. The presence of unions can also combat income inequality; in the United States, public sector unions engendered a 16.2 percent reduction in wage inequality for men and 10.7 percent for women. Perhaps most crucially, increasing the presence of unions leads to greater safety in working conditions. A 2019 study of over 37,000 Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) inspections in the construction industry found that union worksites were 19 percent less likely to have an OSHA violation than non-union worksites.

In states with RTW laws, fewer employees become due-paying members of unions, diminishing their financial standing and bargaining power. These numbers significantly impact unions in these states and—most importantly—their employees. In Michigan, RTW laws cost unions more than $50 million annually in lost dues. In Wisconsin, labor leaders report that RTW laws, alongside the repeal of prevailing wage laws, have decreased wages for construction workers while increasing pay for their bosses.

In a study on five states—Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, West Virginia, and Kentucky—from 2011 to 2017, RTW laws were found to be associated with a drop of approximately 4 percentage points in unionization rates and a wage drop of about 1 percent five years after adoption. These effects are especially observed in three union-driven industries: construction, education, and public administration. In these industries, also five years after adoption, RTW laws reduced unionization by almost 13 percentage points and wages by over 4 percent.

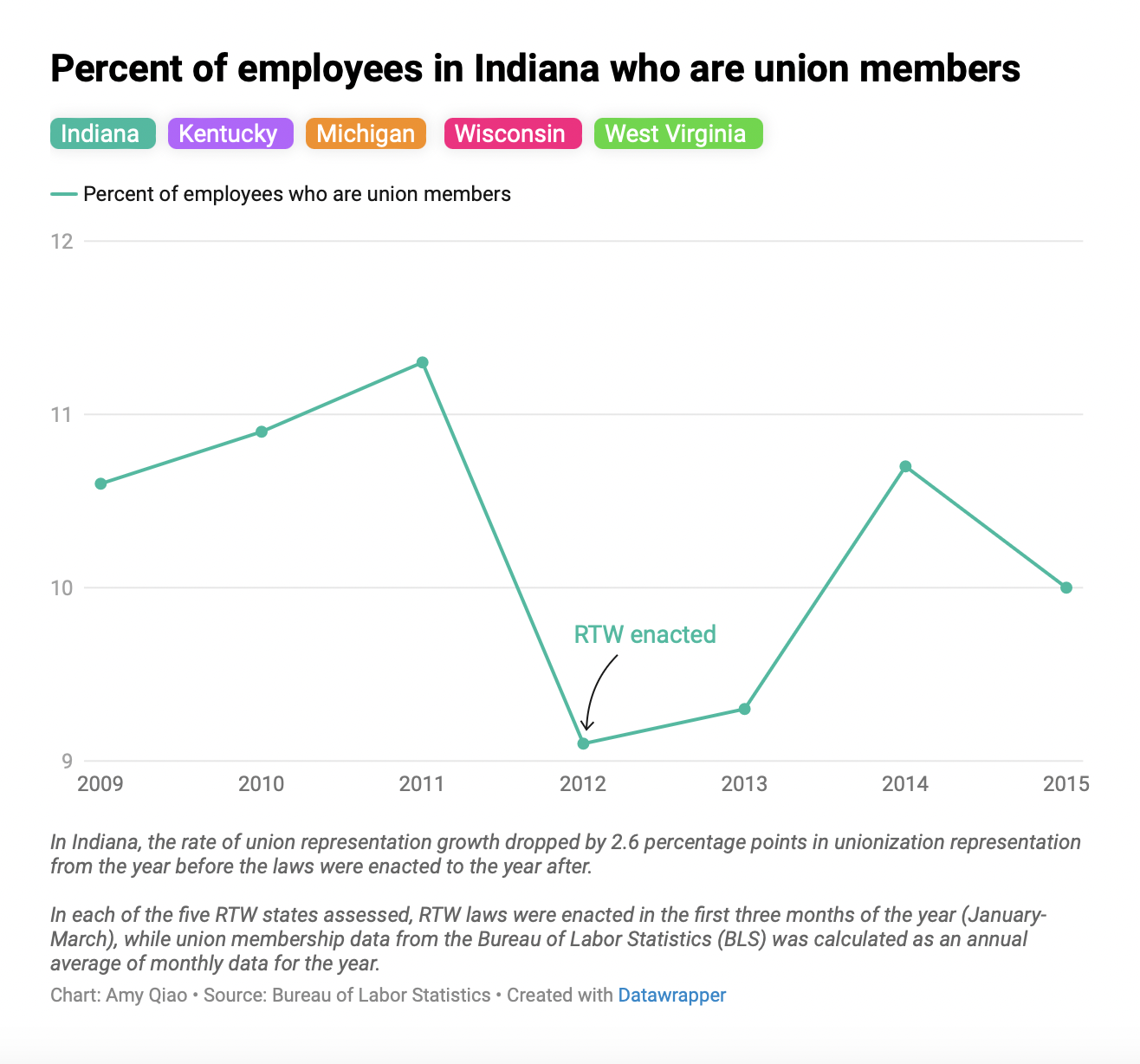

Likewise, when looking at data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, it is evident that union membership decreases after RTW laws are enacted. In each of the five states, the rate of union representation growth dropped compared to the year before the laws were enacted.

While RTW laws obstruct union membership and representation, this is not the full picture; those in favor stress the economic and employment growth associated with passing RTW legislation. Comparing border pairs, or two bordering counties in states with different RTW policies, one study reported a 28 percent increase in manufacturing employment in RTW counties compared to their neighboring non-RTW counties. The same study observed that the employment-to-population ratio was 3.51 percentage points higher in RTW counties than in non-RTW counties when measured by workplace location. The study’s authors attribute these differences to the increase in desirability for businesses to operate in RTW states compared to non-RTW states. From this, corporations are driven to create more jobs and offer more competitive wages in RTW states.

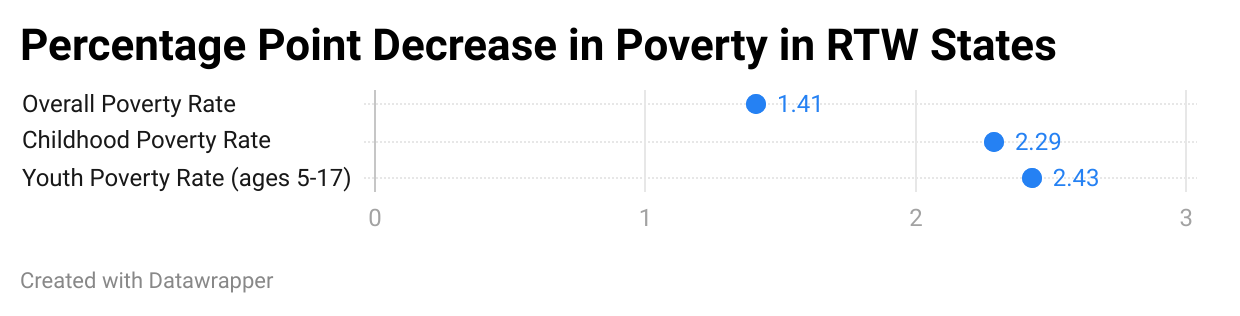

Most notably, in RTW counties, the overall poverty rate was 1.41 percentage points lower than in non-RTW counties, likely as a result of increased job opportunities and higher employment rates. RTW states also saw a 2.29 percentage point decrease in childhood poverty rates and a 2.43 percentage point decrease in youth (ages five to 17) poverty rates.

Although the debate around RTW laws seems to have two distinct and definitive arguments, the answer is far more complex. Those in favor of RTW laws emphasize the economic benefits while those against stress the role of unions in protecting workers’ rights. But these should not be distinctly opposing arguments. You can be pro-union and still recognize that RTW laws induce an economic incentive for businesses to create jobs in a state. You can be pro-business and agree that RTW laws interfere with union membership and effectiveness. In the labor rights discussion and beyond, you can both be right.

This point is precisely encapsulated in a 2019 study examining the outcomes of RTW laws in Wisconsin, which found a small but significant reduction in wages in tandem with an increase in employment in the year RTW laws were enacted. While RTW laws impair unions’ effectiveness, RTW states may attract businesses, leading to increased employment opportunities and diminished poverty rates.

As more states continue to enact—and repeal—RTW laws, it is clear that the discussion around RTW legislation is not going anywhere. In these conversations, the dual effects of RTW cannot be ignored. The trade-off between employee protection and employment options must be carefully considered by compiling and studying additional data. We can turn to states that have incentivized businesses without hindering unions to see if it is possible for these two goals to intersect. We can look at ways to increase union effectiveness in states where, RTW in place or not, unions are being hampered. We can look at ways to encourage businesses to create jobs in states that support unions, through policy and beyond. As the fight for the future of labor rights continues, we must not accept or dismiss any law too quickly—because there is always more to the picture.

The change in the rate of union representation growth was determined using the difference-in-difference (DID) method which can be calculated with the following equation:

difference_in_difference = (post_treatment – pre_treatment) – (post_control – pre_control)

DID measures the causal effect of an event by comparing the difference in outcome when the event happened to when it did not. For example, in the year before RTW laws were enacted in Indiana, union representation grew by 0.4 percentage points, while in the year of enactment, union representation dropped 2.2 percentage points, leading to a difference-in-difference of -2.6 percentage points following the enactment of RTW laws in Indiana.